If the Dams Fall

On Northern California’s Klamath River, dams have brought spring Chinook to the brink. To save the species, Indigenous knowledge is key.

Part II, in the First Salmon, Last Chance story series.

By Ramona DeNies

As a child, Charley Reed and his five brothers watched their father fish near their home on the Klamath River. Ron Reed, Sr., a Karuk ceremonial leader and cultural ecologist, balanced on slick rocks, working a traditional dip net—10-foot twin poles strung with a handmade net—through the pool below Ishi Pishi Falls, the Karuk people’s community fishery, a place they consider to be the center of the world.

If the senior Reed caught a Chinook, he pulled the net toward one of his older boys, who clubbed the salmon, fast. The younger ones, next, sacked the fish and set it aside; later, they were responsible for carrying out the day’s catch across the backwaters for cleaning and sharing with elders and families. This process wove fishing with childhood rites of passage, family life, and community values like reciprocity and hard work.

For the Karuk, Yurok, and Hoopa people of Northern California’s Klamath and Trinity rivers, salmon fishing traditions have been passed down for countless generations. Each year, this starts with the arrival of spring-run Chinook, the first salmon, prized above all.

“Traditionally, we wait for the return of the first spring Chinook salmon to begin the First Salmon Ceremony, the first World Renewal ceremony,” says Reed, 25, now a graduate student at Humboldt State (and new father himself). “But the decline in spring Chinook returns makes this tradition hard to keep alive.”

Reed, a Hoopa Valley Tribal member, Karuk cultural practitioner, and descendent of the Yurok people, says life lived alongside spring Chinook is a nonnegotiable part of being a river person. But for more than 150 years, key decisions impacting Klamath salmon runs—from destructive western mining and land use practices to the construction of massive dams—have been made by far-away state, federal, and private interests, largely without input from the Tribes. For the Karuk, these impacts stem from the federal government’s failure to ratify its own treaty with the Tribe in the early 1850s, precipitating a systemic denial of access to hunt, gather, and fish, and to manage their own watersheds, firesheds, and foodsheds.

Now, with the Klamath’s spring Chinook runs in a tailspin, the Karuk are part of a national campaign fighting to remove four upper Klamath dams—dams that, for a full century, have blocked springers from hundreds of miles of critical habitat. But that dam removal process, codified in a 2016 agreement and supported by government entities including the states of Oregon and California, has stalled out in a series of procedural curveballs and delays.

“This is the last chance for a species that’s about to go extinct,” says Reed. “Dam removal is one hopeful thing, and it’s at a standstill. Yet another faulty promise. It’s triggering, and it’s unacceptable. Tribal communities need to consistently be in this process. Protection needs to be secured for all time.”

This is the last chance for a species about to go extinct. Tribal communities need to consistently be in this process. Protection needs to be secured for all time.”

Once, Reed says, hundreds of thousands of spring Chinook returned to the Klamath every year. This summer, surveys on the Salmon River, the Klamath’s last remaining spring Chinook stronghold, counted just 106 springers. (See First Salmon, Last Chance – Part 1.) For the Karuk, this staggering decline has left the community reeling, in a state of profound mourning.

“We need the people who make decisions to understand how this affects us not just scientifically but ecologically and culturally,” says Reed. “The fish are the leading influence on the natural world for us, and they’re not in the picture. The world is out of balance.”

From the lack of salmon in Reed’s community, a range of problems cascade: food instability and familial disruption, loss of livelihoods and social cohesion. Young Karuk men are particularly at risk: of mental health issues, substance abuse, incarceration. The impacts ripple, reaching the entire community.

