The Wild Salmon Center Science Advisor wants to change the way we think about “winning” salmon rivers.

In a warming world, the race is on to predict the future’s best salmon rivers. Dr. Jonathan Armstrong, for one, is holding onto his chips.

“When we talk about ‘climate smart planning,’ we often end up trying to pick winners and losers,” says Dr. Armstrong, a Wild Salmon Center Science Advisor and professor of ecology at Oregon State University. “But that’s a pretty harsh zero-sum game.”

And it might not play out well for salmon. A narrow conservation focus on “winners” could mean that we overlook many larger streams and rivers that play important roles in supporting migratory trout and salmon.

“We can’t save it all,” Dr. Armstrong says. “But we also don’t want a future where we’ve only managed to protect a handful of cold mountain streams and the small trout that can live out their life-cycle without migrating.”

Salmonids need cold water, he notes. But they’re also hardy travelers with life histories that vary widely. This life history diversity is key to the overall climate resiliency of these species, like different stocks in a diversified investment portfolio.

“We can’t save it all. But we also don’t want a future where we’ve only managed to protect a handful of cold mountain streams.”

Dr. Jonathan Armstrong, WSC Science Advisor

To maximize fishing opportunities in a warmer world, Dr. Armstrong says we can’t lose sight of places some might call the “losers”—places like the Klamath Basin on the Oregon/California border, a centerpiece of his research for the past nine years.

“Klamath Lake can get to almost 80 degrees in the summer,” Dr. Armstrong says. “And yet it still provides the vast majority of annual growth for migratory redband trout and the fisheries that target them. This doesn’t look like trout habitat, but it is.”

Oftentimes, he says, rivers that some dismiss as too hot, like the Klamath, are only hot for a few weeks of the year. Most of the year, Klamath Lake is a rich growth environment for resident trout. When the lake does get too hot, trout here have the option to duck into cold, spring-fed upper tributaries: the kind of habitat connectivity that’s critical to life history diversity.

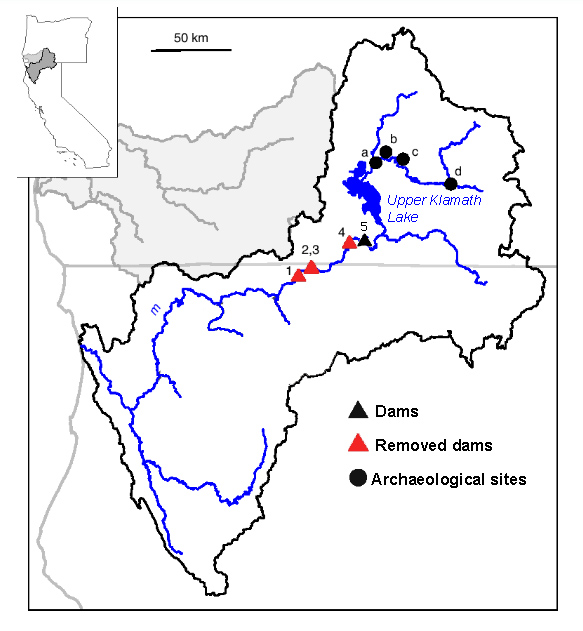

Now, the Klamath’s habitat connectivity is expanding—and it could be a game-changer for wild fish. In fall 2024, the largest dam removal project in history was completed on the Klamath mainstem, enabling Chinook salmon and other species to reclaim miles of historic habitat for the first time in a century.

As salmon find their way higher in this system—including Klamath Lake and its upper tributaries in Oregon—Dr. Armstrong is among those wondering how they’ll navigate decades-worth of change wrought by agriculture, development, and big climate shifts.

Like the resident trout who’ve long thrived behind the dams, Dr. Armstrong has hope that salmon will find ways to adapt to the upper Klamath. He has to have hope. Right now, the Klamath Basin seems anomalous: a place of climate extremes that also supports salmonids. But in the future, challenging conditions could be the norm across the Pacific Northwest.

“Klamath Lake can get to almost 80 degrees in the summer. This doesn’t look like trout habitat, but it is.”

Dr. Jonathan Armstrong, WSC Science Advisor

“Being climate smart is not as simple as identifying places that have worse climate stressors and writing them off,” Dr. Armstrong says. “And that’s actually really good news. It means these areas can still contribute.”

Below, he shares more about the importance of big rivers, why salmon refuges aren’t “refugia,” and how we can put out the welcome mat for future Klamath Lake salmon.

