Wild Salmon Center’s investments in salmon watersheds bring work to rural communities. For fishing towns on the Oregon Coast, it’s smart money now, and for the future.

About 15 miles east of the central Oregon coast, travelers on the Florence-Eugene Highway hit the tiny hamlet of Mapleton right at their first hop over the Siuslaw River.

“Blink and you’ll miss it,” laughs Mizu Burruss, project manager for the Mapleton-based Siuslaw Watershed Council. “I think we might be the second largest employer in town, outside of the school district.”

Jobs have long been scarce on the Oregon coast, even with the last decade’s recovery. Contributing factors include the continued contraction of the timber and fishing industries, along with the volatility of seasonal tourism. The coast’s heightened economic vulnerability means any broader dip hits the coast especially hard. Now, with the global spike in pandemic-related unemployment, the Oregon coast is reeling; as of early May, four of the six Oregon counties with the highest rates of unemployment claims were coastal.

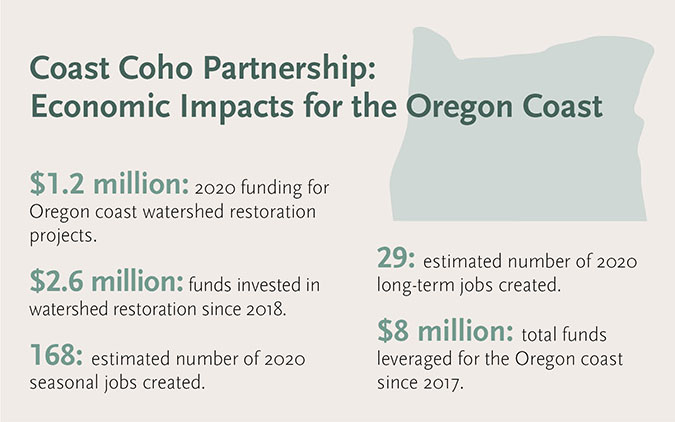

Which is why Burruss is so proud of the state, federal, and philanthropic dollars the watershed council and its partners are bringing to the area—including more than $525,000, since 2018, in direct grants from the Wild Salmon Center via the Coast Coho Partnership. The CCP is a young, Wild Salmon Center-managed alliance of public and private partners working to recover endangered Oregon coast coho through strategic action plans and targeted on-the-ground restoration projects. Since 2017, CCP has leveraged nearly $8 million in direct and matching funding for projects up and down the Oregon coast.

Burruss is also proud that the bulk of these dollars stay here, in the community. She helps manage what are often multi-year projects in the 773-square-mile Siuslaw watershed, meaning regular seasonal employment for dozens of local log fellers, tree tippers, heavy equipment operators, excavators, and truck drivers. The council’s permanent staff of seven employees also work here, in Mapleton, providing good jobs in an area that really needs them.

“I often struggle to convey to people just how much one job here means,” says Burruss. “For me, it means my family of five can live here, and I can put that money right back into the local economy. For others, it’s another source of income when the logging season is slow.”

BY THE NUMBERS

Jobs and income are go-to metrics to assess the economic impact of watershed restoration work within a community. For example, last summer Buruss hired timber fellers, choker setters, and an entire helicopter crew, among other workers, for phased restoration work adding wood on the Siuslaw’s Upper Indian Creek—work that continues this summer, with additional hires.

But the economic benefits of this work ripple out. Look to the specialized helicopter crews that Buruss will bring in later this summer: pilots and mechanics and stream crews, up to 12 people, all of whom will book lodging in Florence for stays often extended by weather, logistics, even wildfires. When not working, these crews eat at local restaurants and breweries, pump money into local shops, and rent dune buggies on the weekend. Then there are the local nurseries that provide native plants for stream revegetation, and quarries that supply building materials. Local tax bases grow as loggers supplement incomes with off-season restoration work, boosting funds for local services and schools.

“Numbers mean different things in different places,” says Burruss. “In the city, these numbers might look small. But out here, in terms of employment, they’re huge.”

