A rare kind of coastal habitat could help Oregon build resilience for fish, flooding, and local communities.

Maybe you’ve heard about the mangroves of Florida, Jamaica, and Indonesia: gnarled, hardy tropical trees that thrive in salty tidal waters.

Mangrove swamps are prized for their carbon-storing superpowers—spurring international calls to protect them—as well as for the cool, shady refuge they create for fish and wildlife species.

“A lot of people know about mangrove swamps,” says Cyndi Curtis, Wild Salmon Center Oregon North Coast Manager. “But not so many know about Sitka spruce swamps—another forested wetland that’s totally unique to the Pacific Northwest.

Like mangroves, Curtis says, Sitka spruce swamps can sequester massive amounts of carbon, and also act as important storm surge buffers for lowland communities. A century ago, these tidal spruce swamps hugged estuaries and rivers up and down the Oregon coast. Today, just a few remnant forests remain—and vanishingly few larger than 20 acres.

A century ago, tidal spruce swamps hugged estuaries and rivers up and down the Oregon coast. Today, just a few remnant forests remain—and vanishingly few larger than 20 acres.

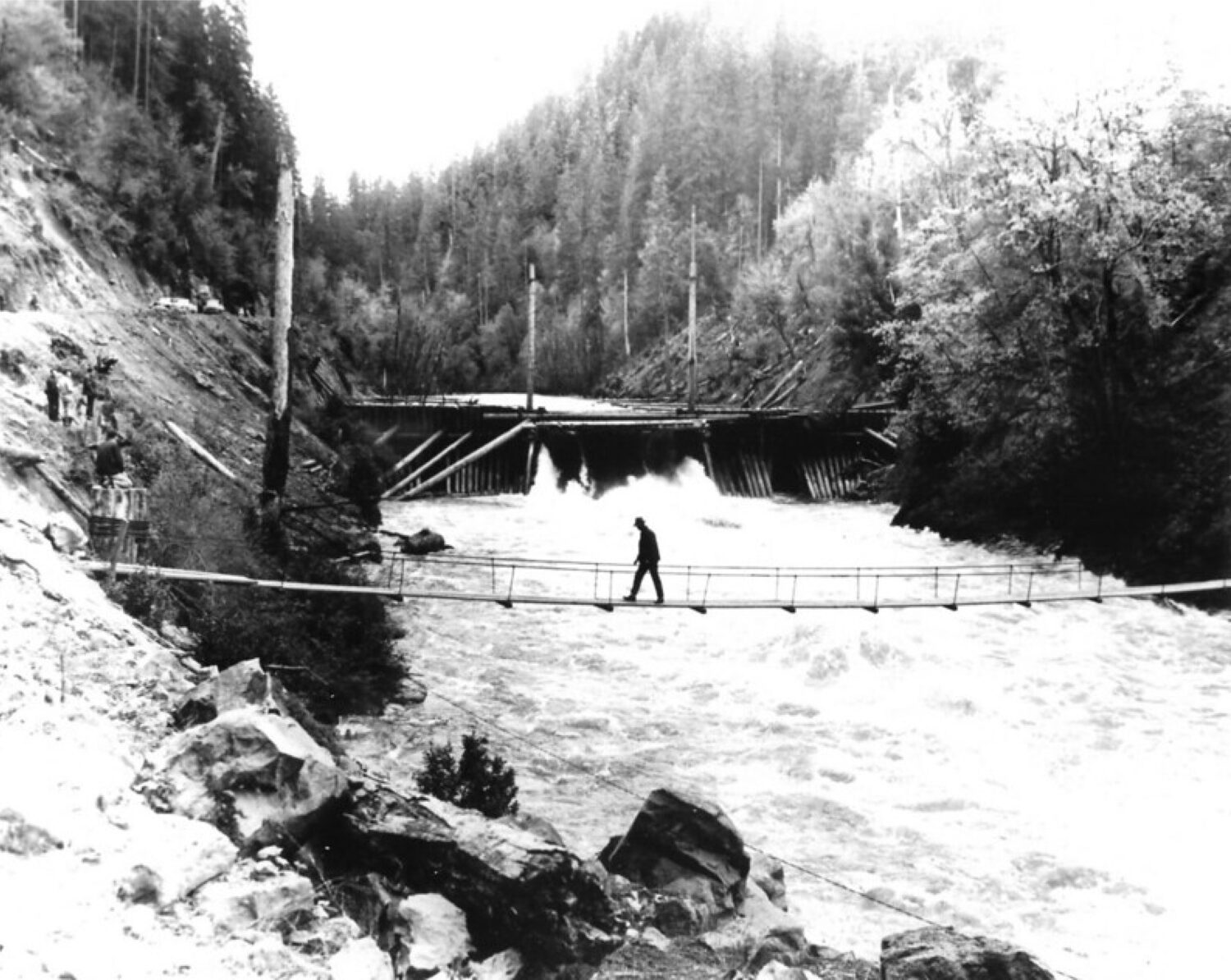

The disappearance of Oregon’s spruce swamps stems from two practices brought by white settlers—both of which made life much harder for juvenile salmon. In the early 20th century, timber drives sent massive logs barreling down rivers to sawmills, scouring any bankside trees left unlogged, along with mainstem habitat for wild fish. Then, these cleared coastal lowlands were diked and drained—converting marshes and wetlands into pasture and cropland, and eliminating key salmon nurseries in the process.

