The mystery of the Hoh River Spring Chinook

With our partners, we’re tracking fish deep into the Olympic Peninsula. This work could make a big difference for Hoh Tribal fishers.

Like a crooked elbow, a long sandbar stretches across the mouth of the Hoh River on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, a thin buffer from the Pacific Ocean. Just inside the bar, calm, brackish water offers refuge for salmon.

Spring Chinook in particular, love this big, emerald blue pool just yards from the sea. Many linger here in summer and early fall: a reason why it’s long been an important fishing area for members of the Hoh Tribe.

And yet, in both 2020 and 2022, the Hoh Tribe largely closed its spring Chinook fishery, concerned by forecasts predicting poor returns of salmon to this 56-mile system. The Tribe’s closures aimed to help the run rebound. And in 2024, Tribal experts noted that escapement numbers—adult fish that pass upriver before harvest begins—were the highest since 2002.

Photo Credit: Luke Kelly, Trout Unlimited

The Tribe has long focused on making sure escapement goals are met upriver. But what of the large numbers of spring Chinook pooling in the estuary?

“Even in years when we expected low numbers of Chinook and the fishery was closed, we still observed many Chinook hanging out in the lower river,” says James Losee, Wild Salmon Center’s Senior Wild Fish Manager for Washington State. “It didn’t always make sense with what we were seeing upriver.”

“Even in years when we expected low numbers of Chinook, we still observed many hanging out in the lower river. It didn’t always make sense.”

Wild Salmon Center Washington Senior Wild Fish Manager James Losee

For Tribal fishery managers and research partners like Losee, that potential disconnect raised a question: what if these fish in the estuary aren’t actually Hoh River salmon?

“Salmon migrating along ocean coastlines have been known to take breaks on their way home,” Losee says. “They’re called “dip-ins.”

With its cold, glacial waters, Losee says, the Hoh estuary would be a fantastic place to slow down for a bit on the long journey back to other home rivers.

“If these fish lingering in the estuary are tourists, just stopping by to visit, the next thing we’d want to know is if they’re from large healthy populations,” Losee says. “If that’s the case, that might reopen some fishing options for Tribal fishers while we work to figure out what’s really going on with the Hoh’s native wild fish.”

To solve these interlocking mysteries, the Hoh Tribe invited Wild Salmon Center and other partners to join forces to genetically identify these fish and acoustically track them, potentially across oceans.

“Our first duty is to protect the fish in our home rivers,” says Bernard Afterbuffalo, a Hoh Tribal member and the Tribe’s Natural Resources Technician. “But fishing is also our way of life. That’s why we’re very interested to see what we can learn from our fish tracking project.”

“Fishing is our way of life. That’s why we’re very interested to see what we can learn from our fish tracking project.”

Hoh Tribe Natural Resources Technician Bernard Afterbuffalo

The project began in earnest in spring and summer 2025, as Losee and Tribal fishery staff spent days in the Hoh River estuary simulating the traditional Tribal fishery to catch adult spring Chinook.

Moving quickly between live wells of river water, the team safely sedated each fish and performed a three-minute surgery to attach what Losee calls a “backpack”—an acoustically-tagged saddle to broadcast the fish’s location. Then, the team carefully released each fish back into the water.

The team also spent time bushwhacking throughout the watershed. Near the edges of the Hoh mainstem and several tributaries, they installed more than a dozen telemetry devices—each resembling a two-liter bottle of soda pop—to listen for fish with acoustic tags and report back.

Now, the tracking project enters data collection. For the next two years, the Hoh’s listening devices will record any passing spring Chinook wearing a backpack (along with additional fish species tagged from this and other projects).

Combined with genetic analysis, this information can help solve the mystery of whether any of the estuary springers are native to the Hoh.

To track the movements of the rest—potential dip-ins from other rivers—the team is tapping into a growing network of similar telemetry devices up and down the Pacific Coast.

