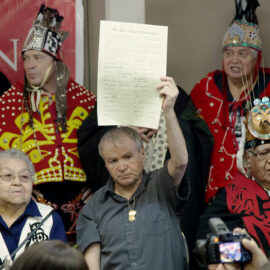

A coalition declares Lelu Island and Flora Bank permanently protected.

An unprecedented coalition of First Nations leaders, local residents and federal and provincial politicians in northern British Columbia declared in late January that Lelu Island and Flora Bank at the mouth of the Skeena River are permanently protected from industrial development. The area is critical habitat for wild salmon but is under pressure from a $12 billion gas export terminal being pushed by Malaysia’s state owned oil and gas conglomerate, Petronas.

Salmon supporters can now sign on to the Lelu Island Declaration.

The declaration was the culmination of a two-day Salmon Nation Summit in the lower Skeena River port of Prince Rupert, BC, where more than 300 hereditary and elected First Nations leaders, scientists, politicians, commercial and sport fishermen, and other northern residents came together to speak out in defense of wild salmon. Wild Salmon Center joined the gathering with SkeenaWild and Friends of Wild Salmon – two of the local conservation groups that helped organize the summit.

Signatories to the declaration included hereditary leaders from the Nine Allied Tribes of the Lax Kw’alaams First Nation, some of whom have claimed traditional title to Lelu Island. The document was also signed by hereditary leaders of the Gitxsan, Wet’suwet’en, Lake Babine, and Haisla First Nations. Grand Chief Stewart Phillip of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs also signed the declaration.

The Petronas project was also emphatically rejected by the region’s member of parliament, Nathan Cullen, and the three regional members of British Columbia’s legislative assembly.

“This project isn’t going to happen. This project can’t happen,” Cullen said.

The signing presents a major obstacle to Petronas, and it deals a huge blow to the BC provincial government’s stated aim to get major LNG plants under construction before next year’s provincial election.

“The Lelu Declaration sends a powerful message to (BC) Premier Clark and Prime Minister Trudeau,” said Hereditary Chief Yahaan of the Gitwilgyoots Tribe of the Lax Kw’alaams, who has filed for traditional title to Lelu Island. “The support to stop this LNG project is overwhelming. Nations are united from the headwaters of the Skeena River to the ocean. Together, we will fight this to the end.”

The declaration states: “The undersigned First Nation leaders and citizens of the Nine Allied Tribes of Lax Kw’alaams hereby declare that Lelu Island, and Flora and Agnew Banks, are hereby protected for all time, as a refuge for wild salmon and marine resources, and are to be held in trust for all future generations.”

A recent study conducted by lower Skeena tribes and Simon Fraser University has shown that Flora Bank is the linchpin for the entire Skeena salmon system. At least 40 populations of juveniles born throughout river system use the eelgrass beds on the bank for at least a few weeks during their transition to salt water. The Skeena hosts strong runs of five species of Pacific salmon and steelhead.

The latest plans from Petronas local affiliate, PacificNorthwest LNG, have the developers building a Golden Gate Bridge-sized causeway over the bank to service 350 tankers a year at a new deepwater port. Industry funded studies have shown little risk to salmon. Government regulators rejected that notion three times before finally agreeing with gas interests’ studies and allowing the project to proceed to a full review this spring.

BC Premier Christy Clark, major proponent of gas development, quickly lashed out at supporters of the Lelu Island Declaration, labeling them “forces of no.”

“The Premier is right about one thing, and only one thing – we are a force, a growing force, and we are a force to be reckoned with,” said Des Nobels, long-time North Coast fisherman, co-chair of the historic Salmon Nation Summit, and an elected municipal leader with the Skeena-Queen Charlotte Regional District. “If she thinks she can just come up here and destroy critical salmon habitat, to threaten the very basis of an economy that has shaped our culture and sustained our families for untold generations, well, of course we say ‘no’ to that.”

The combined commercial, recreational and subsistence fisheries economy in the Skeena is valued at $110 million a year.

Hero Image