“Being climate smart is not as simple as identifying places that have worse climate stressors and writing them off. And that’s actually really good news. It means these areas can still contribute.”

Dr. Jonathan Armstrong, WSC Science Advisor

A Conversation with Dr. Jonathan Armstrong

Wild Salmon Center: What’s your connection to the Klamath?

Dr. Jonathan Armstrong: I grew up in Ashland, Oregon, and I was into fishing. I would come over to Klamath Lake when I was a teenager and fish there. And I was kind of just fascinated by these giant migratory trout, and the diversity of habitats in the upper Klamath Basin. Here you have a lake that turns neon green in the summer because it’s so eutrophic. But you also have snowmelt-fed mountain tributaries, springs, and a hundred-kilometer river like the Sprague.

How did you go from fishing the Klamath to fishing for answers about salmon in the Klamath?

In graduate school, a lot of my work was about how fish and wildlife exploit habitat diversity. Specifically, I was looking at how coho salmon move to patches of warm water, because at the northern extent of the range, where I was, in Bristol Bay, they’re limited by cold water.

Then when I got a job at Oregon State University and thought about local projects in the Pacific Northwest, and my proximity to the Klamath system. This just seemed like the perfect place to flip the question. Because here, at the southern portion of salmon range, the physiological constraint is oftentimes that it’s too hot instead of too cold.

So the question was what are the outer bounds of temperature? How hot is too hot for salmon, and how cold is too cold?

I started doing work on how trout exploit patches of cold habitat to get through summer. The Klamath redband trout move to these beautiful spring-fed wetlands and rivers. They are the places I fished for them when I was younger. We found the fish can do impressive migrations to quickly find the summer refuges. But we also found they weren’t actually growing in these cool tributaries of the lake. This was surprising because they are big chunks of habitat; the fish don’t appear crowded like they do in some thermal refuge examples.

They were growing in the lake in spring and fall (when temperatures are optimal for trout). Virtually every trout we sampled in the lake had a full stomach. It reminded me of rainbow trout in Alaska when sockeye are spawning, but these fish were eating chubs, sculpin, and leeches. This led me to become more interested in how warm habitats contribute to cold-water fisheries. How much we might be missing if we only focus on the places that stay cold year-round?

Are you saying that focusing on cold water is overrated in salmon conservation?

Cold water is critical—whether it’s a smaller spring-fed habitat that helps migratory fish get through a stressful period or a larger portion of a watershed that is forecasted to stay cool under climate change.

I think most folks recognize that salmon and trout need warmer downstream habitats to complement these cold habitats, but they assume that in a warmer future, cold water will be limiting and we can ignore the rest. I worry about this mindset, because warm habitats that are intact and functioning may be rare, based on how humans develop watersheds from the bottom up.

Our research group is finding that it’s usually a small subset of warm habitats that salmonids take advantage of. For example, the giant redband trout in Klamath Lake use undeveloped shorelines, while juvenile redband trout in the Sprague River use steep canyons.

So what do fish do when it gets too hot in the Klamath?

In the Upper Klamath Basin and in other areas, we see multiple strategies. The large redband trout that use the lake, they all go to cool refuges in summer. But just downstream, between the Keno Dam and what was J.C. Boyle Dam, trout stay in the mainstem river during summer and tolerate warm temperatures in oxygenated canyon waters. We see similar contrasts with coastal cutthroat trout in the Willamette River. It’s a neat example of life history diversity and how these populations can exploit surprisingly warm water if there is oxygen and food.

So what can we do to maximize the chances that rivers like the Klamath, down in the southern range of salmon, stand the best chance of continuing to support wild fish?

We may not be able to make downstream habitats suitably cool during the peak of summer, especially in the face of climate change. But what we can influence is the duration of the year that places are suitable, and how well they support fish during those periods.

For example, Upper Klamath Lake will probably never be a great place for salmonids in July. And perhaps it never was, since it’s naturally warm and eutrophic. But groups including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Trout Unlimited, the Klamath Tribes, and many others are doing process-based restoration to reconnect floodplains and capture nutrient-rich sediments that turbocharge algae blooms. This could prolong the portion of the year that the lake is suitable for salmonids, by influencing dissolved oxygen and pH. This could make a wider target for the timing of migration that allows fish to survive, or it could give fish more time to grow rapidly in the lake during spring.