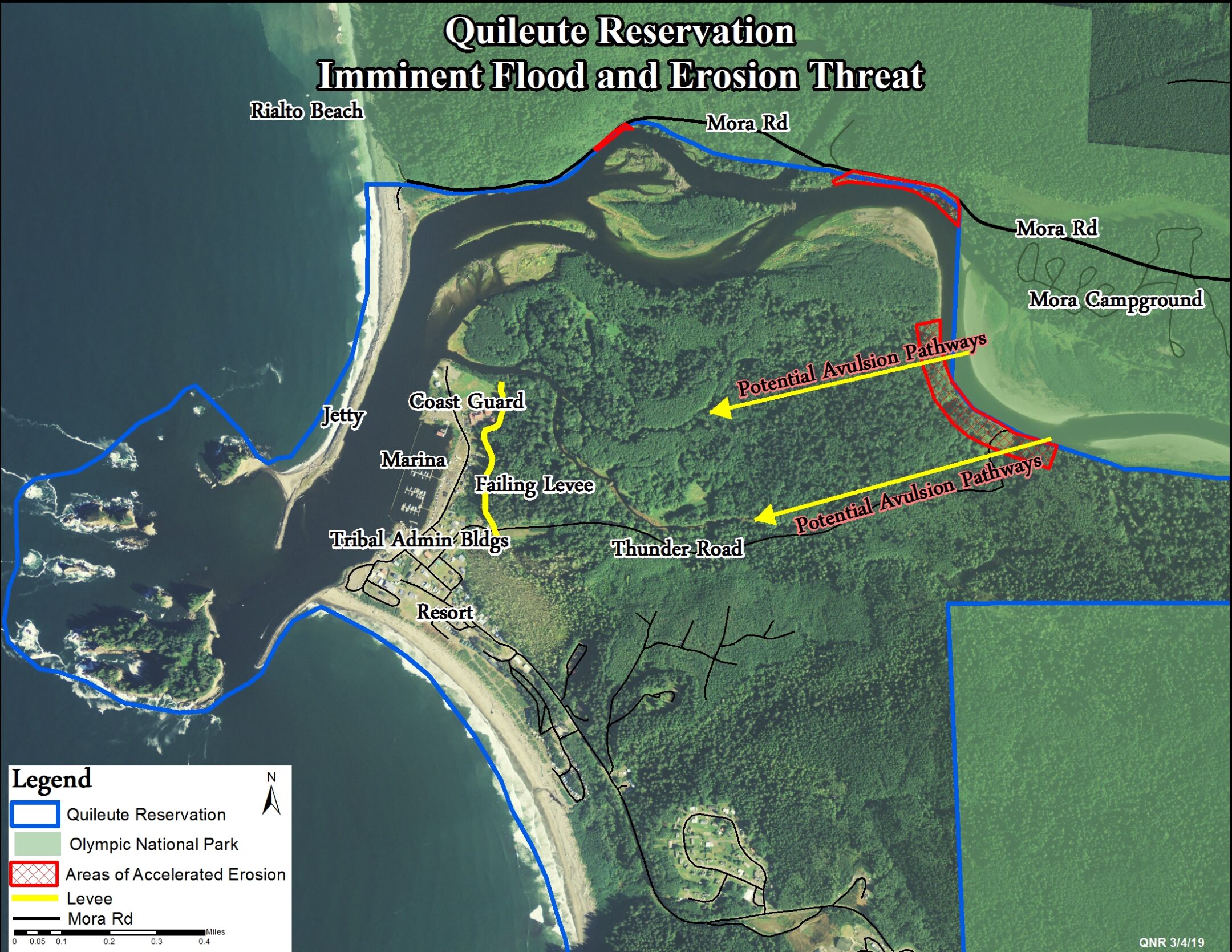

Gouged by flooding and human interference, the Quillayute River could soon change course—and flood the Quileute village of La Push. Slowing its path is a win-win for both people and fish.

