New research from scientists including WSC’s Dr. Matt Sloat suggests that protecting genetic diversity could help save the world’s largest salmonid.

Over time, rivers merge and diverge, carve paths through new mountains and recede completely. These changes can be glacial. They can also happen fast: with a flood, a landslide, a seismic or volcanic event.

Taimen, the world’s largest salmonid, have survived these shifts for tens of millions of years, their adaptations imprinted in DNA. Through genetic science, we’re now able to read more of their epic saga. This knowledge illuminates the past. According to Wild Salmon Science Director Dr. Matt Sloat, it can also guide conservation actions for the increasing volatility of today’s climate.

In a new research paper published in Nature Scientific Reports, Dr. Sloat and a team of scientists analyzed Siberian taimen DNA from three remote Russian and Mongolian river systems: the Tugur, Amur, and the Arctic-flowing Yenisei. The paper is a critical addition to the limited body of research on this imperiled apex predator. And it holds fresh insights for conservationists working to ensure that taimen survive the challenges of modern climate change.

The paper is a critical addition to the limited body of research on this imperiled apex predator. And it holds fresh insights for conservationists.

“As the number of taimen populations declines, we risk losing the genetic diversity that will help this species cope with climate change and other challenges.” says Dr. Sloat. “Our work documents the genetic diversity in some of the last best taimen populations on earth, providing a much needed baseline that can be used to assess the genetic health in other populations.”

