For the Tugur and Maia watersheds, new legal status could be a powerful tool to safeguard priceless biodiversity, including salmon and giant taimen.

The year: 2014. Guido Rahr, Wild Salmon Center’s President & CEO, was glued to the window of a helicopter, searching for his first glimpse of the Tugur, a remote, roadless river system 500 miles northeast of the city of Khabarovsk.

The Tugur had first come into focus more than a decade earlier, when Rahr and WSC supported an ambitious and urgent effort by Russian scientists, conservationists, and local government agencies to map the Russian Far East’s stronghold rivers and build a strategy to protect them.

Dr. Mikhail Skopets, a Russian scientist and longtime WSC partner, had floated the river to conduct a rapid biological assessment, and he reported a wild, untouched landscape that supported a highly productive ecosystem—one that included taimen, an enormous and mysterious freshwater trout. Now Rahr was seeing the Tugur for the first time, and realizing its true value.

“We flew over complete wilderness, vast expanses of peat bogs, mountain ranges, and meandering rivers,” he recalls. “When we got to the Tugur, we saw a labyrinth of tea-colored channels weaving in graceful turns through forests and wetlands.”

What Rahr and his travel companions encountered was a system that supported a level of bioproductivity largely lost in the Pacific Northwest. On the river, he spotted a surprising abundance of grayling, dimpling the surface like rain, huge numbers of lenok, and schools of Phoxinus minnows.

“There aren’t too many places like this on Earth,” he says. “These rivers are capable of growing salmonids that surpass 100 pounds, and they support amazing wildlife: Steller’s sea eagles, Blakiston’s fish owls, wolves, brown bears, moose, Manchurian elk, and dozens of other species.”