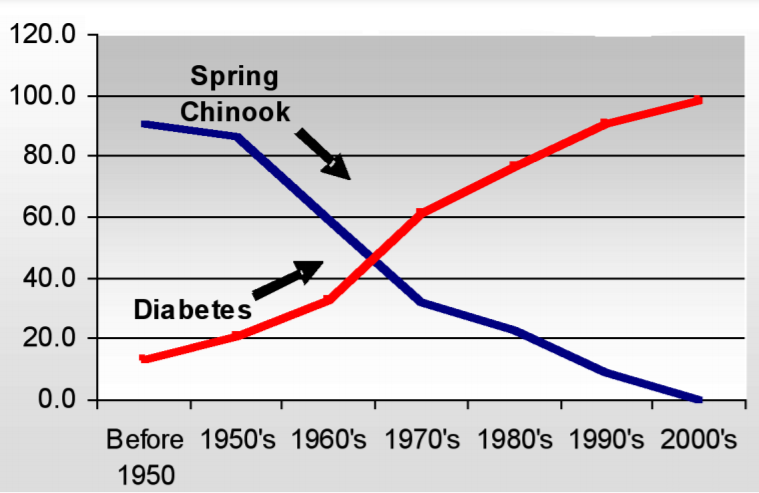

Reed points to the work of a mentor, Dr. Kari Norgaard, a professor of sociology at the University of Oregon and frequent research collaborator with Ron Reed, Sr. In one project, Dr. Norgaard graphed Karuk diabetes rates rising since the 1950s, with a second line plummeting in mirror opposition: the Klamath’s annual spring Chinook counts. Karuk Tribal members consumed 1.2 pounds of salmon per person per day before Western contact; by 2019, they ate less than five pounds of salmon per year.

Indigenous communities know how to recover these populations, Reed says; ask a Karuk elder, and they’ll tell you. For millennia, salmon-centric Indigenous communities across the North Pacific have successfully managed sustainable runs through fish weirs, controlled burns and smoke, upslope maintenance, careful observation, and ceremonies that enabled salmon runs to reach spawning grounds before harvest.

Now, more than ever, Indigenous knowledge must inform state and federal salmon management practices, Reed says, if the Klamath’s springers are to survive, along with a river people’s foundational way of life.

“My biggest fear is that we as Karuk people, fish-loving people, that we’ll lose the privilege to continue protecting and honoring our more-than-human relatives,” says Reed. “I don’t know if scientists recognize that if spring Chinook don’t come back, that is a form of cultural genocide.”

I don’t know if scientists recognize that if spring Chinook don’t come back, that is a form of cultural genocide.”

Two hundred fifty miles east of the North California coast, the sunbaked remnant of a giant Pleistocene lake pools just above the Oregon-California border.

Klamath Lake, from which the Klamath River flows, stretches 25 miles over the basin floor, a marshy paradise for migratory birds and rainbow trout. That’s despite eutrophic summer conditions that can promote algal blooms and kill fish who linger here, rather than move into the lake’s cold, spring-fed upper tributaries.

“Klamath Lake in summer is just a terrible place to be as a cold water fish,” says Wild Salmon Center Science Director Dr. Matt Sloat. “But in other seasons, it’s incredibly productive. Trout can grow ten pounds in a few years by gorging in the lake in spring and fall, then holding in the tributaries during summer. It could be game-changing for spring Chinook, if they could get there.”

Right now, they can’t. Springers headed for paradise instead meet the eighty-year-old Iron Gate Dam some 25 miles northeast of Yreka. The 170-foot-high earthen wall is just the first of four hydroelectric dams run by PacifiCorp blockading the next 60-some river miles: Copco 1, Copco 2, and J.C. Boyle Dam a few miles south of Klamath Lake.

For twenty years, the Karuk, Yurok, and Klamath Tribes—along with a host of scientists, sport fishers, and conservation groups—have led the fight to remove these century-old salmon barriers, with support from Oregon and California. In 2016, the coalition came to an agreement with PacifiCorp and its parent company, Berkshire Hathaway. The advocates have economics in their favor: the aging structures produce little hydropower, no irrigation water, and offer no flood control. Meanwhile, federal relicensing will require fish passage improvements projected to cost far more dam removal.

Under that agreement, the nonprofit Klamath River Renewal Corporation was created to obtain needed permits and assume sole responsibility for the project. A schedule was set for dam removal. Then, in July 2020, the Federal Regulatory Energy Commission threw a wrench in the plans, ruling that PacifiCorp, contrary to its wishes, must remain a liable co-licensee alongside the nonprofit. As PacifiCorp and Berkshire Hathaway Energy went quiet, dam removal advocates were again left without a timeline.

The dams’ longevity, too, has muddied the salmon restoration argument for their removal. Since the 1910s, no ocean-returning fish on the Klamath River could climb higher than Copco 1. Maybe, asked some opponents, salmon never reached Klamath Lake in the first place?

