On British Columbia’s Central Coast, a failing chum fishery left a wide wake of unintended impacts. Now there’s hope that a years-long commercial fishing pause can help rebuild the region’s wild fish runs.

For years, First Nations and conservation groups in British Columbia warned federal fisheries managers that Central Coast chum salmon were in trouble.

“Knowledge holders had been saying, ‘hey, there are no chum,’ yet the commercial fishery in the region remained open,” says Wild Salmon Center Salmon Watershed Scientist Dr. Will Atlas. “We wanted to put a number on the population declines that we’d been hearing about.”

Knowledge holders had been saying, ‘hey, there are no chum,’ yet the commercial fishery in the region remained open. We wanted to put a number on the population declines that we’d been hearing about.

Dr. Will Atlas, Wild Salmon Center Salmon Watershed Scientist

With a team of First Nations partners and fellow scientists, Dr. Atlas combed through 60 years of raw data from Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). The team’s findings—peer-reviewed and published in the Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences—show that between 1960 and 2020, wild chum salmon populations declined 90 percent within Central Coast fisheries management areas 6-9, from the Douglas Channel south to Rivers Inlet.

Following the last two years’ wild chum returns—the worst in the region’s history—this historical perspective showed a fishery clearly teetering on the brink.

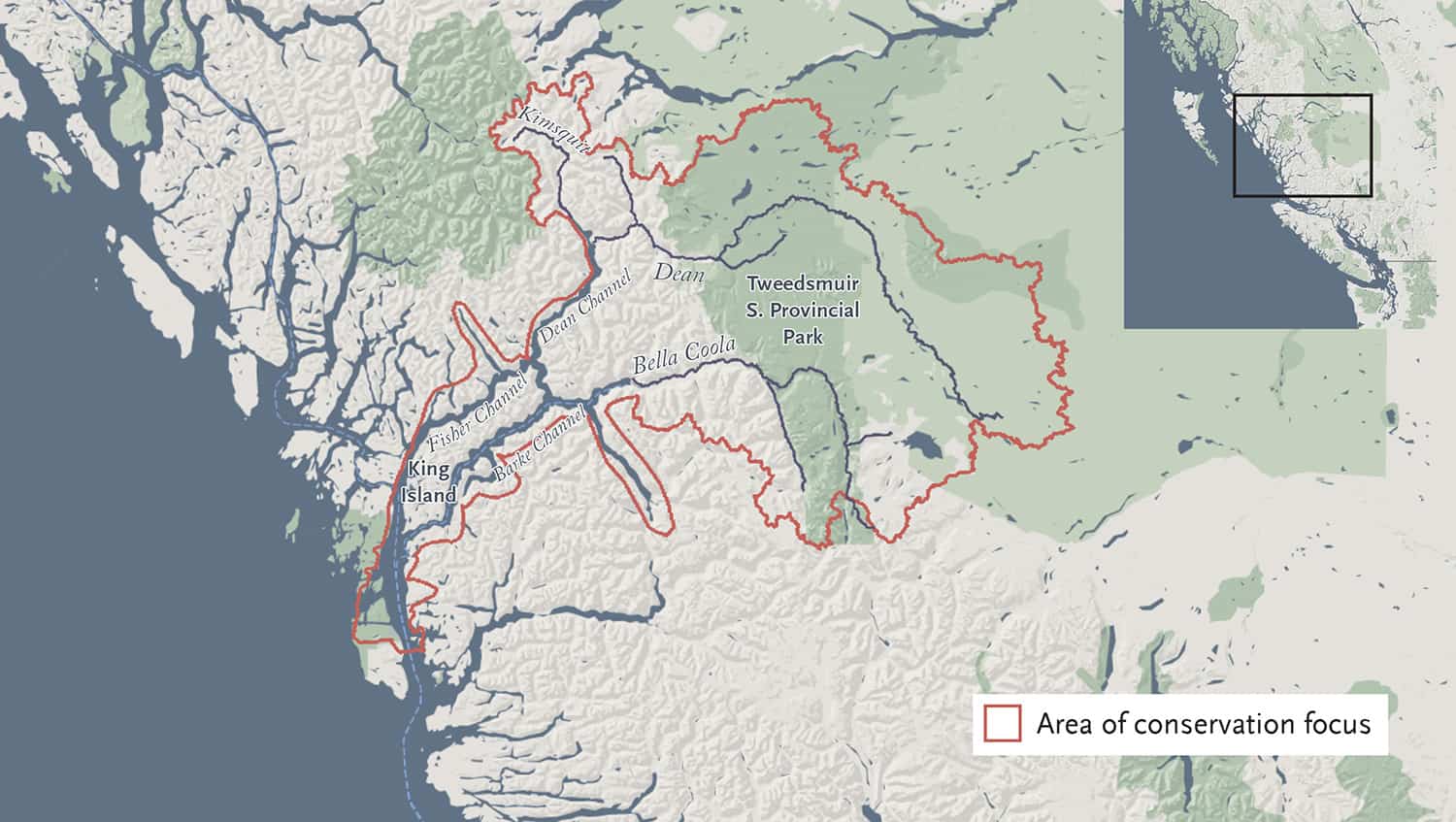

On the heels of the study’s July 12 publication, DFO moved to extend a 2021 closure of Area 8—the region’s last open chum salmon fishery. That closure, which applies to the Fisher, Dean and Burke Channels, North and South Bentinct Arms, and Fitz Hugh Sound, will last for at least a full generation of chum, likely four years at minimum.

For Scott Carlson, the Executive Director of the Coastal Rivers Conservancy, a nonprofit that Wild Salmon Center helped to launch, the move shows serious commitment at the Federal ministerial level towards rebuilding the region’s wild salmon and steelhead runs.

“This closure will help take pressure off chum, as well as many other species that have been caught as bycatch for the last 40 years, including sockeye, Chinook, and steelhead,” Carlson says. “It also gives us a real opportunity to start reforming this fishery.”

This closure will help take pressure off chum, as well as many other species that have been caught as bycatch for the last 40 years, including sockeye, Chinook, and steelhead. It also gives us a real opportunity to start reforming this fishery.

