Nine months of high stakes negotiations bore fruit on October 30, with timber interests and conservation groups backing big improvements to the state’s Forest Practices Act.

In the wee hours of Saturday, October 30, history was made for Oregon forests and salmon rivers. After nine months of difficult negotiations—preceded by many additional months of work to bring all parties to the table—13 timber representatives and 13 conservation and fishing groups reached an unprecedented conservation agreement on the Private Forest Accord.

The agreement proposes an overhaul of the Forest Practices Act to better protect wild salmon streams on more than 10 million acres of private Oregon forestland. The changes would dramatically improve the state’s forestry rules, long considered the weakest on the West Coast. And they represent a huge step forward for climate-smart forestry, particularly in safeguarding the cold, clean water that Oregon’s wild fish will increasingly need.

The negotiations were closely shepherded by Governor Kate Brown, including during Friday’s final marathon negotiations. The agreement now advances to the legislature to be codified into law; following that, a plan will be developed to present to federal fish and wildlife agencies for final approval under the Endangered Species Act.

“There is a lot in this deal,” says Wild Salmon Center Oregon Policy Director Bob Van Dyk, who led negotiations from the conservation side of the aisle. “Let me say we tried to get a lot more, and made some painful compromises. But on the whole, we decided to agree, because we all recognize that constant gridlock serves no one: not the timber industry, and certainly not Oregon’s forests, fish, wildlife, and communities.”

Here are the agreement’s big-ticket items:

STREAM BUFFERS

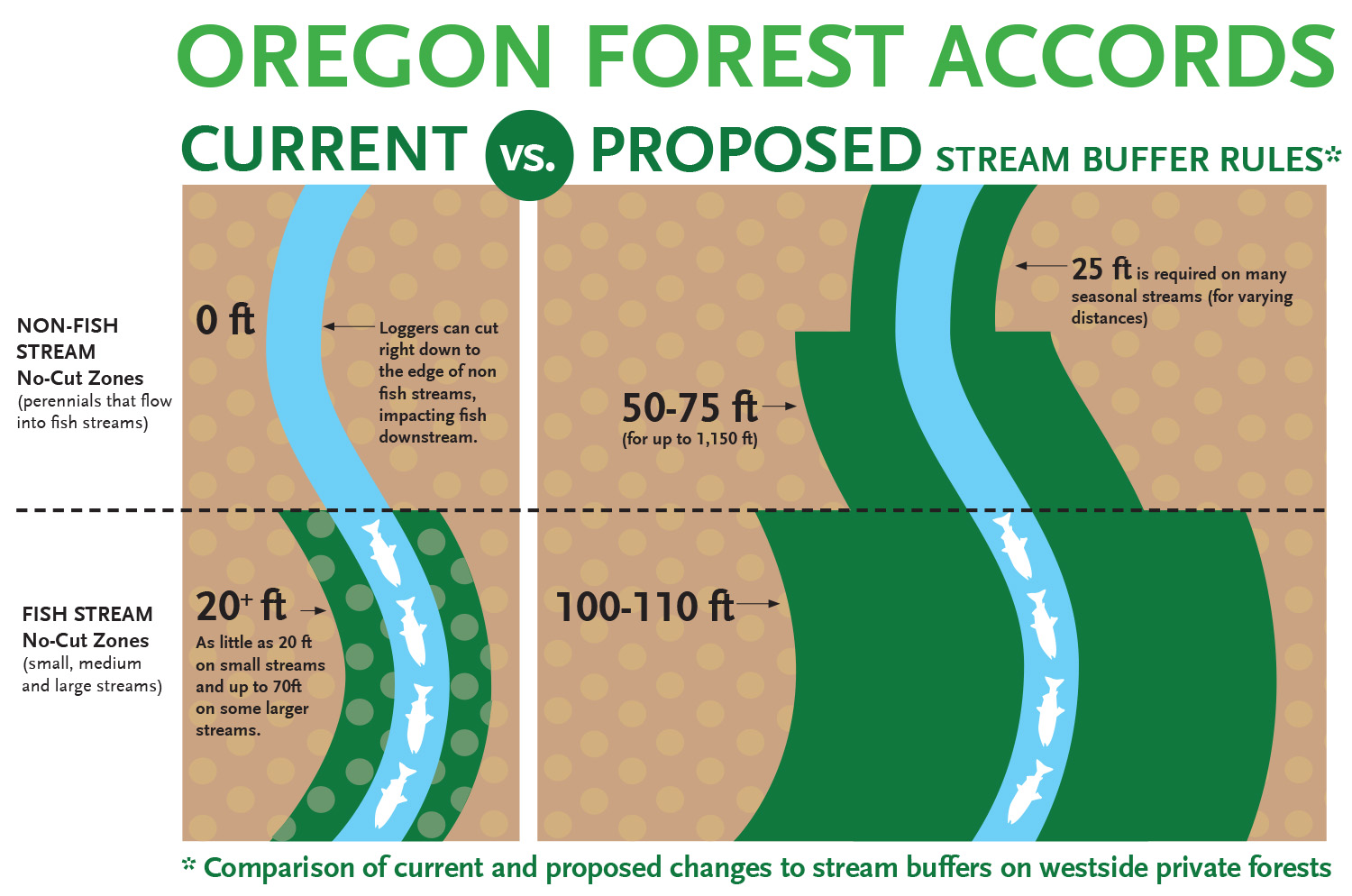

The agreement would significantly expand streamside buffers: forested strips where little or no logging can occur, in order to keep water cool and free of sediment.

