The director of the Natural Capital Project and Stanford University professor reflects on forging big actions from small steps and a shared sense of place.

Dr. Mary Ruckelshaus is a keen surveyor of landscapes.

There’s the DC political landscape, practically a birthright for her and her siblings. In 1970, father William Ruckelshaus, an Indiana attorney and congressman, became the first administrator of the new Environmental Protection Agency.

Relocating to Seattle as a teenager, Mary climbed deep into the Cascades while working summers with the Youth Conservation Corps in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness between Stevens and Snoqualmie Pass.

“I loved DC, and getting to feel the pulse of government,” she says. “But the Northwest is home for sure. Those real wild mountains, I just never came back from that.”

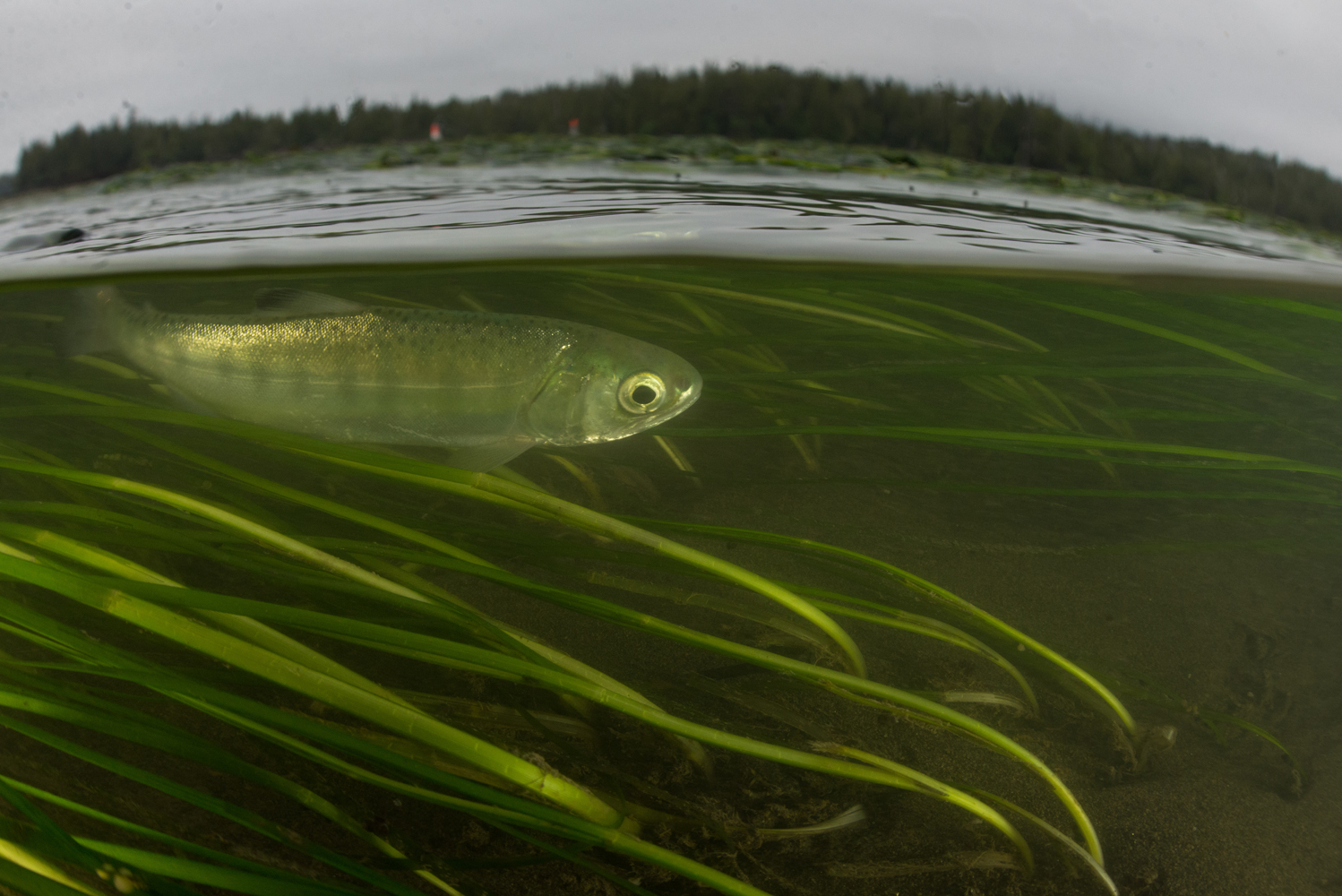

Then there are the seagrass meadows off San Juan Island, which fascinated her as a doctoral candidate. Immersed in this underground forest, she saw the complexity of these marine systems, which connect species from sea stars to Salish Sea killer whales.