Indigenous knowledge was mostly ignored. And old newspapers, settler accounts, ethnographic accounts indicating that salmon migrated above the dams, the skeptics just dismissed. Then archeologists found the middens.”

“Dam removal skeptics found it easy to create confusion later, because the dams went in before western scientists had “hard data” on salmon numbers,” says Dr. Sloat. “Indigenous knowledge was mostly ignored. And old newspapers, settler accounts, ethnographic accounts, other sources indicating that salmon migrated above the dams, the skeptics dismissed as just anecdotes. Then archeologists found the middens.”

Middens, or ancient mounds of human detritus—everything from old tools and artifacts to shells and bones—are common throughout the Klamath Basin. Various archeological sites on Upper Klamath Lake tributaries had found salmonid bones. But were these bones from rainbow trout, still present today above the dams, or ocean-going salmon like spring Chinook?

To solve this mystery, Dr. Sloat and a team led by Dr. Tasha Thompson of Michigan State University set out to take a fresh look. Supporting their 2017 research was a genetic breakthrough from Dr. Thompson’s partner Dr. Mike Miller, of UC-Davis, who had recently discovered the precise gene that distinguished spring-run and fall-run Chinook. (See Part III – The Key in the Code.)

The lab results proved it: Chinook were here. At sites dating back some 5,000 years—and as recently as the 1860s—DNA identified both fall and spring Chinook bones in the middens above Klamath Lake.

“It confirmed that springers were present, and had been for centuries before the construction of the dams,” says Dr. Sloat. “This was amazing news. And it provides extra drive for salmon conservationists and Tribes like the Karuk to reconnect springers with the Klamath headwaters, one of the most climate-resilient freshwater habitats you could think of.”

But for Tribes and salmon managers to have a shot at reintroducing springers to the upper Klamath, the dams must come down before this salmon run blinks out. The crisis on the Klamath, says Dr. Sloat, has analogues across the Northwest: spring Chinook runs on the brink, as powerful entities drag their feet.

The crisis on the Klamath has analogues across the Northwest: spring Chinook runs on the brink, as powerful entities drag their feet.

“There’s this question: what exactly is a species?” For Craig Tucker, a policy advocate and former molecular biologist based in Arcata, California, spring Chinook are clearly an animal apart from their fall-run cousins; something that’s always been obvious to the Karuk Tribe, Tucker’s employer.

“The Karuk can draw on historical knowledge: they know spring Chinook look different, taste different, and show up at different times,” says Tucker. “Problem is, we’ve done a lot of really dumb things.”

One of those dumb things, he says, is the decision by government agencies like NOAA to lump spring Chinook with fall-run Chinook in management decisions—a policy that for decades has overlooked both springers’ distinct habitat needs and devastating decline.

“The idea was that if you lost all the springers but did some restoration work, you’d get springers again from the fall population,” says Tucker. “We now know that this isn’t the case, from Dr. Miller’s genetic work.”

Armed with this new insight—that once you lose a spring Chinook run, it’s gone for good—the Karuk Tribe and the Salmon River Restoration Council are petitioning NOAA Fisheries to protect Klamath springers under the Endangered Species Act. Endangered status, and the resources and restrictions that unleashes, could be a powerful tool in overcoming dam removal inertia.

“It costs more to get a new license to continue operating these dams than to remove them,” says Tucker. “But these are insurance agents, at the end of the day, and they’re worried about precedent. We’re talking about the biggest dam removal in the history of the world.”

The stakes are high, on both sides. As a mighty precedent, dam removal could energize countless other dam removal campaigns across the Pacific. For Tucker, dams are the single largest existential threat to springer survival on rivers from California’s Sacramento north to the Columbia. But bringing down dams is also symbolic on another level: in removing barriers that threaten Indigenous cultures and ways of life.

Removing dams, and rooting salmon management in Indigenous knowledge and conservation science: this is how we save spring Chinook and restore balance. Charley Reed’s elders know this. It’s time to heed their wisdom and bring the springers home.

“From the Spawning Ground” celebrates the return of spring Chinook on the Klamath’s South Fork Salmon River. Film by Thomas Dunklin, poem and songs by Karuk artist Brian D. Tripp.

Spring Chinook Series | Part I | Part II | Part III | Part IV

Hero Image