A unique Wild Salmon Center-supported pilot program teaches fifth graders how salmon are key to healthy ecosystems, economics, and communities.

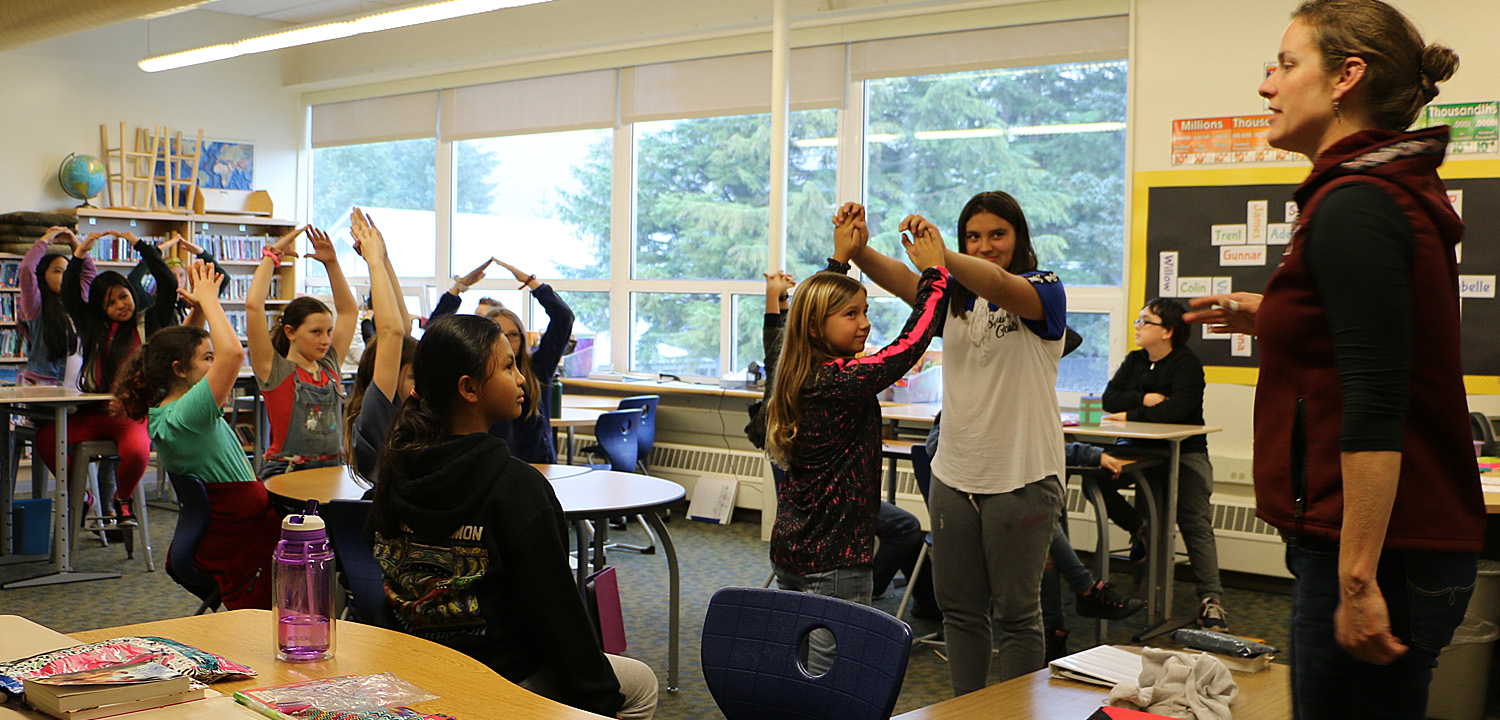

Kate Morse is holding the attention of a roomful of schoolchildren, right until a flock of migrating Sandhill cranes swoops by and everyone heads to the window. When the cranes recede from view, the noses come off the glass, and Morse skillfully pivots back to her lesson.

“So, why can’t we see the cranes all the way to Yakutat?” she asks. “What’s in the way?”

“Mountains!” shriek the fifth graders in Mrs. Carpenter’s class at Mt Eccles Elementary in Cordova, Alaska.

Mountains are a great segue into this week’s lesson on watersheds. Morse tells each student to crumple a page of paper and outline the “ridgelines” in blue marker—ink that bleeds, when sprayed with water, downhill into rivulets and pools. Consider how water tumbles down the mountains surrounding Cordova, flowing into the Copper River and Prince William Sound just blocks away, and the relevance of this exercise becomes crystal clear to these 24 kids.

It’s early September: week one of a unique year-long pilot science program co-developed by the Wild Salmon Center, Prince William Sound Science Center, and the Copper River Watershed Project. Over lessons spanning several months in fall and spring, these students will learn about food chains and river hydrology, and trace the fish forward to the human families they support.

“Salmon is the red thread that holds the program together,” says Morse, who runs the pilot as CRWP’s program director. Morse has honed the lesson plan since it launched here in 2016; sometimes she tests out new activities herself, like today. All the tweaking and honing, she says, is in hopes of eventually rolling out this curriculum to other schools—in Alaska, and perhaps beyond.

“Teachers want help to meet their required standards: science, math, research skills,” says Morse. “We connect that learning to the community where students live.”

Where other salmon-focused educational programs focus on just ecology (like one developed by the State of Alaska, which mostly sticks to salmonid life cycles), the WSC-funded curriculum encompasses science, economics, and cultural history. Morse’s lessons are highly interactive, and also, she thinks, pretty fun; in the second class, students “become” a watershed via role-playing. Later, there are scavenger hunts and games of Salmonopoly. Twice a year, the lessons get really real on field trips: the kids get on boats with commercial fisherman, and wade into spawning streams, surrounded by salmon carcasses, where they map the actual ridgelines around them. (Ask the sixth graders in Krysta Williams’s class what they remember from last year, and you get many shout-outs for those field trips.)

“Research shows that when you make learning relevant to students’ lives, more personal, they retain more,” says Morse. “The goal is, if we can communicate the watershed needs of salmon, and its role in the community, then they’ll be active stewards, and hopefully share this message with their families.”

The goal is, if we can communicate the watershed needs of salmon, and its role in the community, then they’ll be active stewards, and hopefully share this message with their families.”

Hero Image