“I’d go home after work, grab my dog, and watch sunsets with a snack,” she recalls. “And I’d almost always see the whales. It was a given, a big part of my experience. And I knew that they were there for the salmon.”

This past year, Dr. Ruckelshaus—director of the Natural Capital Project and a consulting professor at Stanford University—joined Wild Salmon Center’s board of directors, a position to which she brings both her personal love of nature and a deep well of professional experience. (She also serves on the Nature Conservancy’s science council and is a member of the United Nations’ High Level Panel on Building a Sustainable Ocean Economy.)

Below, Dr. Ruckelshaus shares more about the connections that drive her work and life, from the hard work of salmon recovery to the home waters that can motivate all of us.

Dr. Mary Ruckelshaus, in her own words:

I’ve always loved nature. As an undergrad, I worked summers on the Pacific Crest Trail as part of the Youth Conservation Corps. But it was when I learned how to scuba dive that I felt my mind open up—parts of my mind that weren’t otherwise apparent to me. Just being able to see what it looked like down there.

My first love of science came from what it felt like to be out there in the natural world. It was love that made me want to understand it better. That’s what drew me into science. I definitely entered this field from an emotional place.

My research started as purely ecological: what are plants and animals doing, how are they interacting. But then I started studying how the state of nature impacts people’s well-being. It was coming full circle: how our attitudes and mindset affect the state of nature, and vice versa.

I feel incredible admiration for salmon. The way they go about their life history, how they go through this incredible journey, this gauntlet, to get out into the ocean, and back. The great thing about research in seagrass meadows is that, unlike deep-water scuba diving, you can stay in the shallows for a long time. You can just watch juvenile salmon move around, like in a forest. You can watch up close and personal, and see how industrious and creative they are.

In seagrass meadows, you can watch juvenile salmon up close and personal, and see how industrious and creative they are.

Over the course of my career I’ve come to learn how intertwined salmon are with the lives of people in Salmon Nation. It’s so rich and inspiring to think about how intertwined Native communities have been with salmon for so long.

In my ten years at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [Editor’s note: Dr. Ruckelshaus previously led the Ecosystems Services Program at NOAA’s Seattle-based Northwest Fisheries Science Center], I worked with many stakeholder groups throughout the Pacific Northwest, much of that in Puget Sound and the Columbia Basin.

In Washington State we worked on salmon recovery with the 21 Treaty Tribes in Puget Sound as well as businesses, local governments, watershed councils, and 16 counties. We asked, what would be a recovered salmon run in your watershed?

These representatives—who were not only stakeholders but also affected by this—they came up with what they would do to achieve the science-based goals. What would they commit to? I worked on that process for about five years and it was transformative for me, because I saw all the ways that people care. They might have different entry points, but they do care. And those different entry points strengthen the conversation, and build toward a greater good, a shared vision around salmon.

People might have different entry points, but they do care. And those different entry points strengthen the conservation, and build toward a greater good, a shared vision around salmon.

It’s an art to get all those people to that place. It’s a conversation, a connection, and a building of trust. That’s what works. But it takes vigilance and determination. You can’t just do it once. We can’t just say, okay we all love salmon, so let’s do these ten things and call it done.

That’s a big part of why I’m excited to become a part of Wild Salmon Center’s stronghold approach, which focuses on durable outcomes that don’t just stop with getting protections for one part of a watershed. It’s about getting people to become the true stewards of their watersheds. Getting people who care, or are invested, or hopefully both, to internalize the value that their watershed brings to them and their communities. So that they know it in their deepest soul and that permeates their decision making.

Certainly there are things beyond our control. But if we can get back to that idea of stewardship, get people to see their vested interests, then that is a hopeful thing. I believe we can give salmon a fighting chance.

If we can get back to that idea of stewardship, get people to see their vested interests, then that is a hopeful thing. I believe we can give salmon a fighting chance.

Mary Ruckelshaus is the director of the Natural Capital Project and a consulting professor at Stanford University. She has also led the Ecosystem Science Program at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle. And before that, she was an assistant professor of biological sciences at Florida State University. The main focus of her recent work is developing ecological models including estimates of the flow of ecosystem services and changes in human wellbeing under different management regimes around the world.

Mary serves on the science council of The Nature Conservancy and is a trustee on its Washington Board. She is also a member of the U.S. Ocean Research Advisory Panel—charged with providing independent science advice to the National Ocean Council and is a past chair of the Science Advisory Board of the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis. She was Chief Scientist for the Puget Sound Partnership—a public-private institution charged with achieving recovery of the Puget Sound terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems. Ruckelshaus has a bachelor’s degree in human biology from Stanford University, a master’s degree in fisheries from the University of Washington, and a doctoral degree in botany, also from the University of Washington.