Steelhead Season: Is this our moment to get it right for an extraordinary—and imperiled—species?

Part I, in the Heart of Steel story series | Part II | Part III

By Ramona DeNies

For as long as there have been Quileute people on the remote, rugged Olympic Coast, returning steelhead have signaled the end of what’s called “bad weather season,” and the beginning of fishing. In the Quileute language, early winter is literally known as “steelhead season.”

Some try to map the solar calendar onto this cycle, and peg steelhead season to a specific month. But that shifts the focus to Western ways of knowing, rather than the ancient bond between steelhead and the first people of the Pacific Northwest.

“Fish, to us, it goes way back,” says Ann Penn-Charles, a member of the Quileute Tribe of the Quillayute River basin, prevention specialist, and teacher of the Quileute language. “If you took the fish away from the people, the people wouldn’t be able to feed their spirit. Fish are the heart of it.”

For Miss Ann, as she is known in the Quileute village of La Push, there isn’t a way to separate salmon and steelhead from the story of her family, her community, her history.

There is her father, Christian “Jiggs” Penn, Jr., a fisherman, Korean War veteran, and lifelong advocate for Tribal fishing rights. And her grandmother, Lillian Payne Penn Pullen, who passed on the traditions of fish-handling, processing, and community spirit.

The story goes back farther, to her great great grandfather, one of the Quileute leaders who participated in the Treaty of Olympia in 1865. In this treaty, the United States government acknowledged the perpetual right of the Quileute people to hunt, fish, and gather in all “usual and accustomed places”—even as it sought to restrict Tribal members to a tiny reservation at the mouth of the Quillayute River.

In 1974, Miss Ann’s father was the Quileute Tribe’s representative in U.S. vs. State of Washington, a landmark case led by Federal Judge George Boldt. Her father’s testimony, alongside dozens of other witnesses, convinced the judge to reaffirm treaty rights following more than a century of broken promises, harassment, disenfranchisement, and violent, capricious policing by non-Tribal authorities. In his ruling, Judge Boldt agreed with the plaintiffs that the Treaty of Olympia enshrined the right of signatory Tribes to co-manage fisheries across their traditional homelands.

In the five decades since the Boldt Decision remade Washington fisheries, Tribal, state, and federal agencies are still negotiating paths through these waters. Resource co-management is painstaking work, made harder by the weight of history.

Miss Ann is proud of what Quileute fisheries managers are doing to nurture the salmon and steelhead that return each year to the Quillayute River—from water temperature monitoring to natural infrastructure projects that aim to protect La Push while enhancing fish habitat.

She’s keeping an eye on this work herself, monitoring new streamside replantings on her walks to collect items for medicine. And she enjoys hearing from fishers where salmon are showing up—especially if these are spots where her parents once were caretakers.

“As my father would paddle home with a canoe full of fish, he’d check certain areas to see how many fish were in the creeks,” Miss Ann recalls. “He’d get brush and put it along the banks, where he knew fish would spawn. My grandfather taught my father to heed all of the things taught to him. It takes all of us to be stewards of the land.”

The reward of good stewardship is health. For millennia, the flash of steelhead in rivers brightened the winters of the Quileute people—a sign of a thriving relationship. Now, with Indigenous leadership resurgent in fisheries management, Tribes and First Nations are reclaiming traditional spaces for hunting, foraging, and fishing, and their role as primary stewards.

But as the Quileute Tribe finally sees respect for sovereignty on land and water, something else has gone wrong. The steelhead are disappearing.

“If you took the fish away from the people, the people wouldn’t be able to feed their spirit. Fish are the heart of it.”

Ann Penn-Charles

Lillian Payne Penn Pullen loved steelhead, particularly smoked. Miss Ann remembers that about her grandmother, as well as her lessons on using all parts of the fish.

Dwayne Pecosky, the Director of Quileute Natural Resources, also loves steelhead. That’s because along with his day job managing Tribal fisheries and restoration work—including an ambitious river rewilding project with Wild Salmon Center and other partners—he’s also an avid angler.

