This summer, drought and heat are again challenging Pacific Northwest salmon rivers. But 150 years of poor decision-making are what’s brought salmon runs to the brink—and there’s plenty we can still do to reverse those harms.

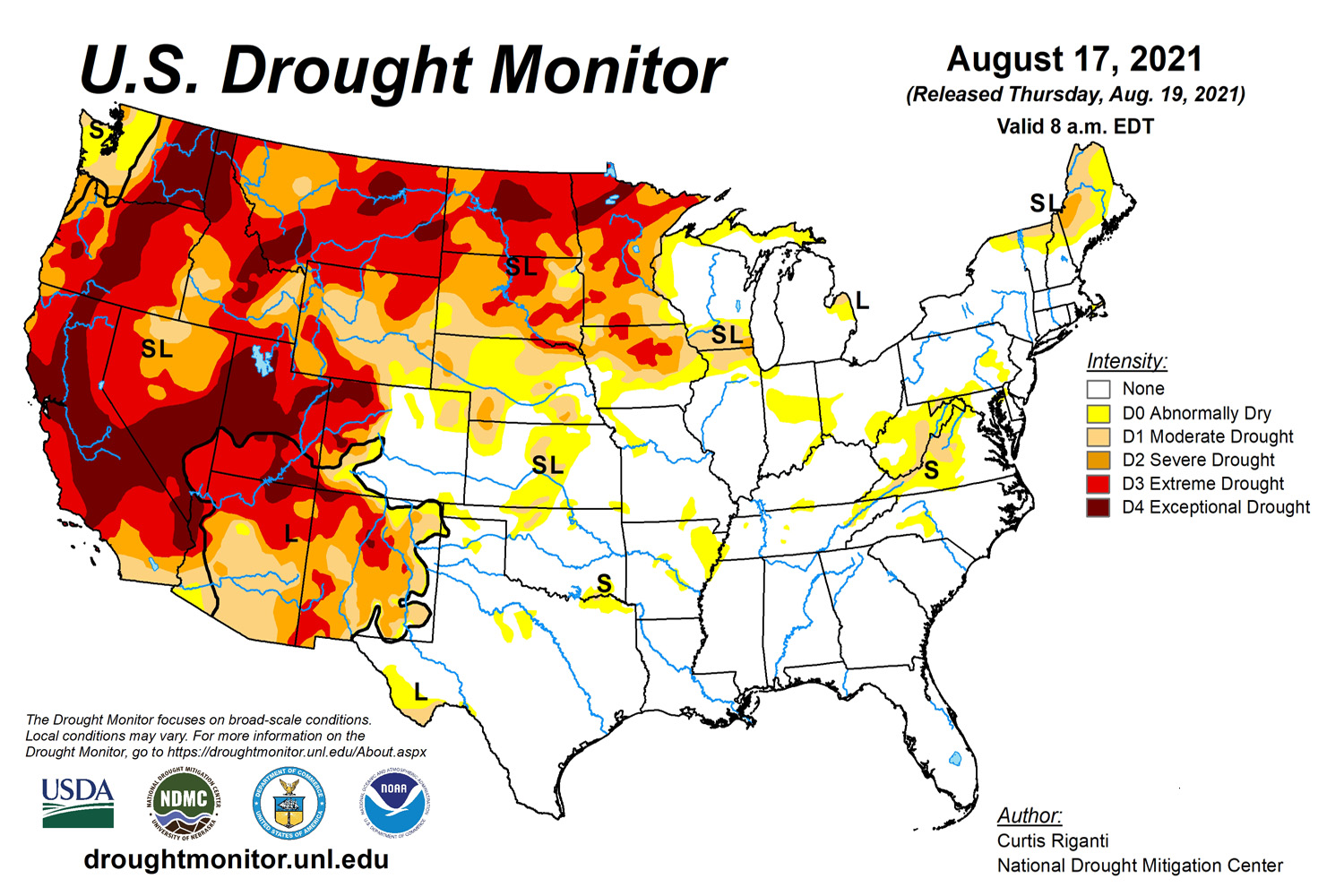

Summer 2021 continues to be another tough one for wild salmon across the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia. Struggling, heat-stressed runs in the Columbia and Sacramento river systems are making national news, with climate change-induced drought and heat waves called out as the main culprit.

It’s true that cyclical drought, combined with the onset of a drier, warmer climate regime in the Northwest, are stretching salmon rivers to the breaking point. We may also still be seeing the effects of “The Blob”—a slab of warm ocean water that frequented Northwest waters and the Gulf of Alaska between 2014 and 2019, altering ocean food webs including salmon forage.

But we need a reality check. One hundred and fifty years of poor human decisions are what has brought salmon runs to the brink of collapse. And if we want to help salmon adapt to a changing climate, we must reverse those decisions quickly. Given the space to adapt, wild salmon can survive and even thrive in the face of change. As a species, they’ve proven remarkably resilient over the last 18 million years.