For Western Oregon, proposed changes would increase buffers to 110 feet on large and medium fish streams, and 100 feet on small fish streams. (For reference, current minimum buffers on small fish streams range from 20-25 feet.) On designated large and medium non-fish perennial streams, buffers would increase to 75 feet.

The really big changes, Van Dyk says, apply to streams currently without buffers, including on small “non-fish perennial” tributaries that flow into salmon and steelhead streams. The agreement proposes a minimum 75-foot-wide buffer along the first 500 feet of these streams, winnowing slightly to a 50-foot-wide buffer for the next 650 feet for 1,150 total feet of new protection.

These and other improvements to logging along headwater tributaries will help keep stream networks from warming, and ensure that more large, habitat-making tree debris will flow downstream.

“We’re especially pleased with these changes, which promise more wood for fish habitat and other wildlife, cooler water, and a lot of carbon storage, too,” Van Dyk says.

It’s tricky to calculate the total stream miles that would receive new or increased buffers through this plan, he says. A likely estimate is tens of thousands of stream miles—possibly as many as 60,000—across the 10 million acres covered by the agreement.

ROADS

Another set of proposed big changes impact roadways on private forestland. Failing roads are one of the main culprits in dumping sediment into streams, which can ruin water quality. According to Van Dyk, highlights from some 20 pages’ worth of new proposals include:

- New requirements for all large landowners to inventory their roads over 20 years and ensure these roads meet new standards.

- Strong commitments to upgrade culverts, provide fish passage, and build to new standards for flow and fish passage that reflect the more frequent flooding occurring with climate change.

- A “strong and focused” effort to ensure all roads are engineered to steer runoff away from streams.

- A commitment to using the latest technology (like LiDAR) to find and address abandoned roads.

STREAM TYPING

“It turns out it can be hard to figure out whether fish use a particular stream, because fish are crafty and move around,” Van Dyk says. “It’s also hard to know whether a given stream flows all year, because of yearly weather variations. But these things really matter, because they affect the type of buffer that stream gets.”

According to Van Dyk, “stream typing” can be a hornet’s nest of controversy, so he’s proud of the progress made in the Accords. In short, both sides agreed that the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife, rather than the Oregon Department of Forestry, will become a central keeper of stream typing data, and the latest and best science and technology will be used to build, test, and rationalize this information.

SMALL FORESTLAND OWNERS

Oregon’s small forestland owners hold much of the state’s best salmon habitat in their lowland properties, and this deal makes some big changes for them. These changes include:

- The creation of a significant new office dedicated to outreach and support for Oregon’s small forestland owners.

- New minimum standards for timber harvest on these properties that are: 1) lower than the standards for larger private owners, but 2) come with strong tax credits to reward owners who choose to follow these new standards.

- Requirements that small forestland owners provide data on fish passage and road conditions if they want to harvest on their properties.

- A new commitment to increase state subsidies for small landowners who upgrade fish passage and roads on their property.

COMPLIANCE MONITORING AND ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT

Monitoring of Oregon forest practices hit a low ebb in 2019 when an audit found that the state had no adequate tracking mechanism for how companies were complying with forest laws.

“Compliance and adaptive management might sound boring,” Van Dyk says, “but this important area gets a complete—and necessary—overhaul in the agreement.”

The overhaul starts with the creation of a new, diverse, and well-funded stakeholder body to direct science work. The agreement also establishes that an independent science team will conduct studies and report them to the Board of Forestry.

The agreement reforms some current compliance problems, such as improving state access to private forestland. According to Van Dyk, under current law, representatives of the state are not allowed to enter a landowner’s property without permission to assess if public resources are protected when harvests occur.

“Hire a contractor to add an outlet in your kitchen, and you’ve got to allow the government inspector to check,” he says. “But if you want to clear cut thousands of feet near fish-bearing waters? You can just say no to an inspection. That scenario is over.”

BEAVERS

The scientific community has come to recognize the critical role that beaver dams play in supporting many wildlife species, including salmon. The Accord outlines new rules that reflect this knowledge, including a requirement that all beavers killed on private forestland be reported to ODFW.

“We’ve needed this for a long time to get basic population monitoring,” Van Dyk says.

The agreement language also prohibits commercial trapping of beaver on large private forest ownerships, prioritizes non-lethal strategies for addressing beaver conflicts on forestlands, and establishes that ODF will participate with ODFW in a voluntary relocation program.

NEW MITIGATION FUND, AND MORE

There’s much more inside this historic agreement, Van Dyk says—not least of which is an annual commitment from landowners ($5 million) and the state ($10 million) to a 50-year fund to help improve habitat and protect water quality.

For all the hugeness that the Accord represents—the end of decades-long gridlock between timber and conservation interests—there’s still more distance to cover in this marathon endeavor, starting with legislative approval. Still, this historic moment certainly calls for reflection—and celebration.

“I may have been the de facto leader for the conservation side, but there is a long list of policy, scientific, and legal experts who made this happen,” says Van Dyk. “There are a lot of thanks yous to make.”