A resource extraction challenge to so-called “D-1” lands gives us a chance to make a powerful—and historic—conservation countermove.

In Alaska, everything is bigger. That includes a historic opportunity to protect huge tracts of public land in a state teeming with wild salmon streams.

Since January 2021, we’ve been working with our partners to stop five Public Land Orders prepared by the Secretary of the Interior under the Trump Administration. The orders would open up some 28 million acres of public lands and waters to extractive industrial development. (See these 5 maps that help tell the story.)

The salmon- and wildlife-rich federal lands named in the orders are located in the Bristol Bay, Bering Sea Western Interior, East Alaska, Kobuk Seward, and the Ring of Fire regions.

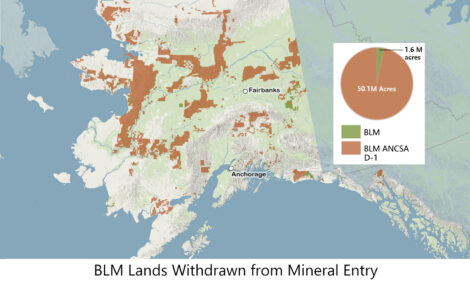

Known as “D-1” lands, these acres have been considered off-limits to mineral, oil, and gas extraction since the passage of the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

Alaska’s BLM-managed D-1 lands cover roughly 13 percent of the state: unfragmented habitat that represents some of the nation’s largest remaining intact ecosystems.

Alaska’s BLM-managed D-1 lands (50.1 million acres in total) cover roughly 13 percent of the state. These large swaths of unfragmented habitat represent some of the nation’s largest remaining intact ecosystems, from high alpine tundra to the pristine estuaries and wetlands in places like Bristol Bay, home to the world’s most abundant wild sockeye runs.

These landscapes support migratory birds and roving herds of caribou, while their undisturbed watersheds deliver the cold, clean water that wild fish need to weather accelerating climate impacts. For Alaska Native communities that rely on subsistence fishing and hunting, D-1 lands are critical to supporting food security and maintaining a way of life that has endured for millennia.

“So far, the D-1 protection still remains in place,” says Wild Salmon Center Alaska Program Director Emily Anderson. “And this protection is arguably more important than ever, given the pressures of climate change on Alaska’s natural systems, fish and wildlife populations, and human communities.”

“D-1 protection is arguably more important than ever, given the pressures of climate change on Alaska’s natural systems, fish and wildlife populations, and human communities.”

WSC Alaska Program Director Emily Anderson

When Congress enacted ANCSA five decades ago, it expressly withdrew unreserved lands in Alaska to allow the Secretary of the Interior time to determine whether opening these lands to resource extraction served the public interest.

Now, the previous administration’s five Public Land Orders force the agency to make a decision. And with BLM’s ensuing environmental review process, launched this past summer, comes a chance for communities, hunters, anglers, and conservation groups to make the case that strong D-1 land protections—not resource extraction—best serve the public interest.

The opportunity to make a conservation case for 28 million acres is a unique one in the history of BLM land management in Alaska.

According to Anderson, this environmental review won’t be business as usual for BLM.

That’s because the agency is looking at the impact of extractive development across wide ranges of Alaska’s BLM lands—rather than siloing its review into narrower regional management plans. This broader perspective opens serious discussion on the value of unfragmented landscapes to high-value migratory species like salmon and caribou.

“It is incredibly hard to protect large landscapes,’ Anderson says. “So it’s huge that, for the first time, BLM is really looking at how land use decisions could impact large landscapes, fish and wildlife habitat, and cultural and subsistence resources beyond its standard lens.”

“For the first time, BLM is really looking at how land use decisions could impact large landscapes, fish and wildlife habitat, and cultural and subsistence resources beyond its standard lens.”

WSC Alaska Program Director Emily Anderson

In October, BLM wrapped up a scoping public comment period—the first step in the environmental review process. Next, Anderson expects that BLM will release a draft environmental impact statement in summer 2023, triggering a new opportunity for public comments in this process.

When that happens, Anderson says WSC and our partners will be ready to speak up loud and clear in support of keeping the D-1 protection.

“We absolutely cannot afford to pass up this historic opportunity to secure a huge win for Alaska’s fish, wildlife and human communities,” Anderson says. “What’s at stake here is no less than the future of some of our last, best undisturbed public lands.”

“We absolutely cannot afford to pass up this historic opportunity to secure a huge win for Alaska’s fish, wildlife and human communities.”

WSC Alaska Program Director Emily Anderson