For fans of wild salmon, it’s hard to know what’s the right choice in a restaurant or at a store. Here’s why sustainable seafood purveyors like Patagonia Provisions are stocking Lummi Island reef-netted salmon.

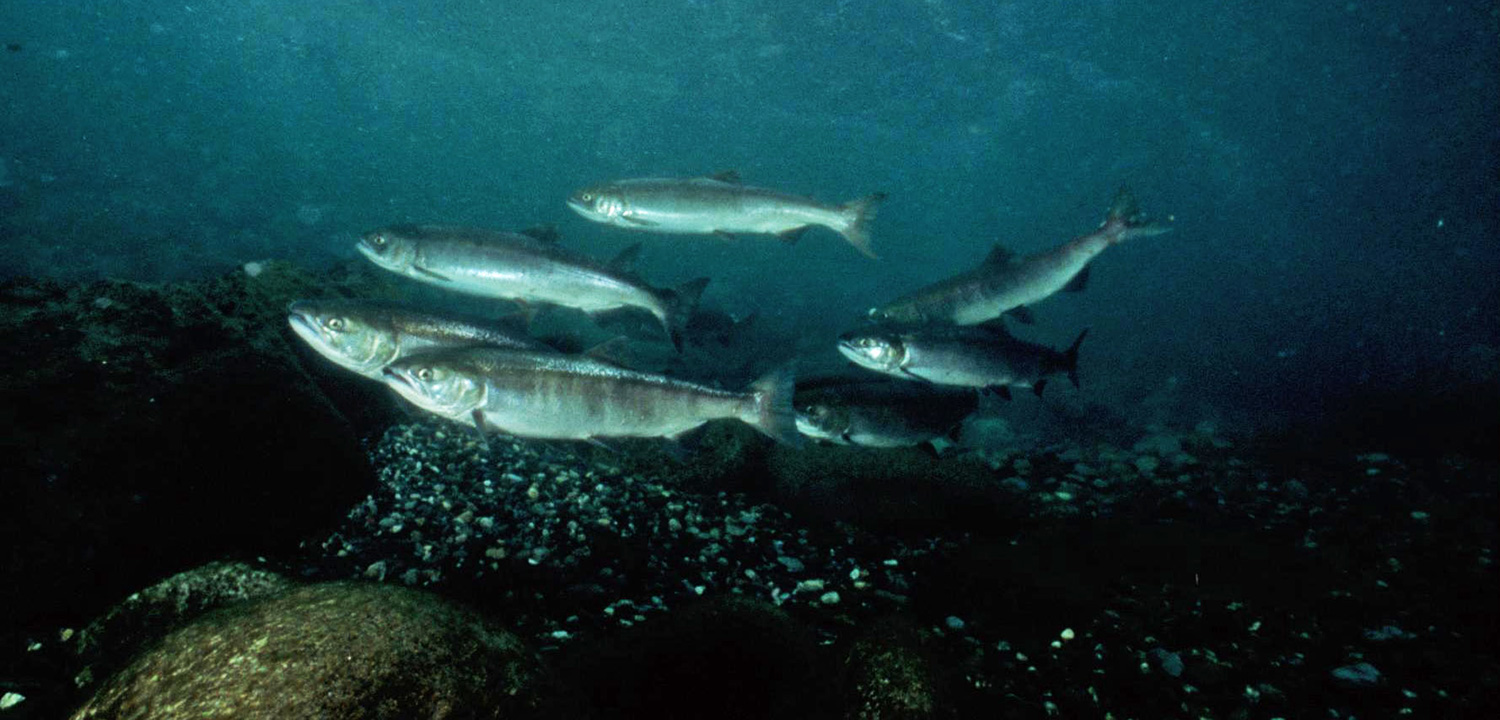

Most summers, Washington’s Southern Resident orcas round Vancouver Island and follow the Haro Strait, just west of the San Juan Islands, chasing after home-migrating Fraser River salmon.

But as hungry orcas hunt the western Salish Sea, some salmon runs flow east, through areas where the families of the Lummi Nation have fished for generations.

It’s a heartbreaking fact that the Salish Sea’s salmon runs aren’t nearly as abundant as they once were, along with the orcas that eat them. For some, that prompts talk of simply shutting down commercial salmon fisheries. But according to Ellie Kinley, a lifelong fisher and Lummi Nation citizen, that sort of sweeping action helps neither salmon nor orcas.

“I think there’s a lot of miscommunication out there when it comes to buying and eating salmon,” says Kinley. “We’re catching salmon in a terminal area. They’ve already passed through where our Southern Residents can eat them.”

Instead, Kinley says, people should be celebrating the salmon that her family sells through brands like Lummi Island Wild and Salish Select. If you can find these salmon products at stores, she says, then you know that it comes from a fishery that is strictly managed to meet escapement goals. That means that before any fishing season opens for her family, several international agencies must first agree that enough spawning salmon have entered the Fraser River to maintain population targets.

“The beauty of fishing [like we do] is that we never get to fish unless enough fish go up the river,” Kinley says.

