Losing the Central Valley’s last, best spring Chinook run isn’t an option. So we’re getting to work.

High up in the western slopes of the Sierra Nevadas, one small tributary is a bright spot for California salmon.

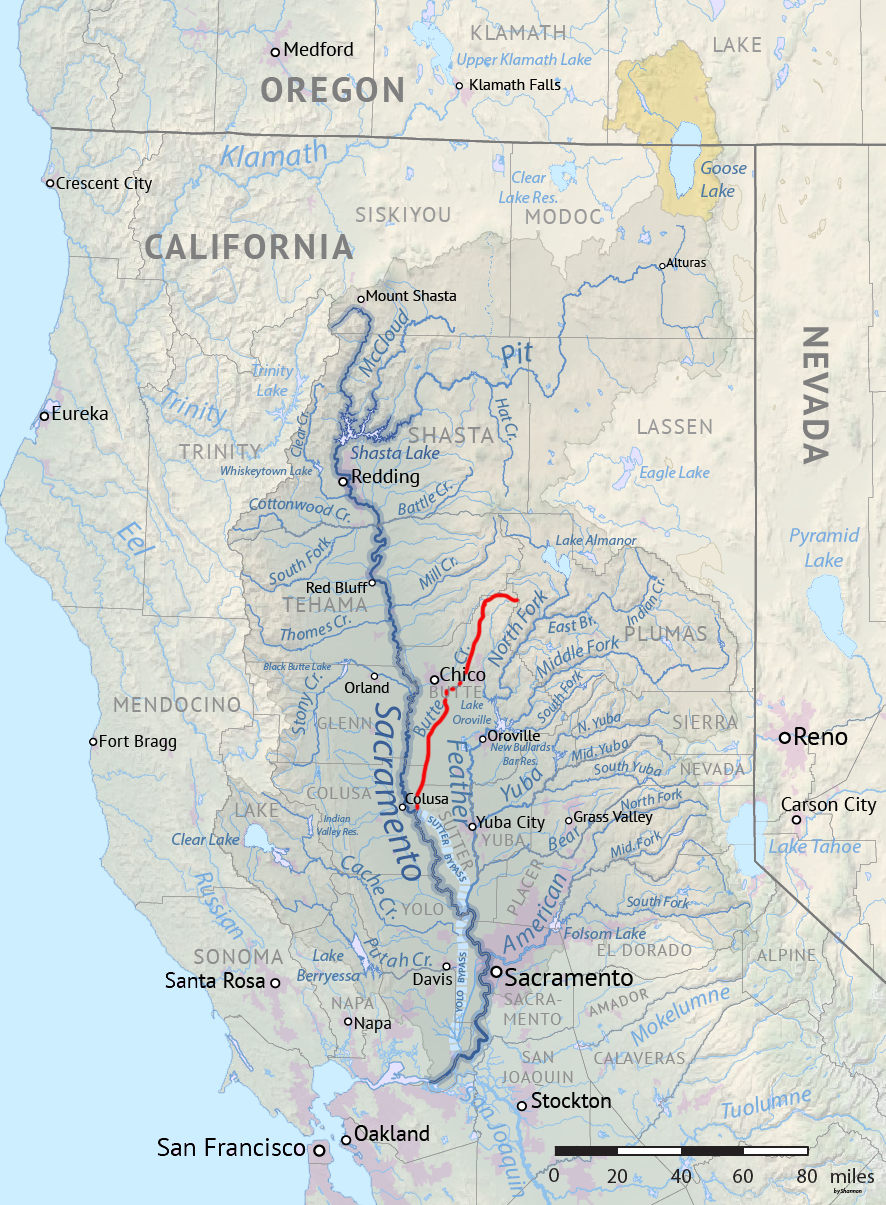

From headwaters in Lassen National Forest, Butte Creek runs some 110 miles southwest through steep canyons and farmland to its confluence with the Sacramento River near Colusa, in California’s Central Valley. A slender thread for much of its length, Butte Creek nevertheless boasts wild spring Chinook runs that rival much larger rivers like Oregon’s Rogue.