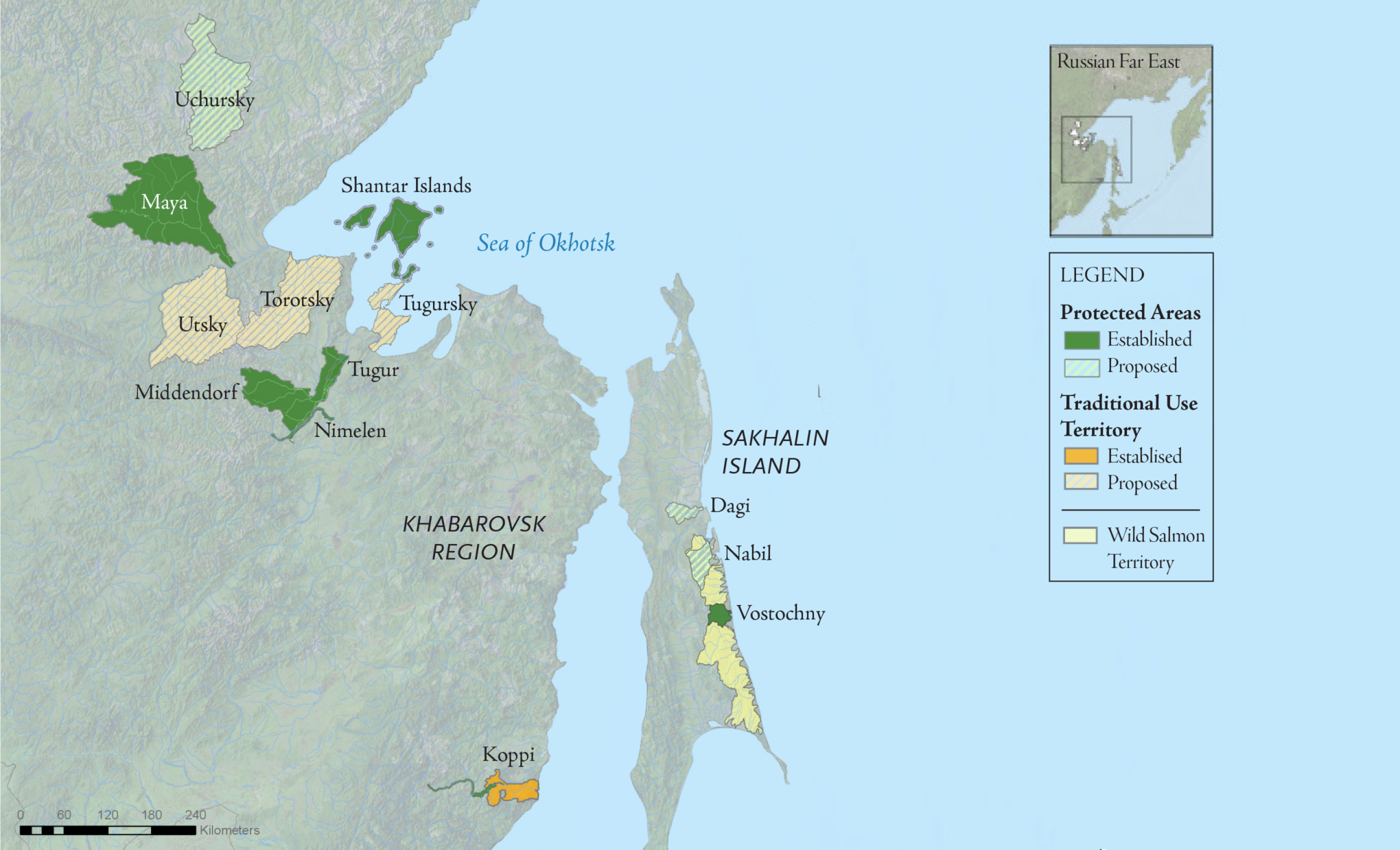

Last month, in a huge step forward for the stronghold protection strategy developed over the past two decades by partners including the Russian Academy of Sciences and regional fisheries agencies, the government of Khabarovsky-Krai officially created two massive new protected areas on the Tugur and Maia watersheds—a combined area of 3.7 million acres.

“There aren’t too many places like this on Earth,” Rahr says. “These rivers are capable of growing salmonids that surpass 100 pounds, and they support amazing wildlife.”

Together, the two reserves constitute an area roughly one-and-a-half times the size of Yellowstone National Park in the United States. The designations add to earlier successes by our Russian partners to protect places like the Kol River in Kamchatka, the Vengeri and Pursh-Pursh Rivers on Sakhalin Island, and the establishment of the Shantar Islands National Park just north of the Tugur in Khabarovsk.

According to Rahr, these combined protections are helping to act as a brake against expanding threats from logging, mining, and industrial development in the Russian Far East. In the Tugur alone, local conservation and fishing interests have battled new logging concessions and placer gold mining operations in recent years.

Key to the creation of the Tugursky and Maisky Reserves was WSC partner Alexander Kulikov, founder of the Khabarovsk Wildlife Foundation and an early partner in developing the plan for protecting Russian salmon strongholds.

For the past four years, Kulikov has shepherded the twin proposals through the approval process; convening scientists to prepare the biological justification for both reserves and liaising with the regional Ministry of Natural Resources and Ecology as well as many other regional agencies, Indigenous groups, fishers, and stakeholders.

“This is the most significant conservation achievement of our organization and our partners within the last eight years,” Kulikov says. “This designation has been the result of many years of effort by a large team of like-minded professionals supported by Wild Salmon Center.”

The newly designated Maisky Reserve safeguards two million acres of the tributaries and mainstem of the Maia River, the largest tributary of the Uda River. The Uda, like the Tugur, is an important salmon producer in the Russian Far East, and one of the last places where there are still giant taimen.

The 1.7-million-acre Tugursky Protected Area, named after A. F. Middendorf—a 19th century Russian explorer and zoologist—aims to protect 395 plant species, 47 species of mammals, 190 bird species, six amphibian species and 22 species of fish.

And with the new protections, these vast, intact, and pristine salmon ecosystems can also continue to act as some of the planet’s most effective carbon sinks, Rahr notes, making them vital tools in the fight against climate change.

“This is the most significant conservation achievement of our organization and our partners within the last eight years,” Kulikov says.

