If drought and heat are becoming Oregon’s new normal, it’s in everyone’s interest to adapt our water management framework to this complex reality.

Oregon’s water is one of the state’s most precious assets, and it’s never been more stretched. Below, we spotlight some of the core structural challenges we face in adapting Oregon’s water system to a new climate reality—and how Wild Salmon Center is working to build a pipeline of smart solutions that benefit all water users, including our wild fish.

Water from Oregon’s creeks, streams, and rivers sustains towns and industries, farms and ranches, and fish and wildlife. By law, all of this water belongs to the public. But the water rights system that governs this resource was built during a time that valued water only after it was taken from a stream.

We now know more about the benefits of healthy streams and rivers, like the vital habitat they provide for salmon. In 1987, Oregon created instream water rights to help protect the flows that fish need. And since then, the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife has applied for more than a thousand of these rights on streams across the state. These “rights for the river” hold the line against new withdrawals that could otherwise draw down flows below what’s needed for healthy fish habitat. Yet because older rights get first dibs on available water, these new instream water rights—and the fish they protect—can be left high and dry during times of shortage.

As our climate changes and our rivers face greater stress, we increasingly need 21st century solutions that reflect the needs of all water users. Wild Salmon Center’s Oregon Water Initiative was launched in 2020 to help adapt this system for a changing world, and address the growing threats to Oregon’s streams and the wild fish they support.

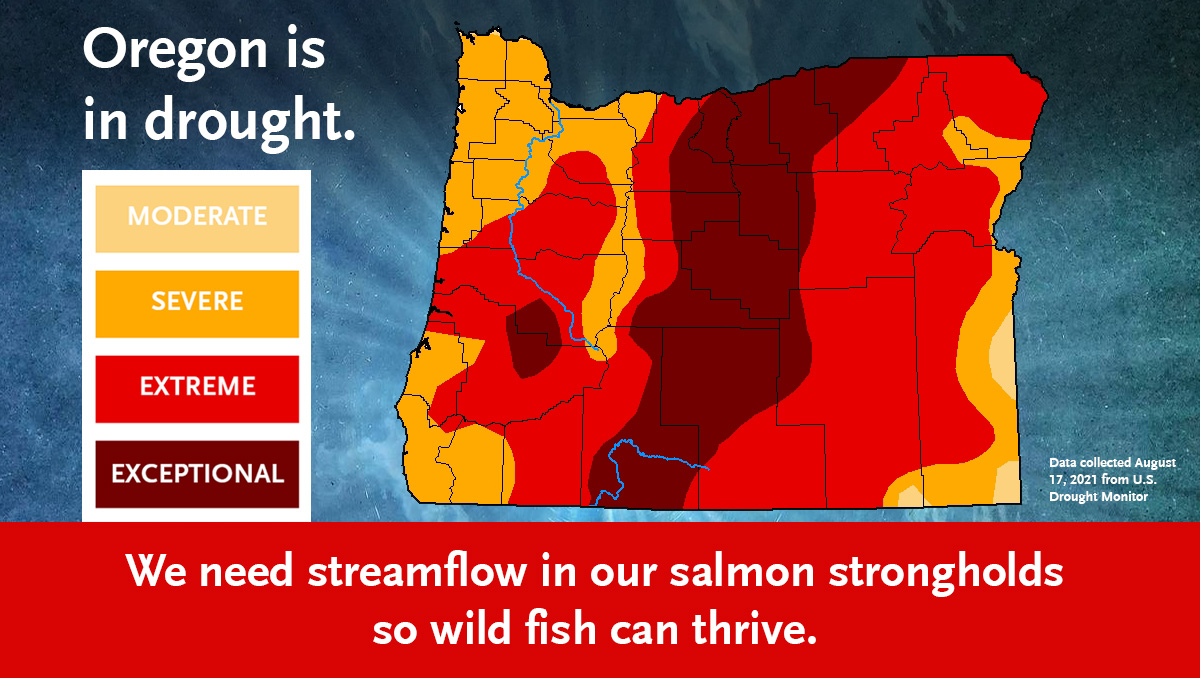

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, as of August 17, 2021, 99 percent of Oregon is in severe drought, with nearly three-quarters suffering through extreme or exceptional drought. These sweltering times are hard for everyone, from farmers and anglers to cities and industry. And for wild salmon and steelhead entering the freshwater rivers of Oregon’s seven coastal counties—all in severe drought—this summer’s low streamflows and high water temperatures bring a wide range of threats, including reduced coldwater spring inputs due to heavier groundwater pumping.

Compared to the historical record, these conditions are extraordinary. Yet there is broad scientific consensus that our region’s climate is warming and drying. If droughts like this are becoming Oregon’s new normal, it’s in everyone’s interest to adapt our water management framework to this complex reality.

Supporting research and monitoring on the streamflow needs of Oregon salmonids is a key goal of our new Oregon Water Initiative. We are working to protect and restore streamflow in the state’s stronghold rivers and help wild salmon capitalize on their built-in adaptive strategies. With better information, we can boost policies, investments, and actions that enhance wild fish resiliency.

Under Oregon law, all water belongs to the public. But of the roughly 93,000 water rights that are currently held in Oregon—rights that allow people to draw water from rivers, lakes, streams, reservoirs, and aquifers—just 15,000 require holders to monitor and report water use. And even within this smaller group, not everyone is playing by the rules. Right now, the Oregon Water Resources Department receives data from just 12,000 holders: just 13 percent of all water rights in the state.

This means that the agency that stewards Oregon’s water resources doesn’t have the data it needs to do its job effectively. WSC’s Oregon Water Initiative is advocating to boost OWRD’s data collection capacity and also expand water-use reporting requirements among rights holders. Oregon’s recently-passed budget provides some help, but more is needed, and fast.

Between climate change and population growth, it’s plain that all Oregonians need better data on how much water we use—especially in those precious places where wild salmon still thrive.

In Oregon, water rights have always operated on a “first-come, first-served” basis. This means that those with older water rights have first dibs on the water source. These senior holders can legally withdraw their full quota, even when streams and rivers are running low. In drought years, this creates obvious problems. But even in “normal” water years, this system can leave newer water rights holders—and wild fish—high and dry. This is because many of our streams are overallocated, meaning more water rights have been issued than water exists to satisfy them.

Two-thirds of Oregon’s water needs are met with surface water sources like rivers, streams, lakes, and reservoirs. But increasingly, demand exceeds available surface water, and climate change is further testing this outdated system. WSC’s Oregon Water Initiative works with legislators and water stakeholders to develop 21st century solutions that work for all of us—including Oregon’s prized wild salmon.

Hero Image