Our first Polsky Science Fellow is building a groundbreaking genetics map for Pacific Chinook and steelhead.

Dr. Tasha Thompson has been a mountaineering guide and a wildland firefighter. She’s traveled throughout southeast Asia, owned motorcycles and mountain bikes, and conducted research on subjects ranging from HIV to walruses.

But in 2015, while doing a lab rotation as a doctoral candidate in UC-Davis’s genetics and genomics program, Dr. Thompson found her true passion: salmon.

“They’re amazing,” says Dr. Thompson. “To witness how evolution has shaped this species—and continues to do so—is just endlessly fascinating.”

She’s not your average salmon-fascinated bystander. With her spouse Dr. Mike Miller, also a geneticist, Dr. Thompson is now a leading scholar in salmon conservation science. And she definitely takes her work home with her; in 2020, as Oregon’s Archie Creek Fire approached her family’s home on the North Umpqua River, a collection of newly-acquired salmon fin clip samples was among the precious few things she grabbed in the last-minute evacuation.

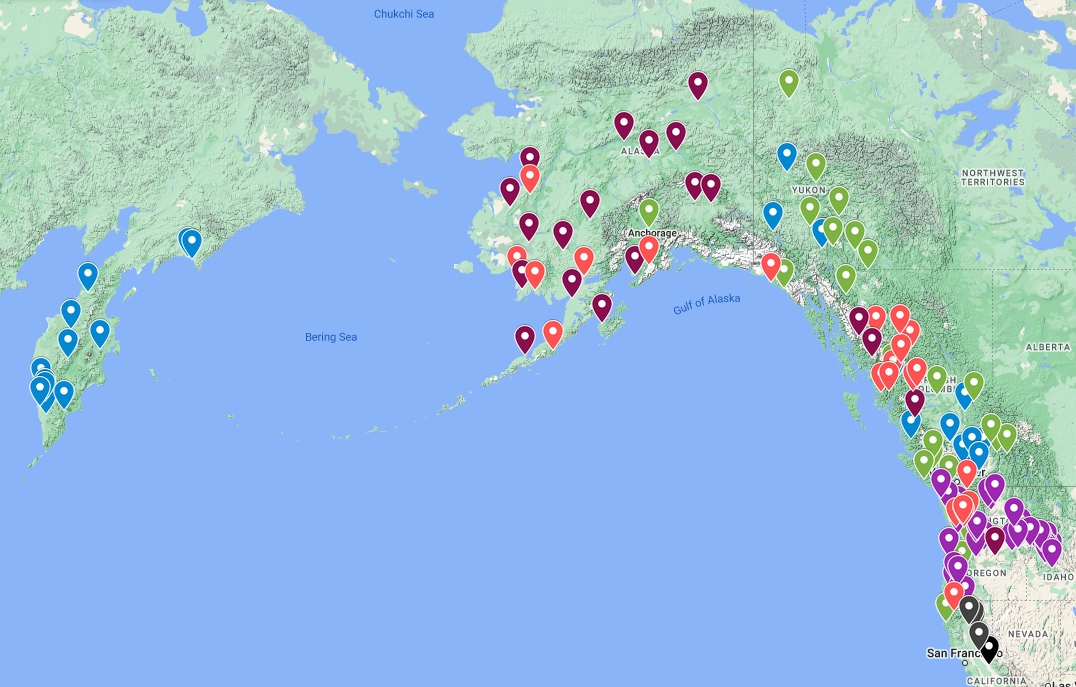

Now, as Wild Salmon Center’s first Polsky Science Fellow, Dr. Thompson is working to literally crack the code that first fascinated her. For the next two years, she’s dedicating her time to a project of unprecedented scope: creating a range-wide whole-genome database for both Chinook salmon and steelhead.

“Our database will essentially serve as an atlas for genetic diversity,” she says. “Our goal is to provide a brand new tool for researchers—one that they can use to better understand how any discoveries made in one river might play out across the rest of the species’ range.”

According to WSC Science Director Dr. Matt Sloat, this foundational data could enable an entirely new generation of salmon conservation science.

“Dr. Thompson’s research was advancing the world of salmon conservation genetics even before she joined our team,” Dr. Sloat says. “But the work she’s doing now as a Polsky Fellow has truly international implications. It could help unlock rafts of promising new conservation strategies across the North Pacific.”

“The work that Dr. Thompson is doing has truly international implications. It could help unlock rafts of promising new conservation strategies across the North Pacific.”

WSC Science Director Dr. Matt Sloat

Dr. Thompson was part of the team that in 2017 discovered the specific gene within Chinook salmon responsible for fall and spring run timing. Then, in 2018, Dr. Thompson led a groundbreaking research project which found that one key gene factored into the fast decline of spring Chinook in Oregon’s Upper Rogue River—a system where fall Chinook populations are now crowding out other genotypes.

Together, these discoveries have upended schools of thought about how to best protect spring-run salmon populations.

“We now know that if we lose the gene for spring Chinook in a river, we can’t expect that run to ever recover on its own, no matter how much we might improve water conditions or restore habitat,” Dr. Thompson says.

Thanks to her Polsky Fellowship, Dr. Thompson is now building on this earlier genetics work to launch her dream project: a comprehensive genetic map of wild Chinook across the North Pacific Rim to western Kamchatka.

Thanks to her Polsky Fellowship, Dr. Thompson is now launching her dream project: a comprehensive genetic map of wild Chinook across the North Pacific Rim to western Kamchatka.

“I’ve been thinking about a Chinook genomic map for about five years, and talking with Matt about it from the beginning,” Dr. Thompson says. “The data will help us develop tools to pinpoint exactly where juveniles from different runs are rearing, accurately survey and monitor life history diversity, and develop smarter climate models, among other innovations.”

Chinook salmon, she says, may just be the start point for this ambitious, first-of-its-kind project. With the DNA sequencing now complete for the species, Dr. Thompson and our science team are pivoting to analysis—while also launching a new whole-genome mapping project for steelhead, a species with even greater run timing diversity than Chinook.

In the next year, she says, the WSC Science Team aims to publish its initial Chinook findings and make this data publicly available to all researchers.

“Our goal is to open up this resource for everyone,” Dr. Thompson says. “There are so many discoveries ahead of us. For example, we’re just starting to understand how finely-tuned these genetic mechanisms are, dictating the difference not only between spring and fall Chinook, but also between earlier or later-returning fish in the same spring run.”

“There are potentially endless conservation projects that this data could enable,” she adds.

In the quest to better understand and protect wild salmon, we’re honored to call Dr. Thompson a colleague. We’re excited to see where this fascinating genetic journey leads next.

“Our goal is to open up this resource for everyone. There are potentially endless conservation projects that this data could enable.”

WSC Polsky Science Fellow Dr. Tasha Thompson

Hero Image