In a Coos River tributary, we’re restoring safe passage for salmon. And they’re showing up.

Tioga Falls, on Oregon’s Central Coast, has long been a chokepoint for migrating wild fish.

Above the falls stretch fourteen miles of exceptional wild fish habitat along Tioga Creek, a remote tributary of the Coos River. But climbing this cascade has always been tricky for salmon and steelhead. And that was before commercial timber came to this watershed, altering so much of the salmon-rich basin that the Miluk people (today part of the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians, the Coquille Indian Tribe, and the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians) still call home.

What came next reads like a cautionary tale for habitat restoration managers today.

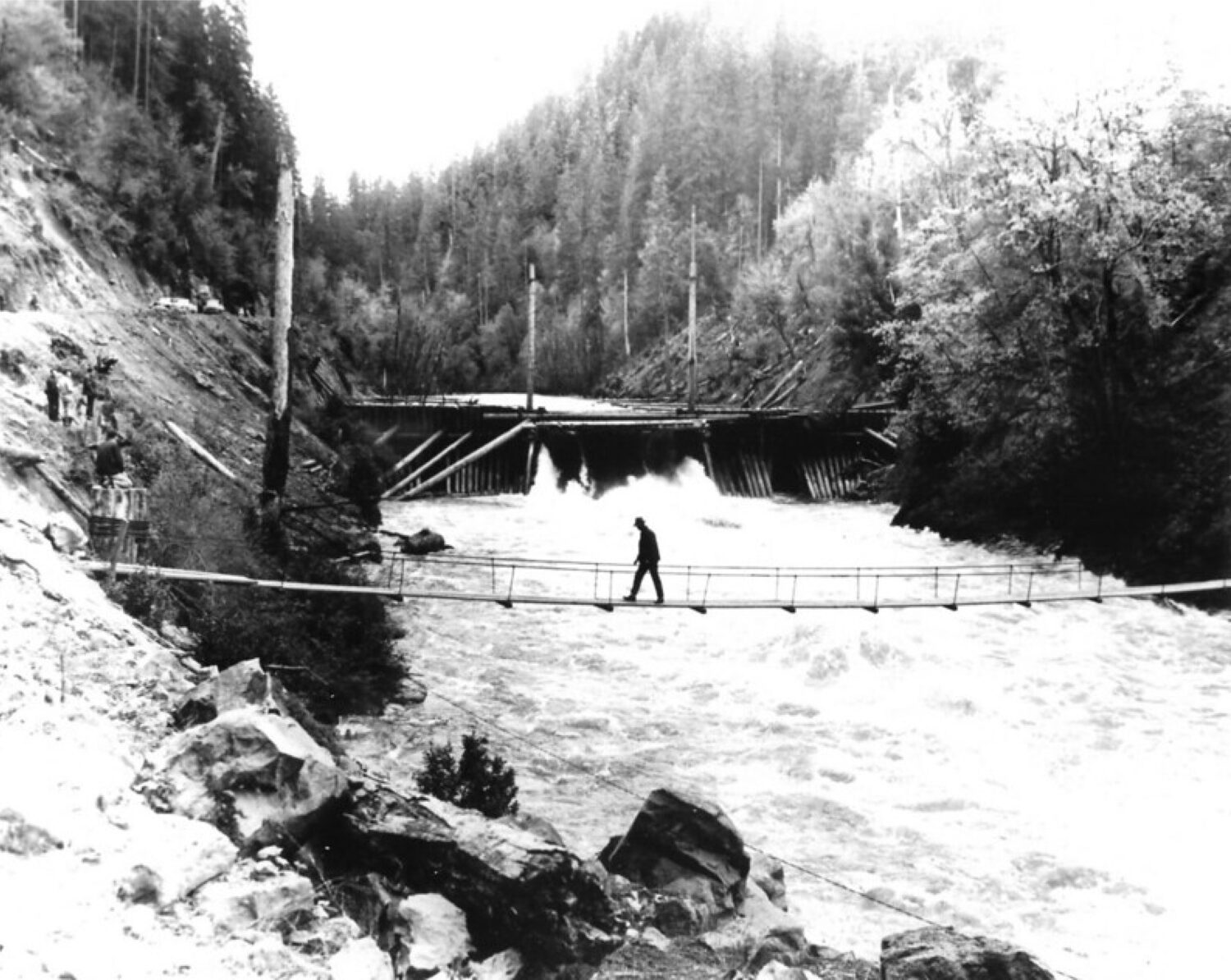

In the first half of the 20th century, loggers hauled massive trees down into Tioga Creek, staging them for mass transport behind what was Oregon’s largest splash dam, located just downstream. Over time, these powerful moving logjams scoured the bedrock above and below the falls, washing away sediment and deepening this natural fish barrier. These activities transformed what was already a difficult jump into a nearly impassable 10-foot wall.

