Can logging coexist with Canada’s largest sockeye salmon system? SkeenaWild’s Greg Knox says yes—and shares how.

Deep in the temperate rainforests of northwest British Columbia, grizzlies are feasting on wild salmon. Here, too, are eagles and minks, wolves and wolverines, otters and endangered amphibians.

The river where they all make camp is the Babine, a pristine tributary of the Skeena. The Babine is a famous fishing river for humans, too: home to world-class steelhead lodges, and commercial and subsistence fisheries for the Gitxsan and Lake Babine Nations.

But the Babine and its abundant salmon runs are at risk, warns Greg Knox, Executive Director of SkeenaWild, Wild Salmon Center’s local partner. The logging trucks are circling, pressing in from the east as large timber companies flee interior wildfires and pests, hungry for Canada’s last, great old growth stands.

“Forestry in British Columbia has been in crisis for a long time,” says Greg Knox. “And it’s getting worse. This is our opportunity, right now, to fix the unsustainable way the logging industry does business.”

Knox says reform is necessary to preserve the Skeena as a stronghold for salmon, and the way of life of the communities that depend on them.

The threat is coming to a head after years in which the region’s logging companies have operated without adequate federal and provincial oversight. Freed from earlier provisions that encouraged timber to be processed locally, these companies now truck mass raw product out of town. Permitted to self-regulate, they log right down to the stream’s edge. And with the price of Canadian lumber dropping abroad, overharvesting is how these companies now aim to meet their bottom lines. These practices are dangerous, Knox says—for the Skeena watershed, salmon, local industries, and First Nations.

“People see it happening,” says Knox. “They’ve seen the mills shut down, raw logs driven by and being put in shipping containers to China. Those are jobs going out of province. We’re not anti-logging. We just know it can be done smarter and more respectfully.”

For Knox, the fixes are obvious and commonsense. They’re detailed in a January 2020 SkeenaWild forestry study. The province can start, he says, by boosting its support for Indigenous-led land use planning. That means, in part, shifting forest license allocations toward First Nations instead of large corporate interests without local ties.

“We’ve seen that First Nations and local communities are better forest stewards,” Knox says. “And they often manage them for other benefits, like foraging, wildlife, fish, and recreation.”

“We’ve seen that First Nations and local communities are better forest stewards. And they often manage them for other benefits, like foraging, wildlife, fish, and recreation.”

Greg Knox, SkeenaWild Executive Director

Other SkeenaWild solutions include aligning forestry with Canada’s Wild Salmon Policy, restoring provisions that require more timber products to be processed locally, and reducing B.C.’s “annual allowable cut” to prevent overharvest.

The province could also encourage more logging operations to seek environmental certification from third parties such as Canada’s Sustainable Forest Management System and the international Forest Stewardship Council. Certification has the added advantage of opening up lucrative new markets, as some major retailers like Home Depot only buy certified lumber. (And they do so, Knox says, at a higher price point.)

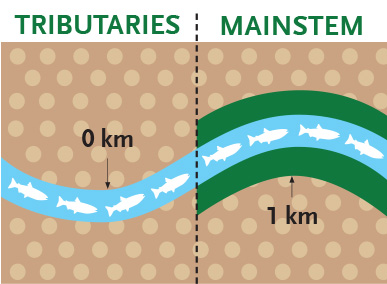

Now, SkeenaWild—along with indigenous partners and the Babine River Foundation—says the onus is on the provincial government to embrace these sustainable forestry practices before it’s too late. One potential turning point is a proposed new $1 million logging bridge; if built, the bridge would open up untouched Babine tributaries like the Shelagyote and Shedin to logging for the first time.

That could have ripple effects across the watershed, starting with water quality and fish habitat, says Carrie Collingwood, co-owner of Babine Norlakes Steelhead Camp and the director of the Babine River Foundation.

“We have clients who’ve fished with us for 30 years,” says Collingwood. “They say the river is more volatile, with increased blowouts during the rainy season. We all attribute it to logging—river crossings, runoff, sedimentation. It ruins the fishing experience.”

It’s not just this year’s fishing experience that she’s worried about. Sedimentation drives down productivity on salmon and steelhead spawning grounds that will bring future fish back here. Increased logging also threatens First Nations cultural heritage sites that cluster near the river. And it encroaches on the Babine’s grizzlies—one of the highest such concentrations in North America.

“There are lots of reasons to protect these watersheds,” Knox says. “Logging can co-exist with the largest sockeye salmon system in Canada. We already have the tools. Now we need to use them.”

Logging can co-exist with the largest sockeye salmon system in Canada. We already have the tools. Now we need to use them.”

Greg Knox, SkeenaWild Executive Director