One study from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows that every $1 million the agency invests in watershed restoration work creates 15-30 jobs. A University or Oregon report found that 80 percent of every dollar invested in an Oregon restoration project stays in-county, and 90 percent stays in-state. These economic impacts are major co-benefits for the Coast Coho Partnership and three of the funding partners which co-founded it: the NOAA Restoration Center, Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board, and National Fish and Wildlife Foundation.

“Watershed restoration work requires local partners who can walk the streams and build working relationships among neighbors,” says Mark Trenholm, Wild Salmon Center’s Coastal Program Director. “To sustain this work and do it right, you invest in the people working on the ground. That’s exactly what we’re here for.”

A NOAA study shows that every $1 million the agency invests in watershed restoration work creates 15-30 jobs.

Case in point: Burruss’s team, deep in logistics for its summer 2020 field projects, isn’t the only CCP partner hiring this summer in the Siuslaw watershed. The Siuslaw Soil and Water Conservation District is also booking truck drivers, dozer operators, and excavators for another CCP-funded project at the confluence of the North Fork Siuslaw and McLeod Creek. All told, field projects restoring key coho streams in the Siuslaw will create 63 seasonal jobs in summer 2020, and support six permanent positions.

Multiply that by CCP ‘s active, ongoing work up and down the Oregon coast. This year alone, CCP will fund 16 field projects in six Oregon watersheds—from the Nehalem River to the Rogue: an influx of some $1.2 million in investment that directly translates to 168 short-term and 29 long-term workers.

“Numbers mean different things in different places,” says Burruss. “In the city, these numbers might look small. But out here, in terms of employment, they’re huge.”

RESTORATION ECONOMY

For some of Burruss’s neighbors in Mapleton, it’s a bit ironic that the watershed council pays good money to put logs back into streams “cleaned” of woody debris over the last century.

Placing logs into streams—sometimes with massive root wads still intact—is one way that restoration projects improve habitat for coho and other salmon. Strategic log jams slow and redirect water to create pools, side channels, cold water pockets, and other safe places for rearing fish to feed and rest. Historically, these streams were full of downed trees, beaver dams, and shallow side channels, all of which benefited fish. But over time, much of that complexity was lost, as logs were removed, in part, to create unobstructed waterways for timber transport.

Burruss understands the irony of adding logs back in. But she sees this work as an important, adaptive chapter in Oregon’s rich timber history. The projects she manages require workers skilled in the felling, tipping, and moving of massive trees. Depending on the size and scope of the project, she’ll need anywhere from two to five skilled fellers and tippers. And the insights these experts bring to restoration projects is critical.

“We often have contractors who like these jobs because it’s a different type of thinking,” says Burruss. “Sometimes the contractors we hire modify the designs because they see a good way to improve them, based on their experience. More often than not, our design concepts are improved on the ground by the contractors. And that brings them real satisfaction.”

For the next several years and beyond, project managers like Burruss will have jobs to offer them. But for Wild Salmon Center’s Mark Trenholm, restoration work holds an even greater economic promise for Oregon’s coastal communities—the promise of recovering threatened coho salmon enough so people can fish again.

The ultimate payoff lies in the future: restoring the lifeblood of coastal communities, and helping them fish again.

Logging isn’t the only heritage industry that’s challenged on the Oregon coast. For many residents, salmon fishing is a core part of their identity, a tradition that stretches back millennia. But for decades, fishing for coho has rarely been an option for indigenous, commercial, and sport fishers. This has meant millions of dollars lost in guiding fees, food sales, and gear revenue, and a traditional way of life threatened for local tribes.

If coho restoration work is bringing new jobs to the coast now, says Trenholm, the ultimate payoff lies in the future: restoring the lifeblood of coastal communities, and helping them fish again.

“Oregon Coast coho is well-positioned for a comeback,” says Trenholm. “Local communities get it: they want to fish for coho again, and know that we can get there through strategic restoration and better stewardship of working lands.”