The splash dam came down in 1957. In the decades since, state agencies and conservation interests have tried, and largely failed, to restore fish passage at Tioga Falls.

In the 1960s, the Oregon Fish Commission (later the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife) made its first attempt at cutting a rock ladder up the sheet of bedrock; it didn’t work. A little more than a decade later, the agency dug down further, scooping out several large, hollow concrete steps. But this well-intentioned fish ladder instead became a seasonal barrier itself, clogging with debris and often impeding adult fish passage. Sometimes, the ladder would even leave fish stranded completely.

“The ladder has demanded frequent maintenance from ODFW, which isn’t really feasible given the creek’s remoteness,” says Wild Salmon Center Habitat Restoration Engineer Michelle Cramer. “We knew we could build a more natural and self-sustaining fishway for Tioga Creek.”

In the decades since, state agencies and conservation interests have tried, and largely failed, to restore fish passage at Tioga Falls.

Learning from these past failed approaches, Wild Salmon Center and a team of partners came up with a new fish passage plan—and this time, it’s working. In 2022, WSC won grant funding from NOAA Fisheries to build a nature-mimicking path up through Tioga Falls. Our design team—which also included ODFW, the Oregon Department of Forestry, the Bureau of Land Management, and the Coos Watershed Association—created a carefully engineered plan for a set of self-cleaning chutes and pools adjacent to ODFW’s fish ladder. It’s a design inspired by a similar, and successful, recent restoration project at Stulls Falls on the nearby West Fork Millicoma River.

This past summer, the Coos Watershed Association got to work as the project lead, cutting three channels and a series of notches into the bedrock. According to CWA Restoration Project Manager Allison Tarbox, crews utilized everything from heavy duty saws and jack hammers to small rock hammers to chip away at the slab, creating graduated lifts, small resting pools, and carefully extended natural potholes.

Learning from these past failed approaches, Wild Salmon Center and a team of partners came up with a new fish passage plan—and this time, it’s working.

“Tioga Creek is one of the highest producing wild fish streams in the Coos Basin, and the falls represent the last obstruction for its migratory fish in the mainstem,” Tarbox says. “So we were all extremely motivated to help get this problem fixed.”

Work on the channels wrapped up in late summer, and crews installed time-lapse cameras to take photos every 15 minutes. Then, the team waited for autumn rains to arrive—flows that draw both ESA-listed Oregon Coast coho and fall Chinook salmon to the base of the falls. Flows that, this time, would hopefully entice them to try out the new way up.

In mid-November, Tarbox got the call: coho had been sighted above the falls. These agile climbers had found the new channels and made the leap. Tarbox rushed out to the project site, and counted at least 20 coho with her own eyes.

“So yes, we’re passing fish, which is hugely satisfying to see,” Tarbox said. “But while we’re on the right track, we also know our work here isn’t done yet.”

She points to the fall Chinook who have also been spotted below the falls: fish that don’t—yet—seem to be finding the right flows for a successful climb. Her team is closely monitoring both successful and failed fish attempts, looking for ways that crews can improve the new fishway when low flows return next summer.

In mid-November, Tarbox got the call: coho had been sighted above the falls.

According to Cramer, those summer 2024 enhancements will happen alongside work to revitalize upstream habitat complexity in Tioga Creek. That includes installing large wood structures to help correct another misguided human intervention following the splash dam. In a practice called “stream cleaning,” trees and other “debris” were aggressively cleared from Tioga Creek—a practice that some thought would help fish, but in fact degraded their spawning and rearing habitat, while further altering the creek’s natural hydraulics.

“We definitely want to see more coho and Chinook up above the falls,” Cramer says. “This is upstream habitat that we know fish used before all the splash dams, log drives, and stream cleaning.”

For ESA-listed Oregon Coast coho in particular, access to this kind of intact, high-quality habitat has never been more critical, as we work to help the species recover. That’s true here in the Coos Basin, and up and down the Oregon Coast.

On Tioga Creek, at least, the path is now clear for one rocky restoration story to come full circle.

For coho, access to intact, high-quality habitat has never been more critical. That’s true here in the Coos Basin, and up and down the Oregon Coast.

Hero Image

Hero Image (Home Page Section)