Scott Carlson, Executive Director, Coastal Rivers Conservancy

CRC has been focused on reforming the Area 8 mixed stock fishery since its 2019 inception, following the lead of four Central Coast First Nations—the Nuxalk, Heiltsuk, Kitasoo Xais’xais, and Wuikinuxv.

“The Area 8 chum run overlaps with almost all other salmon that migrate through this region, from wild steelhead and Chinook to Kimsquit and Atnarko sockeye,” Carlson says. “That means this fishery intercepts other wild fish stocks critical to the area’s people, wildlife, and overall biodiversity.”

The Area 8 chum fishery has also been considered problematic by the lodge operators who serve the hundreds of steelheaders who flock annually to fish the Dean River.

“Steelhead depend on salmon-provided benefits throughout their life cycles,” says Carlson, a former fishing guide on the Dean. “But the future of both steelhead and salmon as species depends on us, and our ability to enact a more conservative fishing strategy for the Central Coast.”

Many of these intercepted stocks are already so vulnerable that commercial fishing for them ended years ago—and yet they continue to be caught in unknown quantities as bycatch in the Area 8 commercial chum fishery.

The future of both steelhead and salmon as species depends on us, and our ability to enact a more conservative fishing strategy for the Central Coast.

Scott Carlson, Executive Director, Coastal Rivers Conservancy

According to Dr. Atlas, effective fishery reforms start with better data to drive science-based management plans, as well as greater emphasis on selective fishing practices and new genetic tools like those currently under development by WSC, CRC, DFO, Simon Fraser University, and First Nations partners.

“The B.C. North and Central Coasts are home to hundreds of locally adapted populations,” Dr. Atlas says. “With genetic research, we’ll be able to assess the health of individual salmonid populations within watersheds, and eventually track specific run timing and migratory routes.”

Understanding species diversity at this level could help DFO, First Nations, and other fisheries managers plan fishing seasons with unprecedented precision, minimizing harm to nontarget species in mixed stock fisheries in B.C. and beyond. For now, many are still absorbing the Area 8 chum fishery closure, and the startling new data from Dr. Atlas’s team.

The rapid decline of Central Coast chum could read like one more bad headline, says Dr. Atlas. But he also sees the resulting fishery closure as a chance to change the way we’ve done business in the past.