“It’s a special thing, seeing winter chrome come into the Quillayute Basin,” Pecosky says. “Steelhead are hard to catch. They call it the ‘fish of a thousand casts’—that’s the saying, but maybe I know it because I don’t catch a lot.”

Pecosky laughs, and acknowledges that for him, it’s not really about catching fish. It’s enough just to float on a rainy winter day and know that steelhead are out there.

“You’re talking to a person who knows how amazing steelhead are in their behavior, their life history,” he says. “It’s incredible to be able to touch a winter steelhead and realize that it might have made it home, went back out to the ocean, jumped through all these hoops, and made it back home again.”

“It’s incredible to be able to touch a winter steelhead and realize that it jumped through all these hoops, and made it back home again.”

Dwayne Pecosky, Quileute Natural Resources Director

Unfortunately, steelhead are scarce in smokehouses these days. Instead, the Quileute Tribe is watching with concern as steelhead numbers drop, year after year.

“We know we’re doing the right things, and we’ll always put an emphasis on conserving for future generations,” Pecosky says. “The Tribe is doing what it can on the lower Quillayute, aiming to manage its fisheries with a meticulous eye.”

The Tribe is worried enough that it’s taking drastic conservation measures—a reaction echoed in recent emergency rules adopted by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW). In recent years, the co-managers have responded to low steelhead forecasts with a suite of seasonal actions for the recreational fishery, including mandatory catch-and-release and bans on bait fishing and fishing from boats. In 2020 and 2021, the Quileute and other Washington Coast Tribes voluntarily reduced steelhead fishing days by more than half.

When decisions are made to cut back fishing days, Pecosky says it’s important to remember that’s a very big deal for the community.

“We’re salmon people and fishing is a way of life for the Quileute Tribe,” he adds. “When a Tribe shuts down their treaty fishery, that’s instrumental in demonstrating the conservation concern.”

In 2022, with steelhead forecasts again looking dire, coastal Tribes volunteered once more to reduce fishing days. Meanwhile, WDFW announced early steps to overhaul its steelhead management strategy entirely. The era of complacent fisheries management was over. Now, agencies—and fishers—need answers.

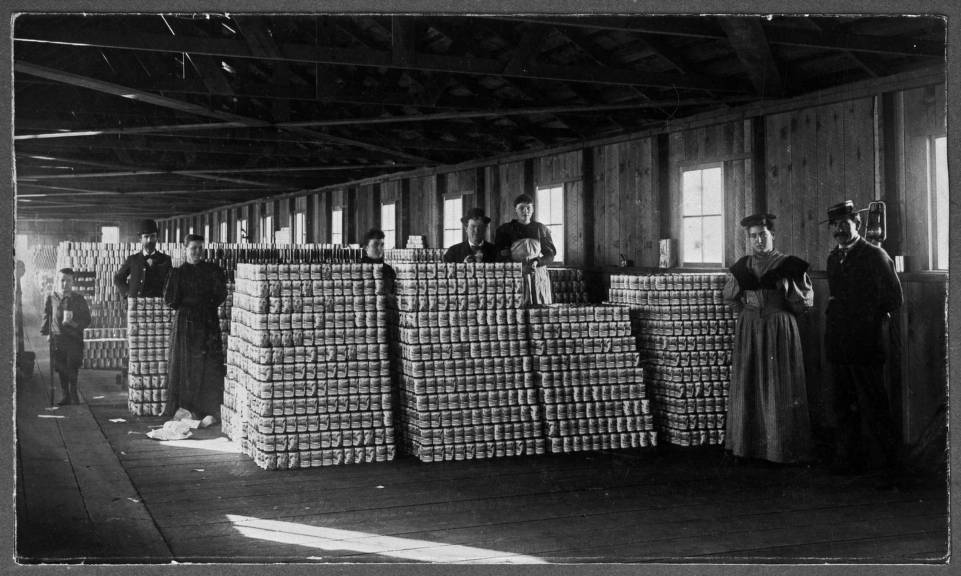

Up and down the Washington Coast, there’s no doubt that steelhead are in trouble. New research from Wild Salmon Center and our partners shows that steelhead have been in decline for decades—and perhaps more than a century, since the introduction of canneries, commercial fishing, logging, mining, and other ecosystem-altering practices.