Home of the River Tigers

Across the Russian Far East, rivers like the Tugur and Maia are home to some of the largest and most charismatic creatures on earth. But to truly understand the uniqueness of these intact ecosystems, Rahr says we should look to the apex predator that lurks in their rivers: the giant Siberian taimen, a rare and ancient species of freshwater trout that can grow large enough to swallow adult salmon.

“Most of the world’s cold water rivers can only produce a trout of three to five pounds,” Rahr says. “On that first Tugur trip, I realized we needed to understand two things: why was this river so productive that it could grow taimen to reach this size? And how we could work with our Russian partners to better protect these rivers from the logging and mining efforts that would soon come?”

To answer these questions, Rahr has worked with Dr. Skopets, prominent Russian investor and WSC board member Ilya Sherbovich, international scientists including WSC Science Director Dr. Matt Sloat, and Russian businessman Alexander Abramov—the owner of a sportfishing lodge on the Tugur—to drive a series of new science and conservation projects on the Tugur.

One project has introduced a system to photograph, measure, and collect scale and tissue samples from each taimen caught by sport fishers in the Tugur: data that is helping scientists better understand taimen’s unique life history.

Over time, this growing body of research has made it clear that the unusual size of taimen stems from the Tugur’s surprising biodiversity, which supports the fish’s early diet that spans rodents, waterfowl, and fish species like grayling, lenok, and Amur pike. When taimen grow large enough, approximately 40 pounds in size, that diet scales up to include adult chum salmon, swallowed whole.

“We needed to understand two things,” Rahr says. “Why was this river so productive that it could grow taimen to reach this size? And how we could work with our Russian partners to better protect these rivers?”

For fly fishermen, the Tugur has become a sort of Shangri-La. Massive taimen caught on the river have won a recent cover in FlyFisherman magazine, as well as the rapt attention of fly fishers across the globe.

In the Fall 2016 issue of The Drake, Rahr detailed the challenge of catching giant taimen on a fly—a technique that few had tried and none had yet mastered on the Tugur. Rahr, Sherbovich, and Dr. Skopets are among those now developing new techniques to catch Tugur giant taimen on the fly, with Sherbovich currently holding the world angling record for taimen—and the entire salmonid family—caught and released on the Tugur.

Rise of Conservation Angling

The fishing potential of the rivers, combined with the wildlife protections afforded by the new reserves, present opportunities to boost the regional economy by enhancing catch-and-release ecotourism in the region.

The practice of catch-and-release has active and growing support from prominent national groups including the Russian Salmon Association, which has in recent years launched a nationwide campaign to expand conservation-minded angling in Russia. Already, international anglers beat a steady path to prominent fishing locations in Kamchatka—where, since the late 1990s, WSC has teamed with local guides to cultivate fly fishing tourism.

According to Gennady Zharkov, the Moscow-based advisory board chairman of the Russian Salmon Association, the recent Khabarovsk designations give organizations like RSA important new tools to expand salmon conservation and ecotourism work in Russia.

“I strongly believe that the more protected areas of all kinds we can create, the better,” Zharkov says.

Critically, the reserves also strengthen fishing and hunting opportunities for the region’s Indigenous communities, says WSC Western Pacific Director Mariusz Wroblewski.

“Protecting these areas is a way to secure not only their biodiversity, but also their priceless benefits for people near and far,” Wroblewski says. “And it can inspire communities elsewhere looking to safeguard Indigenous rights and livelihoods based on land use and fishing.”

According to Rahr, Khabarovsk’s new protected areas could have even greater reach: potentially capturing public imagination worldwide, and shaping regional identity at home.

“Salmon conservation in the Russian Far East is at an inflection point,” Rahr says. “These rivers aren’t yet degraded by development, but without protection, they will be. And the opportunities to secure them at this scale will only grow more scarce. We cheer the government of Khabarovsk for this farsighted move, and hope they’ll add more of these extraordinary rivers to their protected area network.”

“Salmon conservation in the Russian Far East is at an inflection point,” Rahr says. “These rivers aren’t yet degraded by development, but without protection, they will be. And the opportunities to secure them at this scale will only grow more scarce.”