“The irony is that diking to create agricultural lands actually blocked sediment inputs from winter floods,” Curtis says. “And regular flooding was what brought in the nutrients and sediment that made these lands rich. Now, many of these diked lowland areas are actually subpar for farming, and some are even sinking.”

Private owners still hold the vast majority of land that once nurtured Oregon’s spruce swamps. But today, some are starting to explore alternate uses for these unproductive lands, including tidal reconnection. For Curtis, it’s an opening—to bring back the Sitka swamp for threatened species like Oregon Coast coho, and also for coastal communities facing an increasingly swampy future.

It’s an opening—to bring back the Sitka swamp for threatened species like Oregon Coast coho, and also for coastal communities facing an increasingly swampy future.

On a perfect sunny June afternoon, Curtis navigated a kayak into the log-jammed mouth of Coal Creek. The creek, which meets the Nehalem River just a few miles from the bay, is tidally-influenced—but high enough in the system for a special balance of freshwater and saltwater.

“There’s a sweet spot for Sitka spruce swamps,” Curtis explains. “They need the tidewater, but not too much. They like a slightly higher elevation within the floodplain, just a bit higher than where you find marshes and mudflats. Too low and a big surge of saltwater can kill off the spruce, making what we call ghost forests.”

Coal Creek is right in the sweet spot—and still home to one of the largest intact spruce swamps on the Oregon Coast. In recent years, wetland ecologist Laura Brophy startled conservationists with estimates that Oregon has lost 95 percent of its spruce swamp habitat since the 1870s.

“Thanks to Laura, we have a much better idea of what these coastal landscapes looked like at a time when salmon were still truly abundant,” Curtis said. “Her work has helped make Sitka swamps one of the top conservation priorities on the Oregon Coast. It’s bringing the restoration community together.”

Coal Creek is one example. In 2009, the North Coast Land Conservancy acquired 75 acres here: a purchase made specifically to steward old-growth tideland spruce. Protecting existing spruce swamps is a particularly popular topic among salmon conservationists, Curtis notes—given emerging research on the importance of estuaries and tidelands for rearing juvenile salmon.

“Spruce swamps often border larger streams, which make them important refuges for juveniles all year long,” Curtis says. “In the winter, fish are looking for calmer waters away from raging streams where they can eat and rest. In the summer, the dense vegetation in these swamps mean they stay dark and cool—and that can mean life or death for fish, given our increasingly hot summers.”

“The dense vegetation in these swamps mean they stay dark and cool—and that can mean life or death for fish, given our increasingly hot summers.”

WSC Oregon North Coast Manager Cyndi Curtis

Curtis hopes that this momentum within the restoration community is just the beginning of a larger conversation with local landowners and other stakeholders. Like mangroves, the benefits of tidal spruce swamps go well beyond wild fish, she says. They’re also huge carbon sinks that, if established with rising sea levels in mind, could enhance climate and flood resiliency for coastal communities, as well as cleaner air and water.

This long-term vision is why Wild Salmon Center and coastal partners are now working with Brophy to identify places where the conditions might be right to establish future Sitka spruce swamps.

“Sitka spruce swamp can be a little picky,” Curtis says. “They need tidal influence, but like being at a higher elevation. They can tolerate a little saltwater, but too much and the spruce trees will die. With Laura, we’re now working to develop maps that can help us find locations that could be ideal for spruce swamp restoration.“

“We’re now working to develop maps that can help us find locations that could be ideal for spruce swamp restoration.”

WSC Oregon North Coast Manager Cyndi Curtis

To build these maps, WSC and our partners are using elevation mapping, historic vegetation mapping, salinity data and climate change models. Curtis says the next step is to share this data-rich picture with interested landowners and other local stakeholders: places where, together, we might nurture the Sitka spruce swamps of the future.

“The hope is that we can start this restoration work now, so that in 30 or 40 years, when sea levels are higher, we can still have these habitats that provide so many benefits for people and fish,” Curtis says.

Not least among these benefits, Curtis notes, is togetherness. Can conservationists and scientists, farmers and private landowners unite to bring back Oregon’s Sitka spruce swamps? If yes, that bodes well not just for salmon, but for coastal communities navigating other rising tides.

“The hope is that in 30 or 40 years, when sea levels are higher, we can still have these habitats that provide so many benefits for people and fish.”

WSC Oregon North Coast Manager Cyndi Curtis