These insights might seem obvious, in hindsight. But for Pacific Northwest fisheries managers, it hasn’t been easy to see the big picture. For these agencies, the earliest reliable steelhead spawning records date back just 40 years, to the early 1980s soon after the Boldt Decision.

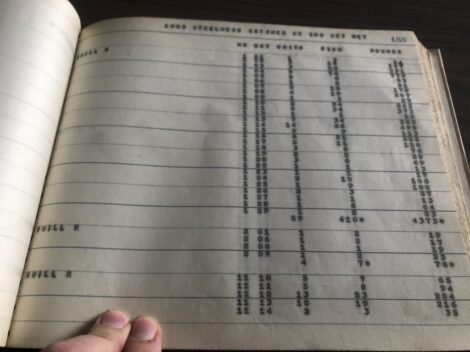

Last year, one humble discovery showed us the bigger picture. Thanks to a team of scientists including WSC Director Dr. Matt Sloat, we can now track Olympic Peninsula steelhead to the late 1940s. What the data reveals is raising alarm bells all the way east to Washington, D.C.

Up and down the Washington Coast, there’s no doubt that steelhead are in trouble. Now, agencies—and fishers—need answers.

The discovery—a single dusty ledger in an Olympia office—didn’t look like much. But for Dr. Sloat and scientists from Trout Unlimited and NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Office, the ledger’s data unlocked a world of insights. Starting with the vast chasm between what steelhead runs might have looked like for Miss Ann’s father, as a young man in the 1950s, and what they are today.

“Olympic Peninsula steelhead are at a fraction of their historical abundance,” Dr. Sloat says. “Until now, we weren’t able to fully appreciate that loss, because our frame of reference only went back a few decades.”