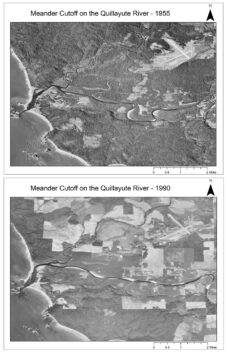

At first, floodwater bit just a few feet into the river’s steep-cut bank. Then it ate another few feet. Then more. On the western edge of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, the salmon-rich Quillayute River is shifting: creeping ever closer to an old backwater channel that, like a railroad switch, offers this fast-flowing salmon river an alternate path to sea.

“The river is trying to straighten,” explains Nicole Rasmussen, a water quality biologist for the Quileute Tribe, whose two-square mile reservation sits just south of the current river mouth. A while back, the Quillayute cut itself off from a historic oxbow upriver. In more recent years, hardscape interventions—such as large rocks sealing the river’s north bank placed there for emergency erosion control—have made things worse.

Now, with flooding on the rise along the Olympic Coast, it’s estimated that high water will wipe out the bank’s remaining 140 feet buffer within the next few years—shunting the diverted river right through the lower Quileute village of La Push.

No one hears that clock ticking more than the Quileute’s roughly 800 tribal members. For years, they’ve fought to make others understand the problem. State and federal agencies recently released funding for the Quileute to complete a river restoration plan within six months, one based on green infrastructure approaches like introducing flow-slowing logjams into the river.

At stake is survival: both for this village and the river’s salmon runs, prized by the Quileute, regional anglers, and Southern Resident orcas off the Washington coast.

Next, the Quileute must put that plan into action—before it’s too late. At stake is survival: both for this village and the river’s salmon runs, prized by the Quileute, regional anglers, and Southern Resident orcas off the Washington coast.

“In 2003, the Coast Guard station flooded completely,” says Rasmussen, previewing potentially worse floods to come. “My office is next to that, and next to that is the Tribal Office, and the restaurant, and the rest stop, and the school. So it would take out a lot of the lower reservation.”

The Quileute’s tiny reservation, Rasmussen explains, doesn’t give them many places to go. In 2012, federal tsunami legislation set aside a bit of land to the south for the nation to begin moving uphill—work that starts this winter with the school. But the Quileute still hope to restore this river, and continue fishing for the salmon core to their culture and subsistence. Even as they clear land for their new, higher-elevation school, they’re stockpiling felled trees for the plan’s strategic logjams. Now, a strengthening coalition, including the Wild Salmon Center, is stepping up to help speed things up.

“This will be the largest scale restoration effort the Quileute have ever undertaken, and we’re rallying important partners including the Army Corps of Engineers, National Park Service, and leaders including Congressman Kilmer,” says Wild Salmon Center Washington Program Director Jess Helsley.

Big agencies like FEMA, Helsley says, are finally seeing the value of green infrastructure, particularly as traditional hardscape flood reduction techniques (such as levees, sea walls, and dams) have proven inadequate to the challenges of climate change. The values of green infrastructure extend beyond flood-proofing human communities; they also provide widespread ecosystem benefits, such as improved habitat for keystone species like salmon.

“Engineered logjams help trap sediment, creating those cold water pools that fish love,” explains Helsley. “The fish can duck in, breathe, move in and out around that wood. Logjams also help reconnect the river with floodplains, which slows the river down and recharges groundwater in the process.”

Those cold floodplain pools are also vital to the spawning and rearing of the river’s coho, steelhead, and Chinook populations. Today, the Quillayute represents one of the last salmon strongholds in Washington State.

“The Quillayute doesn’t have any threatened or endangered runs of fish, and we’d like to keep it that way,” says Rasmussen. “We have momentum now, and people are excited.”

Now, Rasmussen says, the coalition needs to get this plan rolling—and that means finding new resources, fast. Because for the Quileute, and the salmon they cherish, there’s literally no going back once this river jumps. It’s a threat that grows closer with every winter storm.

The coalition needs to get this plan rolling—and that means finding new resources, fast. Because for the Quileute, and the salmon they cherish, there’s literally no going back.