The Makah Tribe has cleaned up after the U.S. military for decades. A partnership with Wild Salmon Center could speed this work for salmon.

One sunny August afternoon in 2024, two fish ecologists dipped hands in a small creek framed in tall beach grass. In an eddy, finger-length wild fish darted through the clear water—coho salmon, the ecologists marveled, or possibly steelhead or cutthroat trout.

At this early stage of life, it can be hard to distinguish these wild fish species without closer inspection. But despite their tiny size, it was clear that these adventurous young fish weren’t afraid to taste salt. They tested the water just yards from where tiny Wa’atch Creek meets the Pacific Ocean, following its short, steep descent through Olympic Peninsula rainforest.

From Seattle, the nearest major city, it takes more than four hours by car to get to this craggy beach. This is Makah Territory, and Makah Tribal Habitat Division Manager Stephanie Peterson Martin is responsible for stewarding the health of fish and wildlife across all 54 square miles of this sovereign nation at the northwesternmost corner of the contiguous United States. Now, thanks in part to Peterson Martin’s guest that afternoon—Wild Salmon Center Fish Habitat Specialist Nicole Rasmussen—she and her team will bring that focus on fish directly to Wa’atch Creek.

“When Nicole approached me about projects, it’s like, man, I got this whole list!” Peterson Martin recalls. “I said, I could keep you guys busy for a long time. But let’s start with one.”

“When Nicole approached me about projects, I said, I could keep you guys busy for a long time. But let’s start with one.”

Makah Tribal Habitat Division Manager Stephanie Peterson Martin

Wa’atch Creek runs more than seven miles from headwaters to ocean. But for the young fish darting in the summer eddy, it’s much, much shorter. Just a quarter-mile upstream, these fish meet a formidable relic from World War II: a squared-off tunnel that looks more like a hallway for humans than a route for small fish.