“Taking our foot off the gas is the first step,” Dr. Atlas says. “Now we need to do the work of calibrating reforms to meet the fishery goals of the 21st century.”

The rapid decline of Central Coast chum could read like one more bad headline. But the resulting fishery closure is also a chance to change the way we’ve done business in the past.

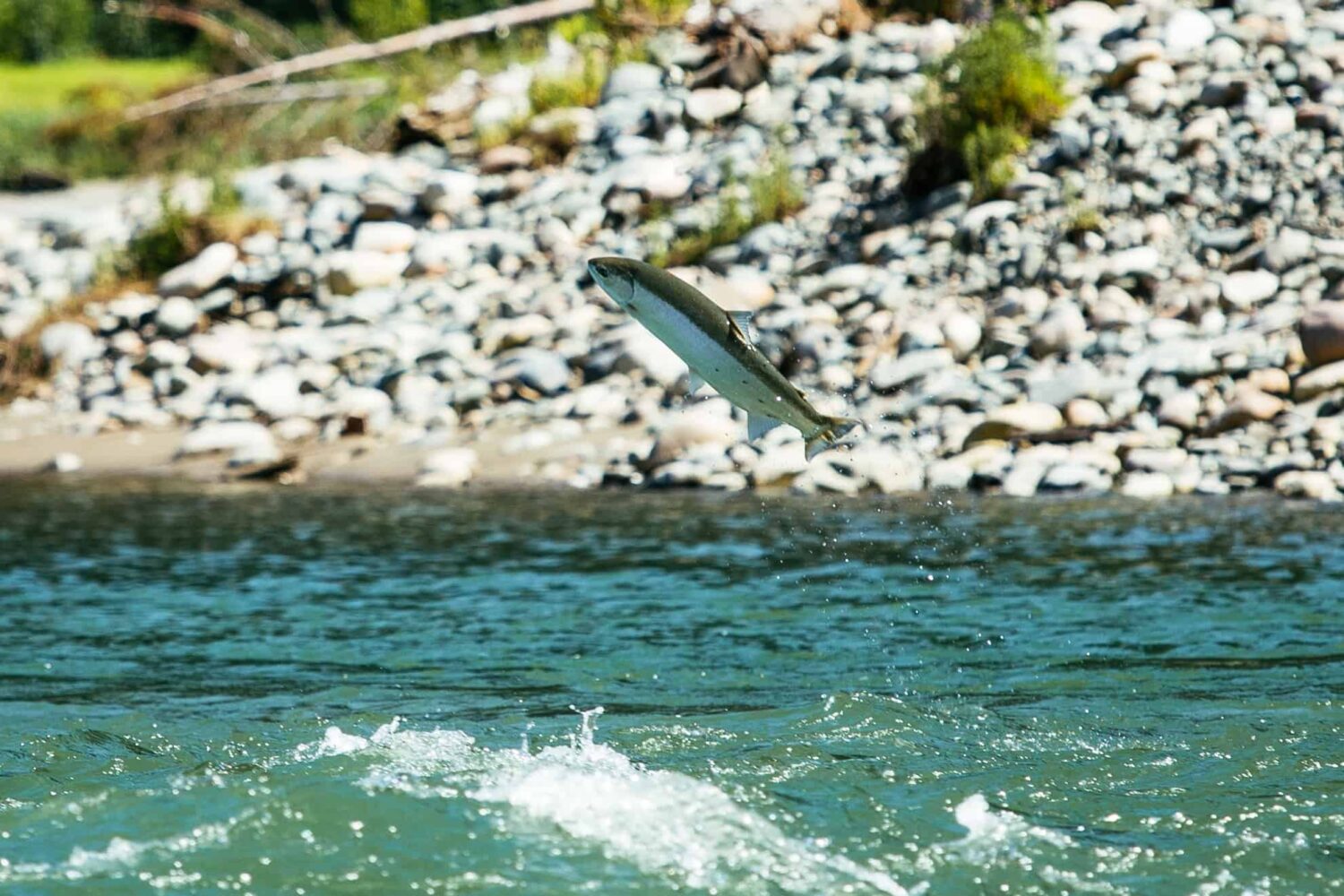

Hero Image