Photo Credit: Wild Salmon Center

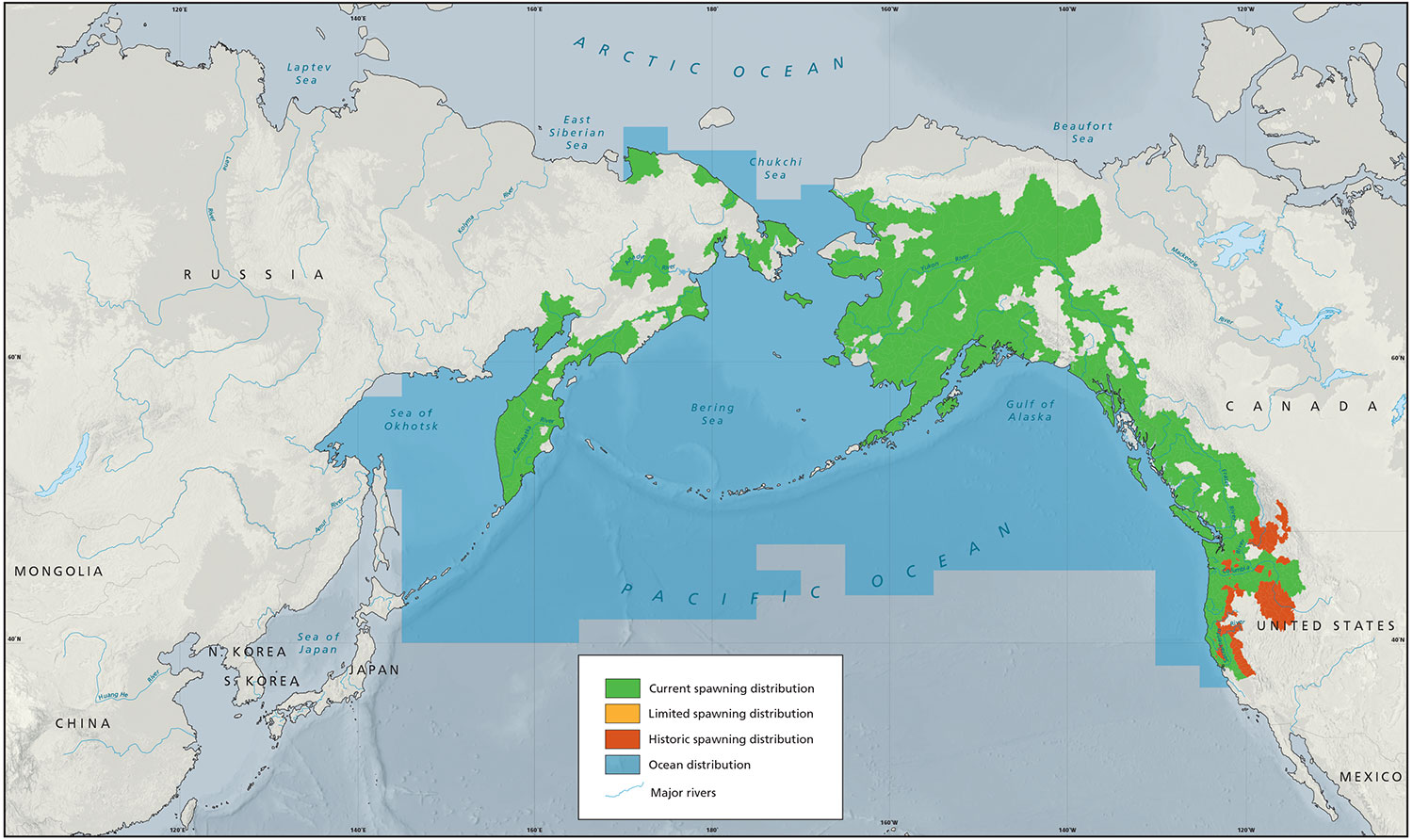

“This is an exciting time to be a salmon tracker,” Losee says. “Pretty much anywhere from Alaska to California, we can see almost in real-time where these salmon go. We can basically follow them to their home rivers.”

“This is an exciting time to be a salmon tracker. Anywhere from Alaska to California, we can see almost in real-time where these salmon go.”

Wild Salmon Center Washington Senior Wild Fish Manager James Losee

Photo Credit: © Atlas of Pacific Salmon (X. Augerot) 2005

If Chinook salmon caught in the Hoh ultimately travel on to other home rivers, it could mean that some could be harvested without impacting Hoh spring Chinook. This ambitious project could also shed light on questions that go well beyond the Hoh—such as how best to balance fishing and conservation efforts up and down the West Coast.

“When we decide whether to fish or not, these are decisions we can make here as a Tribe, within our community,” Afterbuffalo says. “But if we do our part in the Hoh to recover salmon and yet fish keep suffering, then the solutions need to be bigger as well.”

Data collection like this is a big step in the right direction, Losee says. The more we know about how Hoh salmon move in ocean and freshwater, the more options the Hoh Tribe has to steward its fishery and advance international salmon science.

Across the Pacific, fish tracking projects like this are on the rise—starting with work by Wild Salmon Center and our partners to bring this novel science to other river systems across the Pacific Rim.

Photo Credit: Wild Salmon Center

“What we learn in the Hoh could support Tribal fishers to get back on the water sooner,” Losee says. “But this project is also a perfect example of the nexus between salmon science, fish management, and treaty rights. Big picture science like this really does show what could be possible in other salmon rivers.”

“Big picture science like this really does show what could be possible in other salmon rivers.”

Wild Salmon Center Washington Senior Wild Fish Manager James Losee

Photo Credit: Wild Salmon Center

Hero Image (Home Page Section)

Related News

For the Makah, WWII is still a problem for salmon streamsJune 18, 2025 Salmon Need Cold Water. We’re Tracking It Across Continents.September 19, 2023 Hot or Not? On the Quillayute River, Tribal Scientists Test the WaterNovember 17, 2021Join the Movement

Stay up-to-date on what we’re doing for wild salmon and how you can help.

SUBSCRIBE