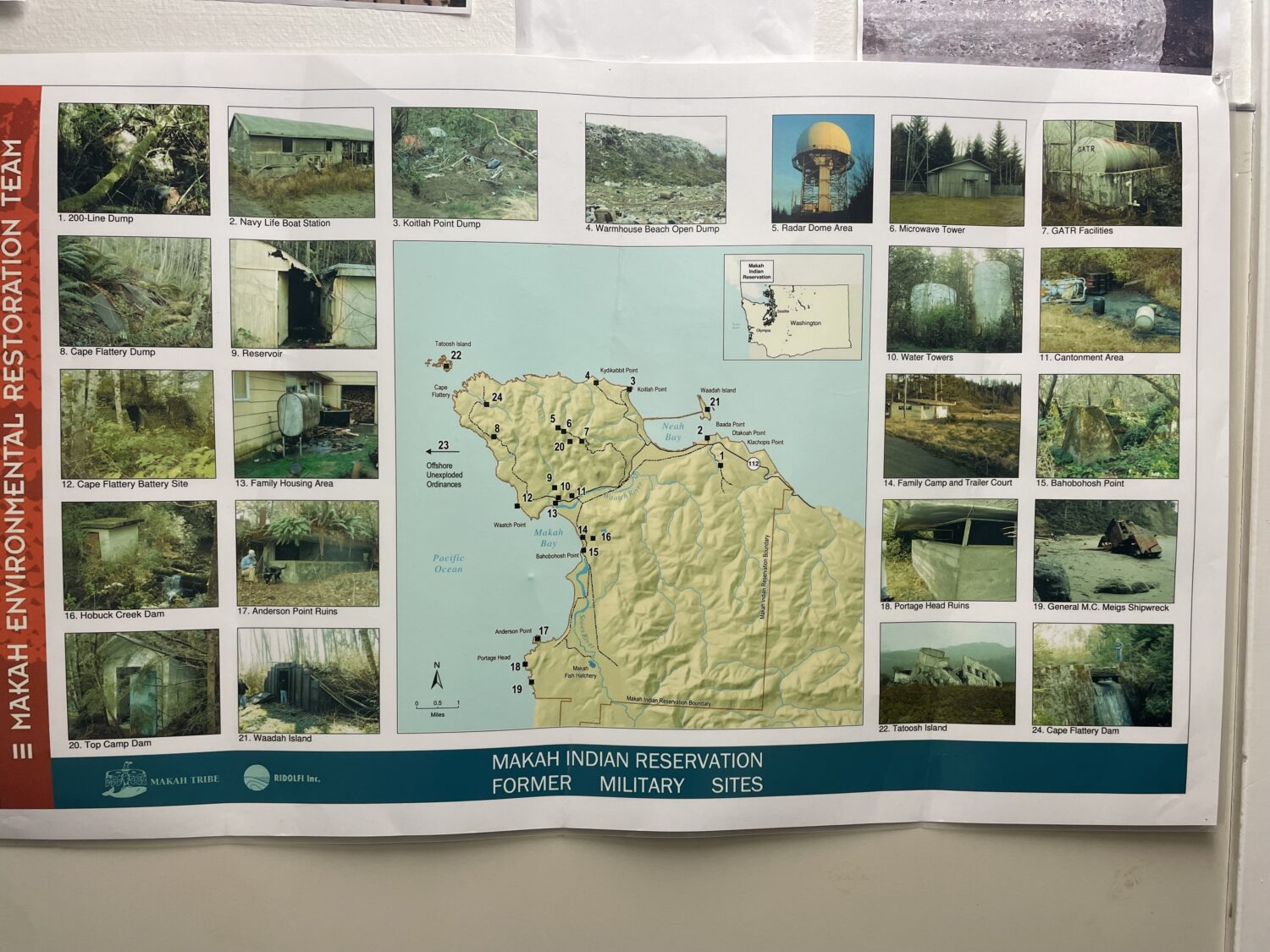

World War II was a particularly fraught period of history for the Makah. In the early 1940s, during wartime heights, the U.S. Army abruptly commandeered strategic locations across Makah Territory—building roads, radar stations, office compounds, and myriad other heavy infrastructure.

The presence of U.S. armed forces didn’t end with the war; it wasn’t until 1988 that the U.S. Air Force finally withdrew its last stationed personnel. To this day, Makah Tribal experts are still working to clean up military debris—from asbestos siding to a warren of old, cracking water pipes, soil contaminated by leaky underground fuel storage tanks, garbage dumps, and even shipwrecks.

The military aftermath includes the Wa’atch Creek box culvert: a massive concrete tunnel installed by the Army when it paved Cape Flattery Road around the peninsula’s most remote corner. The culvert—squared on all sides and 30 feet long—turns into a firehose in the winter: shunting water through too fast for fish to navigate. In summer, the culvert’s flat floor spreads the flow fingernail-thin across the concrete: much too low and slow for fish.

To this day, Makah Tribal experts are still working to clean up military debris—from asbestos siding to a warren of old, cracking water pipes, soil contaminated by leaky underground fuel storage tanks, garbage dumps, and even shipwrecks.

For the Makah, the problems here don’t end with fish passage. A beach ball-sized dip in the road above offers clear evidence that the box culvert is also starting to fail structurally, taking the road with it. It’s a “ticking time bomb,” says Peterson Martin, with serious consequences for her community. Cape Flattery Road is the first Tribally-owned scenic byway in the United States, and essential to the Makah’s growing tourism economy. It’s also a key evacuation route for Tribal members in the event of a tsunami.

All of this makes fixing Wa’atch Creek’s box culvert a top priority. But for years, this work has felt logistically out of reach. Work on Cape Flattery Road is subject to a morass of conflicting federal and state road standards. There are funding issues, and permitting and labor constraints. But Peterson Martin knew of Wild Salmon Center’s success in partnering with Washington Coast Tribes to find federal salmon recovery dollars for critical infrastructure projects. Why not try out a partnership, she thought—test the saltwater a bit, like those baby fish?

“I knew that Wild Salmon Center has approval to work here,” Peterson Martin says. “So the question is, can we get it done?”

From summer 2024 and into fall, plans evolved from conceptual to concrete. The two teams worked out a timeline that spanned initial design to boots-on-ground construction. Rasmussen tapped her Wild Salmon Center colleagues to help secure grant funding for initial project designs from the Resources Legacy Fund Open Rivers Fund and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“I knew that Wild Salmon Center has approval to work here. So the question is, can we get it done?”

Makah Tribal Habitat Division Manager Stephanie Peterson Martin

In December 2024, Rasmussen and Peterson Martin bushwhacked down to the banks of Wa’atch Creek with Tribal staff and KPFF engineers. The field visit formally kicked off plans for replacing the concrete box culvert with an arched and far wider steel bridge span. By this summer, Tribal and Wild Salmon Center staff will review designs with engineers: designs that they can take back to agencies like NOAA to fund boots-on-ground construction.

Once full funding is secured, it will take three years, at least, to complete the Wa’atch Creek Project. Tourists taking camper vans to the Cape Flattery Trail and lighthouse overlook will need to endure construction delays and detours, as crews repave a dip-free road on top of the new bridge. Peterson Martin and Rasmussen will also need to exercise patience, to see if Chinook salmon, coho, steelhead, and cutthroat trout eventually find their way under the new bridge to the upstream habitat the project will reopen.

Both ecologists know that for wild fish, every new mile counts. Research shows that small creeks like Wa’atch can play an outsized role in the long-term resilience of salmon and trout in the Pacific Northwest and beyond. Each new stretch of cold, clean water gives wild fish more room to adapt and thrive in a time of rapid climate change.

“If this project is successful, I think it opens up the door for conversations about other projects that we also need,” Peterson Martin says. “So we are super excited about this partnership.”

Already, she and Rasmussen are scoping out other fish passage projects across Makah Territory. Many of them are barriers created by World War II’s military buildout and the long federal presence that followed. Project by project, the Makah are reclaiming their land from this unwelcomed legacy. Project by project, they’ll also be welcoming more salmon home.

“If this project is successful, I think it opens up the door for conversations about other projects that we also need. So we are super excited about this partnership.”

Makah Tribal Habitat Division Manager Stephanie Peterson Martin