Editor’s Note: On May 8, 2023, Governor Kotek signed HB 3164 into law, following its approval in the Oregon Senate with strong bipartisan support (22-3).

For 22 years, a state program has rewarded irrigators for leasing their water rights back to streams. Will the Legislature pass HB 3164, and finally make it permanent?

In three acts, Tony Malmberg can explain why he’s a fan of a unique and imperiled program within the Oregon Water Resources Department (OWRD).

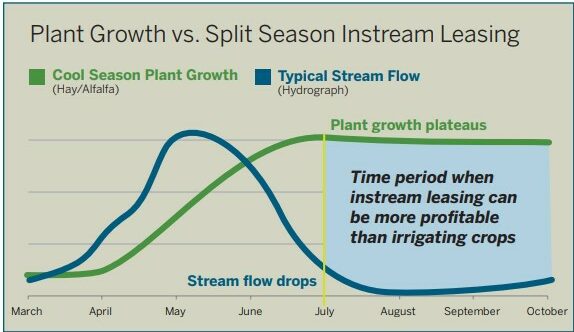

Malmberg—a beef rancher based near Union, Oregon—grows hay and other forage for his livestock. Meadow hay and alfalfa, he explains, grow best in the early summer, when weather is temperate and irrigation needs are minimal.

Act one is that first early summer cutting, when production is high, and irrigation needs are low. This part is literally the sweet spot for both Malmberg and his grass-fed livestock, benefiting from vigorous, high-sugar plants built for this season.

Then there’s mid-summer’s second cutting, when production dips, and water use goes up. The heat is full-on by the time of Malmberg’s third act, er, cutting. Now, forage crops perform abysmally even when heavily irrigated. Compared with the first cutting, Malmberg calculates that this third cutting yields just one-tenth the tonnage of forage per water inch applied.

“The hot season is when the water’s highest value is staying instream for salmon and river function.”

Tony Malmberg, author and rancher, Bunchgrass Land and Livestock

It’s a classic case of diminishing returns. And across Oregon, it’s also a tragedy for salmon and steelhead that return to streams right as agricultural producers withdraw peak water, aiming to grow one last, very thirsty crop cutting.

In 2012, Malmberg realized that rather than trying to coax cool weather plants to grow in blistering heat, it made a lot more sense to tap OWRD’s Split-Season Instream Leasing Program—a program scheduled to sunset on January 1, 2024.

This program made it possible for him to earn a reliable sum to leave his late-summer water flowing in nearby Catherine Creek, a key nursery for ESA-listed Snake River spring Chinook salmon and summer steelhead.

The same tool holds promise for salmon strongholds on the Oregon Coast, where groups involved in local restoration planning efforts are keen to find solutions that will keep streams flowing in late summer months.

“We made a shift from focusing on hay production to focusing on soil health production and grazing, improving our gross margin,” Malmberg says. “The hot season is when the water’s highest value is staying instream for salmon and river function.”

For a decade, this program was a cornerstone of Malmberg’s operations: a tool that provided revenue stability while also aligning with his values as a practitioner of nature-mimicking holistic management. (Malmberg’s an author on the topic.) But because the state’s split-season leasing program currently has a 10-year participation limit, Malmberg’s water rights became ineligible at the end of the 2021 growing season.

“Without split-season leasing last summer, the fish had less hot season water and our ranch had less income,” he says. “It doesn’t make sense to keep sunsetting this program. It doesn’t make sense for farmers, ranchers, and fish to lose out after 10 years of partnership.”

“Without split-season leasing last summer, the fish had less hot season water and our ranch had less income. It doesn’t make sense to keep sunsetting this program.”

Tony Malmberg, author and rancher, Bunchgrass Land and Livestock

Caylin Barter, Wild Salmon Center’s Oregon Water Initiative Program Director, agrees. With Oregon Water Partnership, a coalition of statewide conservation groups, Barter is working to pass HB 3164, which would remove both the program’s 10-year participation cap and the 2024 sunset. (Created as a pilot in 2001, split-season leasing has already had its sunset extended twice by the state Legislature.)

“This program has a 22-year track record as a win-win for farms and fish,” Barter says. “The bottom line is that it empowers agricultural producers to use their water rights for both growing food and restoring rivers. We need more of these tools, not less.”

Irrigator interest in this program has surged since its last reauthorization in 2013, Barter says: growing from one or two leases annually, to 10 or more during each of the last four years. Split-season leases have generated benefits for farms and fish across the state, from the Rogue to the Walla Walla and the Deschutes to the John Day. But as Malmberg notes, the eligibility limit means that irrigators who shift their operations to the split-season model take a financial hit when they cap out. Meanwhile, each looming sunset dampens interest from new potential lessors.

According to Barter, HB 3164 provides an easy and cost-free way to make the program a reliable investment of an irrigator’s time and resources.

For WSC and conservation partners like The Freshwater Trust and Trout Unlimited, it’s also just a common sense strategy for restoring depleted stream flows for fish. In Oregon, agriculture is the state’s largest water user by far, with roughly 85 percent of all water use statewide going to irrigating farms and ranches. So the sector is a natural place to seek voluntary solutions that improve the state’s water efficiency.

“This program empowers agricultural producers to use their water rights for both growing food and restoring rivers. We need more of these tools, not less.”

WSC Oregon Water Initiative Program Director Caylin Barter

“Oregon’s water future is growing more challenging with every day we fail to act,” Barter says. “Now is the time to make sure that farmers and ranchers have the tools they need to be the best possible stewards of this public resource. Because we know that everyone will lose if we keep kicking the can down the road.”

Already, she says, support for HB 3164 is broad and bipartisan, sponsored by both Representatives Mark Owens (R-Crane) and Ken Helm (D-Beaverton). Advocates for the bill include farming interests, conservation groups, cities, irrigation districts, ranchers like Malmberg, and Tribes.

Lisa Ganuelas, a member of the Board of Trustees of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, was among the supporters of HB 3164 who testified at a March 2 public hearing.

“Our efforts to re-establish fisheries in the Walla Walla, Grande Ronde, and Wallowa are critically dependent upon this important tool, which provides flows during the late summer when returning salmon need it most,” Ganuelas testified. “Without this important tool, our restoration efforts in these basins will falter.”

That broad support was echoed on the House floor later in March with a near-unanimous vote (55-2) to approve HB 3164. The bill now awaits its first hearing in the Senate Natural Resources Committee. Malmberg, for one, stands ready for an encore performance in a program that benefits both his ranch and the ecosystem that sustains it—especially the wild salmon in Catherine Creek.

“We purchased this property, in part, because the irrigation water came from one the most critical Chinook salmon streams in the Pacific Northwest,” he says. “We believe that the practices that support endangered species add diversity and complexity to the entire environment, including livestock.”

According to Malmberg, the moral of the story is that what’s good for endangered species like salmon is good for all of us, from grass to table. For him, a happily restored salmon ecosystem should be the real curtain closer. End scene.

“We believe that the practices that support endangered species add diversity and complexity to the entire environment, including livestock. ”

Tony Malmberg, author and rancher, Bunchgrass Land and Livestock

Hero Image

Hero Image (Home Page Section)