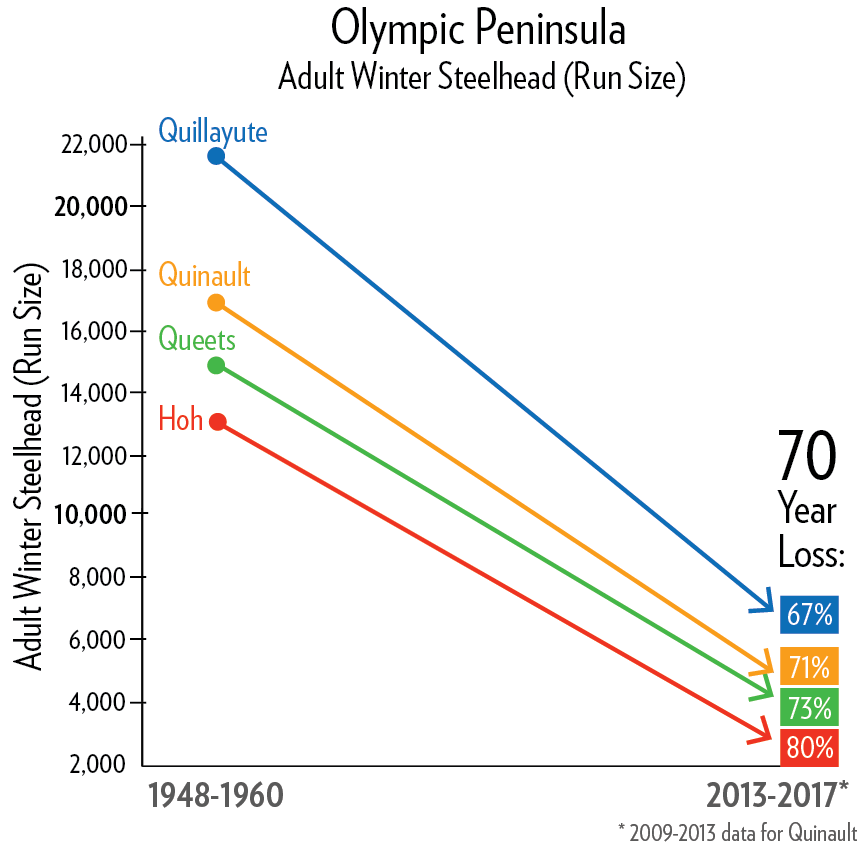

The team found that between 1948 and 2017, wild winter steelhead numbers plummeted by at least 67 percent in the Quillayute River. In the neighboring Hoh, Queets, and Quinault systems, the rates were 80, 73, and 71 percent respectively. According to Dr. Sloat, the most recent data suggest that decline rates are accelerating.

Why are steelhead in such trouble? To answer that, Dr. Sloat and his colleagues are investigating a range of potential factors including ocean warming, hatcheries, and habitat loss. Recent breakthroughs in conservation genetics are revolutionizing this work, he says, enabling us to better grasp the steelhead biodiversity that so amazes anglers like Dwayne Pecosky.

“For millions of years, steelhead have drawn on a range of life histories and behaviors to survive,” he says. “We’re just now beginning to understand what’s in that genetic toolkit.”

One of those tools is a drive within some steelhead to return months ahead of their fellows. These are the first freshwater arrivals in the height of winter—those heralds of fishing season for the Quileute people. But across the Olympic Peninsula, steelhead runs are losing their vanguard: a clue that somehow, critical biodiversity is getting lost.

Across the Olympic Peninsula, steelhead runs are losing their vanguard: a clue that somehow, critical biodiversity is getting lost.

“These early returners are simply not there anymore,” Dr. Sloat says. “This fact alone might shed some light on why it feels like steelhead are vanishing in plain sight.”

If we can learn why early returners are disappearing, he says that insight could help conservation scientists and fisheries managers develop powerful new recovery strategies. But good science takes time and resources. Meanwhile, for steelhead, the clock is ticking.

That’s why Dr. Sloat isn’t surprised that NOAA Fisheries is now considering the most dramatic move of all: listing Olympic Peninsula steelhead under the Endangered Species Act.

This winter, NOAA announced a 90-day review period, the first step in its formal review process. Should the process move forward to public comments, rulemaking, and a final decision, more sacrifices could be ahead—both for the sport fishers who flock to the Olympic Peninsula, and for Tribes like the Quileute. ESA listing could mean yet another renegotiation of fisheries co-management: an exhausting prospect for all involved.

But while ESA listing would add complexity, it could also unlock a new level of resources for Tribal and state fisheries managers: perhaps enough to pivot away from crisis mode, and toward a consensus-driven, science-based approach to long-term conservation.

“Sound science is key to getting steelhead recovery right,” Dr. Sloat says. “Because no solution that we come up with will work without everyone agreeing on the facts and pulling in the same direction.”

NOAA Fisheries is now considering the most dramatic move of all: listing Olympic Peninsula steelhead under the Endangered Species Act.

Can we save steelhead? From La Push to Olympia to Washington, D.C., many are skeptical. When it comes to this priceless fish, our history is a fraught one. And conditions today aren’t necessarily different. Across the Pacific Northwest, and beyond, different fishing factions are often more comfortable pointing fingers than finding common ground.

No one knows this history better than Miss Ann. And she thinks it’s high time we learn from it.

“We have to work together—sport and Tribal fishers, Washington State, everyone—to make sure that the mistakes of the past don’t happen in the future,” she says. “It will take all of us to make sure that our salmon and steelhead are here for the next seven generations.”

“We have to work together. It will take all of us to make sure that our salmon and steelhead are here for the next seven generations.”

Ann Penn-Charles