But multi-agency sign-off is just one reason why Kinley feels that conscientious diners should seek out her salmon. There’s also her family’s leading role in helping to drive a resurgence, here near Lummi Island, of reef net fishing: a traditional selective fishing technique that the Kinleys and others are now using as a way to harvest more abundant returning sockeye and pink salmon runs without harming vulnerable stocks—like the Fraser River Chinook that comprise a large part of the diet of Southern Residents orcas.

For millennia prior to Western contact, Coast Salish families fished river systems like the Fraser, Nooksack, and Skagit with selective fishing techniques like pound nets, weirs, wheels, and beach seines. Specific reef net sites, generally located near river mouths, were handed down through generations of families living on or near the San Juan Islands and north to the Saanich Peninsula.

“The Coast Salish people invented reef netting,” says Riley Starks, the founder of the 15-year-old seafood processor Lummi Island Wild and a lifelong crab and salmon fisher. “It’s a very humane and kind way to catch salmon.”

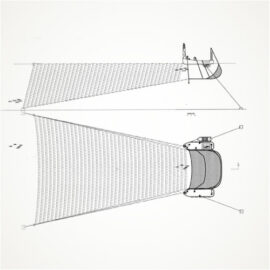

The technique, Starks explains, is a simple one—two boats anchored in the water, holding a large, submerged net between them at the lip of an artificial reef—traditionally made of stinging nettle bush and wild grasses. The reef passively funnels fish up and over to the net, and into the view of the fishers in the boats. Once fish are spotted, the net is lifted to just below the water line, and fishers hand-sort the catch.

“As a fisherman, when you want fish for yourself, you only want the highest quality,” says Starks. “With reef netting I could see how they handled the fish: you pick them up one at a time, you bleed them, you put them on ice right away. There’s very little trauma, there’s no unwanted mortality.”

By the early 1990s, Starks had bought his own reef net. Soon after, he met Ellie Kinley’s late husband Larry Kinley, a Lummi Nation elder with a vision for reconnecting his community with reef netting. Once the dominant fishing technique in these waters, traditional reef netting had been largely abandoned by Coast Salish families over the past several generations—and not by choice.

That’s because back in 1897, California canning bosses convinced the Washington State Legislature to make reef nets illegal. These bosses quickly built canneries and pound nets near reef net sites managed by Coast Salish families for millennia, and zealously enforced the new reef net restrictions.

This pressure forced Indigenous communities to adopt different techniques to continue their fishing way of life. Today, for example, Ellie Kinley’s sons and other relatives help crew a family purse seiner and gillnet boat; reef netting, for them, is a new practice, one that they’re improving with modern fish tracking technology and other tools.

“Before he died three years ago, Larry Kinley said that ‘reef netting is the center of our culture and we must reclaim it,’” Starks said. “My guess is that in the next 20 years we’ll see more and more reef nets pop up. It’ll happen in the very slow, methodical way that Indigenous communities work.”

Helping to boost the use of reef nets are new fishing businesses that focus on revitalizing these traditional practices, including Lummi Island Wild and, now, Salish Select. Together, the companies work with about 12 reef nets—one of them owned by the Kinleys—and also partner with the Snohomish Tribe and Upper Skagit Tribe to source salmon selectively harvested via other traditional practices, like beach seining.

And demand is surging from vendors like New Seasons, where Lummi Island Wild smoked sockeye sells out fast. Patagonia Provisions, another big retailer, keeps upping its annual orders of Lummi Island reef netted pink and sockeye salmon. The purveyor, which has built its brand on sourcing and processing only regenerative, organic, and sustainable foodstuffs, is clearly a fan; product descriptions for its Lummi Island-sourced products—like pouched black pepper wild pink salmon and lightly smoked wild sockeye—open by proudly highlighting that they’re responsibly harvested.

But reef netting is still a small fishing community. Between that limited capacity and the fishing pressure on salmon runs further out at sea in mixed-stock fisheries, Lummi Island’s reef netters can’t always fill the orders they receive. The answer, Starks says, is reviving the Indigenous selective fishing practices that were once so widespread here, and helped maintain healthy fish populations for millennia.

“Twelve reef nets—it’s not enough,” Starks says. “This should again be the dominant fishing technique in the Salish Sea. The more I’ve seen what’s happened in the Salish Sea, the more I realize that reef netting has to be the future or we’re not going to be able to have a salmon fishery here.”

It’s a move that might make for many happy customers in the future, including those hungry Southern Resident orcas circling just a few clicks west.

WHAT IT IS: Reef netted wild pink, chum (keta), and sockeye salmon is harvested by a small community of Indigenous and non-Indigenous fishers near Lummi Island in the northeastern Salish Sea.

WHY IT’S KEY: Once the dominant fishing practice of Coast Salish people near Lummi Island, reef nets allow fishers to selectively harvest only target runs and release bycatch with minimal trauma and zero time out of water.

WHERE TO FIND: Reef netted Lummi Island salmon products are offered through brands like Lummi Island Wild and Salish Select and retailed by purveyors including New Seasons and Patagonia Provisions.