Given the space to adapt, wild salmon can survive and even thrive in the face of change. As a species, they’ve proven remarkably resilient over the last 18 million years.

Earlier this year, Wild Salmon Center released “Ready for Change,” a framework to drive priorities and actions for resource managers and others who want to help salmon adapt to climate change. This approach requires resilience-building on two fronts: 1) restoring and protecting watersheds in a way that makes them less sensitive to climate impacts like heat waves and drought; and 2) protecting and expanding wild salmon’s natural adaptability and built-in survival mechanisms—mechanisms, like the ability to find and hold in cold water, that are driven by their genetic diversity.

By reversing harm to watersheds and restoring healthy natural functions like cold water flows, stream shading, and connectivity to wetlands and estuaries, we give salmon populations the space they need to adapt to changing conditions.

And by restoring salmon genetic diversity, along with a diversity of life histories—wild salmon’s varied ocean life cycles, run timings, and other adaptations—we help wild salmon leverage their full suite of survival strategies, honed through millions of years of evolution.

If this summer’s climate events lay bare the challenges for salmon survival, they also expose our slowness to take the concrete actions that we know will improve salmon adaptation. For years, we’ve known exactly what the Northwest’s wild salmon need to survive and adapt. And yet, we’re still not doing this work on a scale or pace that matches our rapidly changing climate. We must accelerate the restoration of rivers and wild salmon diversity. And we must act now.

EIGHT THINGS WE CAN DO RIGHT NOW

By refocusing salmon habitat and fish management on the things most important for wild salmon resilience, we can make meaningful difference for this keystone species in the face of climate change. Among the many local and regional actions we can take, here are eight high-leverage decisions that will make an outsized impact for wild salmon right now.

1. Remove the Lower Snake River dams.

Restoring the lower Snake River replaces 140 miles of lethally hot reservoirs with free-flowing cold water habitat. This action also fully opens 30,000 stream miles of upriver habitat to diverse populations of Chinook and steelhead.

2. Improve Oregon’s streamside logging protections.

Salmon start and end their lives in small forest streams. Oregon continues to have the weakest streamside logging rules on the West Coast. Right now, timber and conservation groups are at the table negotiating new rules right now for 11 million acres of private land—which represents a crucial potential turning point for wild salmon.

3. Enhance streamflow protections in key Oregon river systems and approve 59 new instream water rights.

All summer long, Oregon’s oversubscribed water system fails salmon. In some watersheds, there are more rights to water than water in streams, leaving both fish and newer water users high and dry. Meanwhile, Oregon has yet to invest the resources to form the state’s water resources “strategy” into an actionable plan that prioritizes restoring cold flows and groundwater in the highest impact areas for salmon. We can start by winning approval for 59 new instream water right applications for southern Oregon salmon rivers like the Rogue.

4. Accelerate the removal of Washington culverts.

Washington has thousands of barriers blocking hundreds of miles of high value, cold-water habitat on the Olympic Peninsula. Right now, WSC and partners are developing 50 shovel-ready top-priority projects that would open more than 100 stream miles on the Washington Coast—projects that could be accelerated with new funding under the federal infrastructure bill.

5. List spring Chinook under the Endangered Species Act in Oregon, and California.

Springers have thrived for hundreds of thousands of years by climbing high up into watersheds before low, hot summer flows. But for the past 150 years, they’ve been increasingly blocked by dams and hurt by management actions across their range. Federal agencies should follow the lead of California Fish and Game, which recently protected spring Chinook in the Klamath and Trinity river systems.

6. Manage wild steelhead for resilience in Oregon and Washington.

A more conservative salmonid management approach—one that allows small wild steelhead runs room to recover as we gather data—is needed in Oregon’s South Coast Multi-Species Plan. And on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, we must do a better job of managing fishing pressure on wild populations to give fish the chance to rebuild and adapt to changing conditions.

7. Implement more selective fishing techniques.

The wave of the future in commercial salmon harvest is the use of old fishing techniques that protect a diversity of runs and wild salmon’s natural ability to adapt. We must learn from successful revitalization of traditional selective fishing practices, including the Columbia River’s fish trap, Lummi Island reef netting, and Harrison River beach seining. Each of these models hold promise for live capture of salmon close to their home rivers in a way that allows vulnerable populations to escape commercial harvest.

8. Permanently Protect Bristol Bay.

In our new climate reality, climate resilient strongholds have become even more important. Bristol Bay’s diverse wild sockeye populations—which approached near-record runs this year overall—give us more evidence of the ability of salmon to adapt to current conditions and even thrive. That’s why it’s more important than ever that we protect this place from the threat of Pebble Mine.

Hero Image