“Butte Creek spring Chinook are the reason why Sacramento springers overall aren’t yet considered to be fully endangered under the Endangered Species Act, only threatened,” says Wild Salmon Center Senior Manager John Kober. “We all should be paying attention to this special salmon run.”

“Butte Creek spring Chinook are the reason why Sacramento springers aren’t yet considered to be fully endangered. We all should be paying attention to this special salmon run.”

WSC Senior Manager John Kober

In recent decades, Butte Creek springers have proven to be surprisingly resilient: rebounding from heat waves, disease outbreaks, warm water, and water management mishaps. Meanwhile, other Central Valley wild spring Chinook populations have all but disappeared.

The decline of Central Valley salmon has many analogues: natural resource extraction and human development have changed, dammed, and degraded countless salmon and steelhead rivers up and down the West Coast.

But the story of California’s Central Valley is particularly dramatic. A century ago, the rivers of this vast drainage may have seen spring Chinook runs as large as 700,000 fish. In recent decades, good years rarely top 30,000 across the entire valley. And many of these fish are headed to Butte Creek. In some recent years, nearly 15,000 spring Chinook have reached spawning grounds in Butte Creek—though these numbers fluctuate widely.

Why Butte Creek? Kober says scientists are still studying the secrets of this erratic standout. But in a region where most salmon streams were beheaded by dams decades ago, Butte Creek’s own dams—collectively, the PG&E DeSabla-Centerville hydroelectric project—are now managed to release cold water in summer to an 11-mile downstream stretch of habitat utilized by holding and spawning adult salmon. Lower Butte Creek, meanwhile, represents some of the Central Valley’s last functional rearing habitat: refugia where juvenile spring Chinook can bulk up to better their odds of surviving their perilous journey to the ocean.

But given the volatility of the Central Valley’s last, best spring Chinook run, Kober says that banking on comparatively good conditions isn’t enough to keep Butte Creek’s springers protected.

“What we need is a long-term plan for Butte Creek,” he says. “Because losing the Central Valley’s one remaining healthy spring Chinook run isn’t an option.”

With this urgency in mind, WSC helped to launch a partnership in 2022 with local conservation partner Friends of Butte Creek and a growing list of allies including CalTrout, American Whitewater, the California Sportfishing Protection Alliance, and the Mechoopda Indian Tribe. With Kober coordinating, the partners are now crafting a comprehensive plan to ensure Butte Creek’s health for decades to come.

“What we need is a long-term plan for Butte Creek. Because losing the Central Valley’s one remaining healthy spring Chinook run isn’t an option.”

WSC Senior Manager John Kober

It’s an approach modeled on a series of WSC-led strategic action plans for salmon watersheds across coastal Oregon. These plans—four and counting—have drawn praise from federal agencies like NOAA for laying out clear, science-driven restoration strategies and leveraging funds for locally-led projects.

For a Butte Creek plan, the partners will focus on three main goals: improving fish passage, maintaining sufficient water quantity during fish migrations, and restoring habitat, particularly in the creek’s agricultural lowlands. By necessity, Kober says the plan will diverge from its Oregon counterparts in a few ways: most notably in factoring in the need for ongoing human intervention.

“Within California, Butte Creek is absolutely a stronghold in some years,” Kober says. “But the reality is that any effective plan for Butte Creek salmon must go beyond habitat restoration.”

Kober points to the heavy human handprint already on Butte Creek: three dams and multiple canals from the Feather River and other water sources. Sometimes, this infrastructure can prove helpful: providing cold water in summer, maintaining fish-friendly stream flow. But it can also be a liability. In 2019, insufficient water releases from the Centerville project led to the deaths of 20,000 spring Chinook holding below: nearly the entirety of that year’s spawners.

“One day, dam removal could be on the table for Butte Creek,” Kober says. “But until then, we must find ways for this infrastructure to not only avoid harming but actively help its spring Chinook.”

In the year to come, WSC and our partners will dig into that work. And with your help, we hope to bring to light the secrets of Butte Creek—so it can continue to sustain wild springers in the heart of California.

“One day, dam removal could be on the table for Butte Creek. Until then, we must find ways for this infrastructure to not only avoid harming but actively help its spring Chinook.”

WSC Senior Manager John Kober