Impacts linger from the Blob, keeping Chinook counts low. But ocean conditions look to be improving.

Sea surface conditions in the Pacific have cooled this spring. And that’s a welcome change from the stagnant ocean phenomenon from 2014 to 2017 dubbed The Blob, which significantly impacted Chinook salmon size and numbers. In coming years, so long as healthier ocean conditions prevail, we could see greater returns and healthier fish.

But Chinook returns will still lag in 2019.

This is the final year in which Chinook that grew up in the poor conditions of The Blob will return to spawn. Most experts expect counts to be low and early returns are following the predictions.

“One of the big concerns in 2017 was that we caught very few Chinook and Coho in the ocean,” said Laurie Weitkamp, a Research Fisheries Biologist with NOAA Fisheries. “The numbers were almost our lowest ever. And those fish are starting to return this year.”

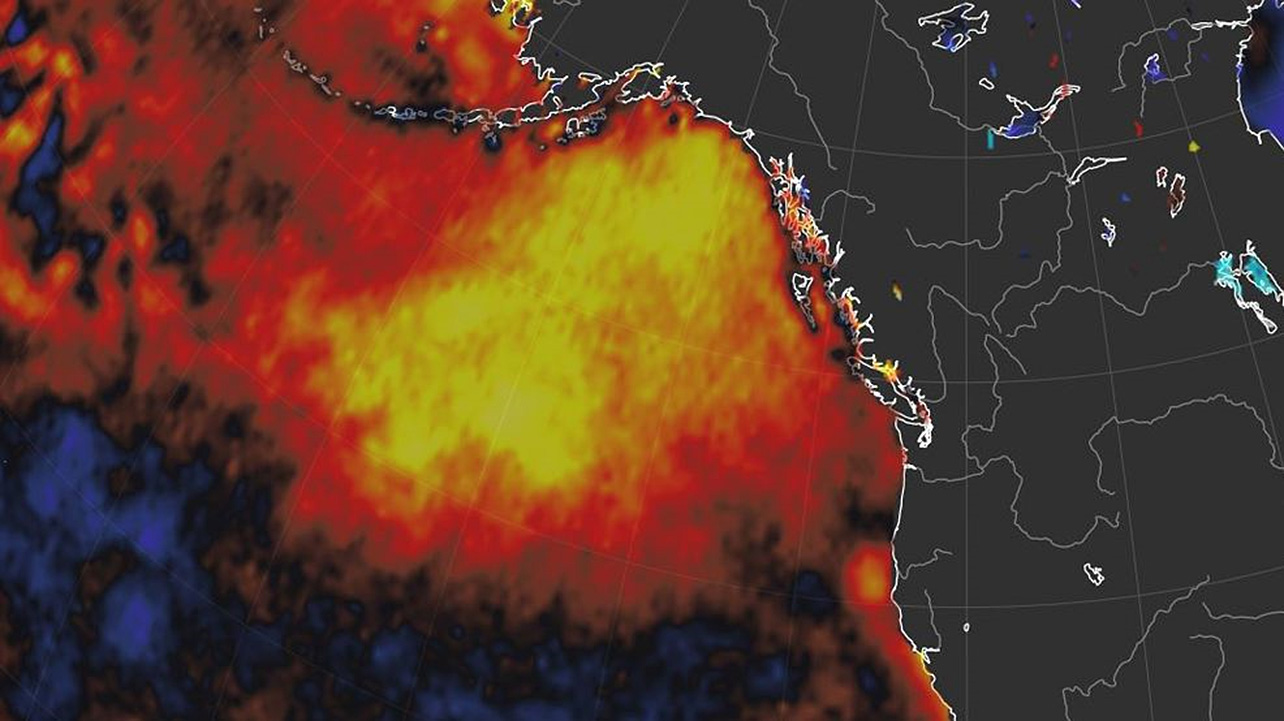

The Blob in the north Pacific, which stretched from the Gulf of Alaska down to Canada and the Pacific Northwest, formed during a marine heat wave that shut down a process called vertical mixing. Vertical mixing, propelled by winters storms on the Jet Stream, stirs ocean water and pulls cold water up from the ocean depths. The process stirs nutrients through the water column and pulls more oxygen into the water.

