Experts are happy—but holding on to their confetti.

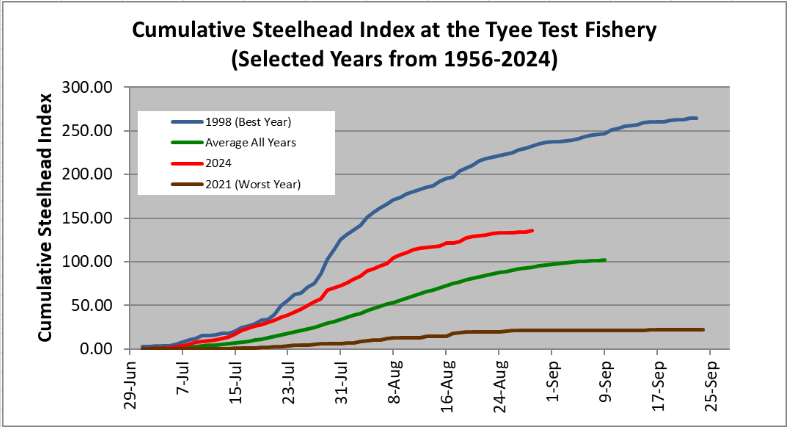

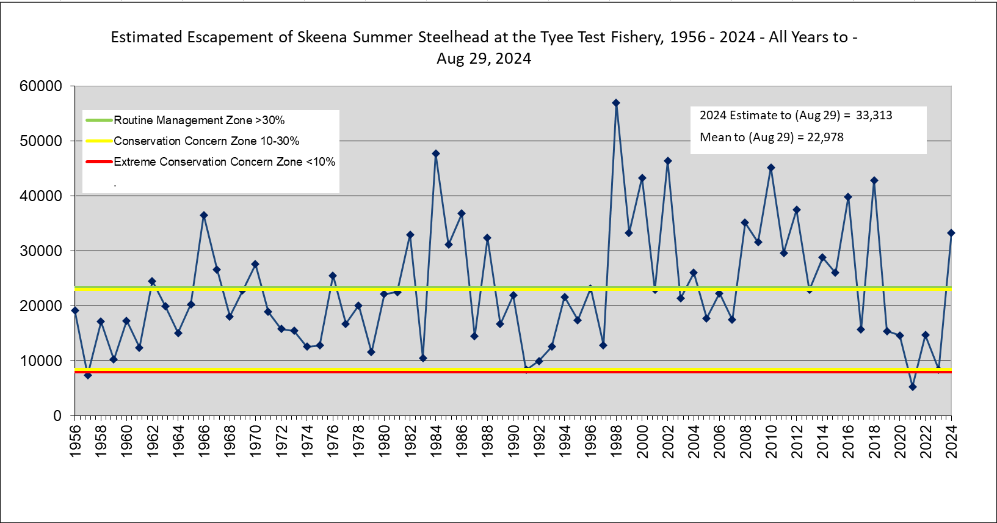

By late August, sighs of relief echoed across the Skeena Basin. Numbers were in from the Tyee Test Fishery: more than 33,000 steelhead had passed the lower Skeena—up from 2023’s run of 10,000 fish, and the 13th best return on record.

“We’re happy that returns are strong,” says Greg Knox, Executive Director of SkeenaWild, a core Wild Salmon Center partner. “But one year doesn’t make a trend.”

Knox’s note of caution holds water. After all, we’re just three years distant from the river’s lowest steelhead returns on record—when just 5,400 steelhead passed the test fishery. For at least the past five years, Knox says, the reality is that Skeena steelhead returns have remained stubbornly low.

“There can be a sense, with a strong year like this, that everything is fine again,” Knox says. “But we’re not. If we’re serious about the long-term health of these fish, we have to consider the bigger picture.”

“There can be a sense, with a strong year like this, that everything is fine again. But if we’re serious about the long-term health of these fish, we have to consider the bigger picture.”

SkeenaWild Executive Director Greg Knox

An Ocean of Unknowns

2024 hasn’t just been good for Skeena steelhead. Numbers are up elsewhere in North and Central British Columbia rivers like the Nass, and even down in the Columbia River Basin.