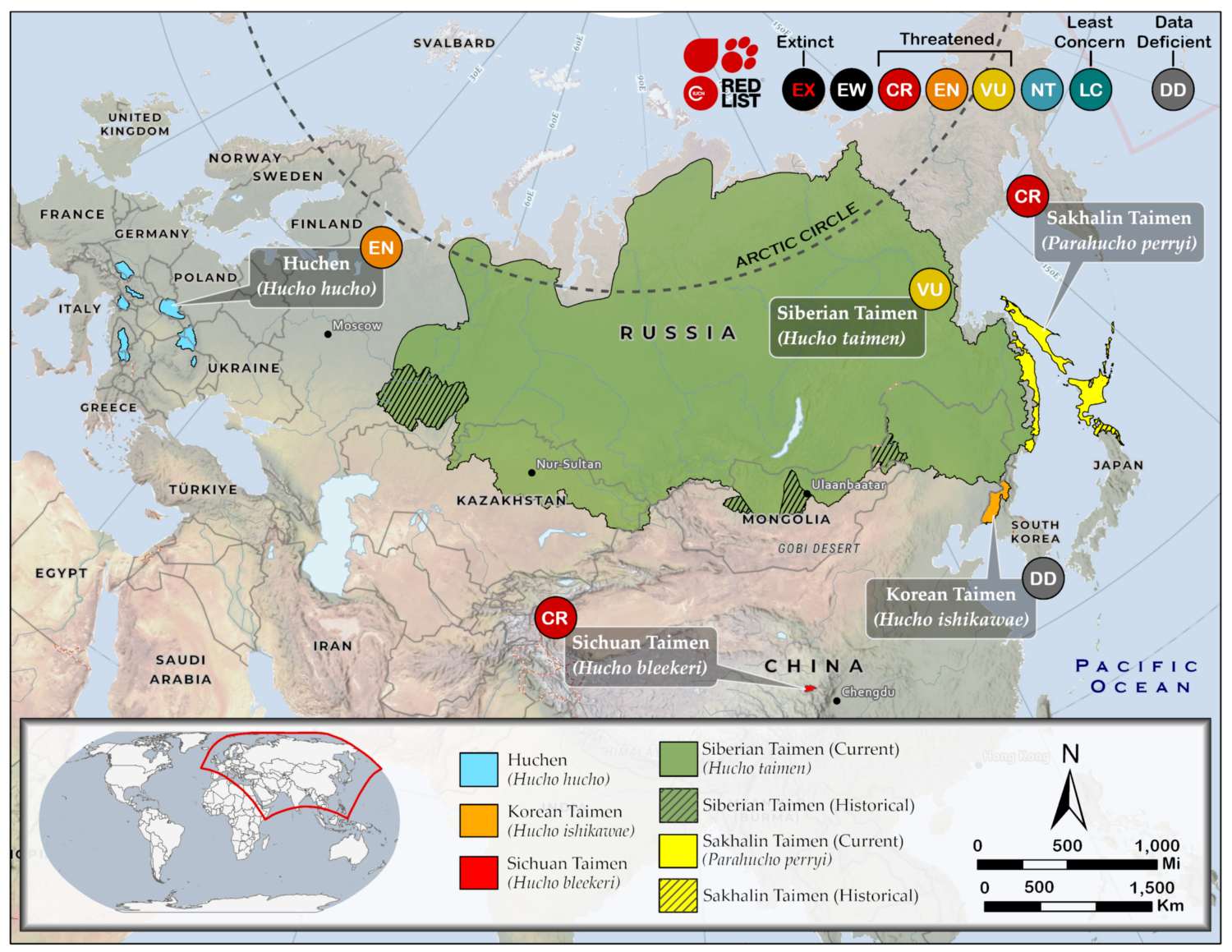

A key takeaway for conservation scientists is the critical role that taimen genetic diversity might play in efforts to protect the species across its historic range. That range is vast—covering one-tenth of the world’s land surface—and varied. Taimen are native to rivers from the Mongolia steppe to salmon watersheds in the Russian Far East.

The new research finds that taimen from different watersheds have diverged over time and become locally adapted. The patterns of taimen evolutionary history can help conservation, Dr. Sloat says, by facilitating comparisons across populations and identifying early signs of genetic diversity loss.

“Taimen genetic diversity remains unmeasured over most of their range,” he says. “We now know that for the taimen rivers we studied, that they have healthy levels of genetic diversity— and diversity was unexpectedly high in the Tugur. But we need to know much more about this species to protect that diversity across the vast area where we find them.”

“Taimen genetic diversity remains unmeasured over most of their range,” Dr. Sloat says. “We need to know much more about this species to protect that diversity.”

Unlike other salmonids, Siberian taimen are not ocean-going. They live their entire lives—as long as 40 years—in headwaters and upper watersheds, feeding on grayling, lenok, salmon, and other prey that enters these high reaches. And they’re a hard species to study, due to taimen’s characteristic elusiveness and the ruggedness of their habitat.

Through field work and outreach over years, Dr. Sloat and his partners collected samples from multiple sites within the Tugur, Amur, and Yenisei watersheds. Analysis of these samples revealed clear genetic differentiation between each river’s taimen population: the product of time, seclusion, and that system’s unique combination of prey access, topography, and climate conditions.

In some cases, the genetic patterns might even show us the maps of the distant past. Take the case of the Tugur River, where Dr. Sloat says his team found a genetic divergence between the taimen populations of its mainstem and tributaries.

“Siberian taimen don’t migrate through the ocean, so their spread throughout this vast region took a very, very long time, as rivers came together and then separated and changed their course over millenia,” says Dr. Sloat. “The most plausible explanation for two distinct populations in the Tugur is that at least twice in the past—if not many times—the Amur River merged with it and allowed fresh colonization of the basin.”

It’s no surprise to us, of course, that rivers change course, carve new paths, and vanish. Even as we know that rivers are mutable, it’s human to think of our modern-day maps as static. Yet the world’s rivers are changing right now, before our eyes. Across the North Pacific, salmon rivers are hotter, drier, and increasingly volatile; the glaciers feeding many are melting, presenting both threats and opportunities in the form of potential new habitat.

If taimen are to survive in the systems where we still find them, we need to understand what’s enabled this mysterious salmonid to thrive over so many millennia. For Dr. Sloat, that starts with building a more robust genetic baseline—a fuller picture of local adaptations and evolutions across many taimen rivers.

“Our work in this paper just scratches the surface,” he says. “The next step is to go deeper on this research. It just might give us the tools to help taimen maintain their adaptive potential, like the ancient survivors we’re learning they are.”

If taimen are to survive in the systems where we still find them, we need to understand what’s enabled this mysterious salmonid to thrive over so many millennia. For Dr. Sloat, that starts with building a more robust genetic baseline.

Hero Image

Hero Image (Home Page Section)