“Vertical mixing brings a lot of nutrients to the area,” said Matt Sloat, director of science at Wild Salmon Center. “And it feeds the base of the food web. Water temperatures can greatly impact the type of food that salmon have available.”

In 2014-2017 that mixing phenomenon became stagnant, disrupting the food web that supports juvenile Chinook and Coho salmon. It led to undernourished and underdeveloped fish. Coho, which take about 18 months to grow in the ocean and return to spawn, are less impacted by the phenomenon this season because they grew up in post-Blob conditions. But Chinook, which take about four years, are still feeling the impact, and the last generation of Chinook that lived through the phenomenon will return this year.

“There are some light signs of Coho recovery, but Chinook aren’t expected to be as abundant.” Sloat said.

The Columbia River gives us some indication of Chinook returns. By April 13-14, just 184 Chinook had crossed Bonneville Dam, a tiny 9 percent of the 10-year average of 2,027 fish. It was the eighth lowest return for those days in the past ten years. A run of 99,300 up-river spring Chinook are expected this season, which is 86 percent of last year’s run of 115,081 fish and half the 10-year average of 198,200 fish, but experts are warning it could be even lower.

Ocean conditions also aren’t likely to return to their old norms as climate change continues. Last summer, Oregon waters experienced stagnant areas and some acidification, despite things being a bit cooler. And in 2019, we may see the same phenomenon, said Scientist Toby Garfield, who monitors ocean conditions at the Southwest Fishery Science Center.

“Last summer, the Oregon coast experienced both some hypoxia and some ocean acidification,” Garfield said. “The models are suggesting that could occur again this summer.”

A weak El Nino appears to be forming at the equator this season, which could lead to up to 2 degrees Celsius of warming in the summer, Weitkamp added.

“Around here in the Pacific Northwest if you get warmer temperatures, it’s not good for salmon,” Weitkamp said. “If you’re in Alaska, that’s a little more benefit.”

As cold water fish, salmon prefer cold water prey species, such as herring, anchovies and small crustaceans. As the climate has continued to warm, salmon are moving further north, with populations growing in Alaska even as they shrink in the Pacific Northwest.

“They’re certainly seeing expansion of salmon up to the arctic,” Weitkamp said. “And there’s a lot of concern about mixing of Pacific and Atlantic salmon through the arctic.”

The jet stream and other phenomenon that impact ocean temperatures are also expected to remain erratic as the globe continues to warm.

“Things aren’t back to normal in a lot of respects.” Weitkamp said. “For one thing, squid populations have taken off. There are commercial fisheries harvesting them now, but it’s a sign of an unhealthy ocean.”

Squid populations have been slowly increasing over the past 10 years, and they outcompete other species that salmon live on, she noted.

“Squid are opportunists, they prosper where they can,” Weitkamp said. “Last spring was the highest squid catches off the coast ever.”

Other signs that the oceans aren’t healthy include sightings of tropical fish in Oregon, sharks in British Columbia and low Pacific Cod abundance. And Weitkamp said that due to climate change, it’s unlikely that we’ll see oceans return to prior norms anytime soon.

“I doubt it,” Weitkamp said. “I think we’ll have some normal years, but I think the extreme years will get even more extreme.”

It will take global action to fight the larger impacts of climate change, but there are some local things people can do to help salmon recover. Most of that is related to land use, Sloat said. Runoff from farms and poor forestry practices lead to warming temperatures, diversion and disruption of stream flows, and increased sediment in streams where salmon spawn, reducing their odds of survival when they reach the ocean. But anglers and residents can work to protect streams from disruption through preservation efforts or smarter regulation.

“If we can help the salmon be better prepared in fresh water, they’ll be better prepared to survive in salt water when they get there,” Sloat said. “There are lots of things people can do related to land use.”

Hero Image