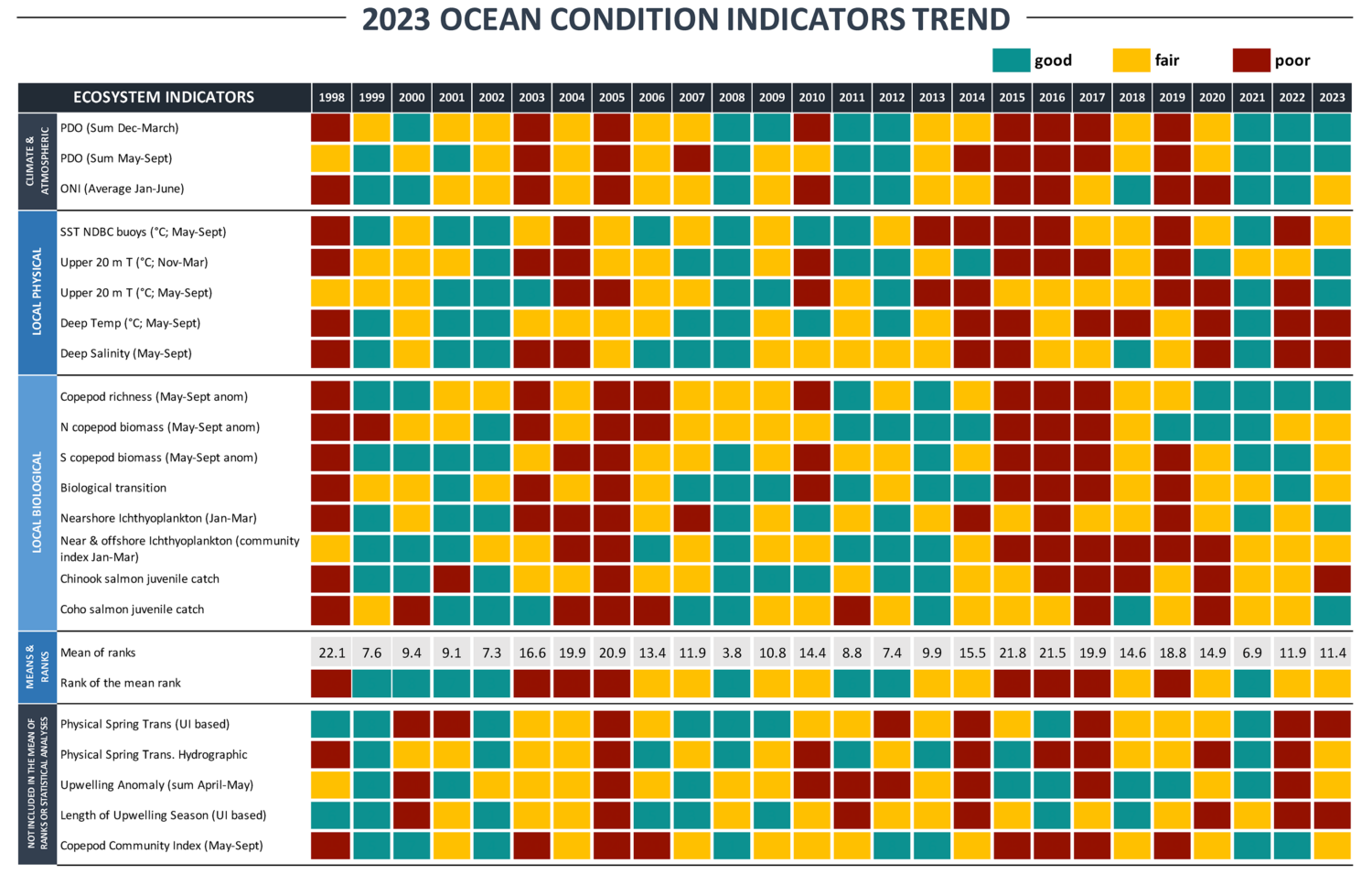

For scientists like Dr. Nate Mantua—a WSC Board Member, Science Advisor , and head of the Salmon Ecology Team at NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center in California—broad patterns like this indicate that something may be happening at sea.

Steelhead are intrepid ocean travelers, covering distances that can surpass 4,000 kilometers (roughly 2,500 miles) in their multi-year marine journey. Across a broad expanse of the North Pacific Ocean, different steelhead runs overlap, resulting in shared life experiences. The trajectories of steelhead can also overlap with other salmonids—pink salmon, most notably.

“Steelhead tend to stay in the top few meters near the surface, where they’re subject both to warming water and fierce resource competition from much more abundant species like pink salmon,” Dr. Mantua says. “Growing evidence suggests that these factors are helping to drive long-term declines in West Coast steelhead.”

“Evidence suggests that warming water and fierce resource competition from much more abundant species like pink salmon are helping to drive long-term declines in West Coast steelhead.”

Dr. Nate Mantua, NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center

But sometimes, if rarely these days, shifts in marine conditions can prove temporary boons to salmon and steelhead. Though in a system as vast as the ocean, Dr. Mantua is reluctant to guess where or how things might have gone right.

“When you see returns like this year’s, it’s an indicator that 2024 steelhead didn’t get knocked down by tough ocean or stream conditions—that a lot of things lined up in their favor,” Dr. Mantua says. “It shows that these populations still have a lot of potential, when ocean and stream conditions aren’t sharply limiting.”

“Returns like this year’s, it’s an indicator that 2024 steelhead didn’t get knocked down by tough ocean or stream conditions. It shows that these populations still have a lot of potential.”

Dr. Nate Mantua, NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center

If ocean conditions can arguably take the bulk of credit for boosting 2024 steelhead returns, Knox says that means fisheries managers should be careful about reading too much into their own last-minute pivots.

For him, one comparatively good year doesn’t change the need for humans to keep reducing pressure on steelhead. He notes that over the past six decades, the Skeena’s annual summer runs have rarely left the escapement “concern zone”—when it’s estimated that too few fish are making it to spawning grounds to sustain future runs.

“Ocean conditions in the North Pacific are widely variable,” Knox says. “Next year, we could easily be right back in a place where ocean conditions shift, and we’re again having to consider closing fisheries.”

Knox says that while we can’t control the ocean, we still can make a difference for steelhead, both near shore and in freshwater. For the past few years, SkeenaWild and other organizations have been pushing for reforms to Southeast Alaska’s marine salmon fishery, where Skeena steelhead can be caught alongside target pink salmon and other species. A solution, Knox says, is to move the fishery closer to shore. It’s an idea that’s taking root across the Pacific, as a growing body of science points to the promise of selective, terminal fisheries in building more sustainable fisheries.

“We strongly support the expansion of Indigenous selective fishing practices in the Skeena,” Knox says. “This is the future of fishing.”

He points to the Kitselas First Nation’s new fish wheel, as well as dip-netting at the Gitanyow Fish Camp at Lax An Zok—where Knox and partners at Watershed Watch Salmon Society recently saw firsthand the efficiency of these selective practices in action.

If one good year doesn’t make a trend, perhaps sustained action can get us there: doing everything we can, every year, to get more Skeena steelhead upriver.

When that happens, Knox says, he just might be ready to break out the confetti.