To protect wild salmon biodiversity, we need accurate fish counts in real-time. With our partners, we’re developing a game-changing technology solution.

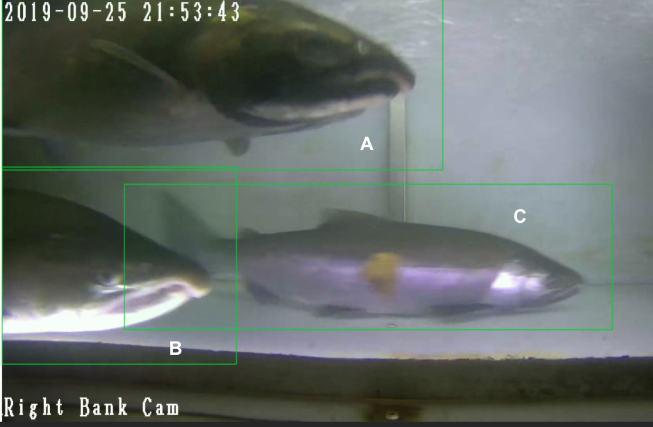

From the Yukon south to California, some high-tech gadgets are silently working from the banks of certain salmon rivers. Some are specialized sonar systems, beaming through the water column during the fish’s return to freshwater. Others are video cameras in waterproof housing, mounted inside fish weirs and wheels to monitor underwater river traffic.

When a migrating salmon or steelhead passes through sonar fields of vision, that information can ultimately be translated to video, much like the underwater footage captured by traditional cameras mounted in fish weirs.

To human eyes watching either form of footage later, these wiggling squiggles are recognizably fish. Informed observers can mark each one down by species, sex, and more, with few confident ticks in a ledger or spreadsheet.

Accurate fish counts are essential for fisheries managers across the North Pacific, who use this information to set harvest rates and track measures taken to meet escapement quotas. But many high-tech sonar and video systems—big investments for cash-strapped public agencies—are missing a crucial element: enough human eyes to watch the footage and count the fish.

“Right now, there are dozens of sonar and video systems out there in salmon rivers,” says Wild Salmon Center Scientist Dr. Will Atlas. “But much of this data is never used, simply because no one has the time or resources to go through thousands of hours of fuzzy video.”

Enter the Salmon Computer-Vision Project, a new collaboration between WSC, the Pacific Salmon Foundation, Simon Fraser University, 12 First Nations, and multiple government agencies.

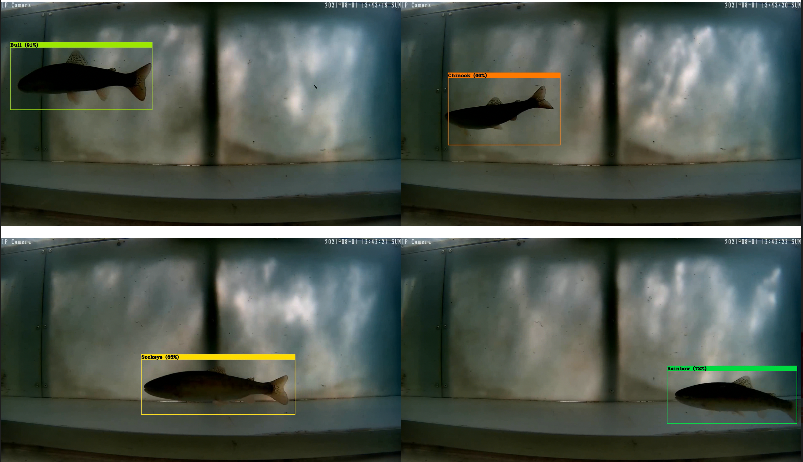

According to Dr. Atlas, the group is using machine learning technologies to teach computers to recognize fish on video and create accurate counts on our behalf—saving human eyeballs, and providing fisheries managers with the data they need to better protect wild fish diversity across the North Pacific.

For wild salmon and steelhead, this project comes at a critical time. Right now, many fisheries managers on the west coasts of the U.S. and Canada don’t have exact data on the runs they manage—let alone as these fish are actively passing through fisheries to reach spawning grounds.

“If we’re going to ensure that these species remain robust enough to buffer against the growing impacts of climate change, we have to protect a broad diversity of runs,” Dr. Atlas says. “We can’t maintain critical biodiversity and also keep fisheries open without real-time information on how these runs are doing.”

“We can’t maintain critical biodiversity and also keep fisheries open without real-time information on how these runs are doing.”

WSC Salmon Watershed Scientist Dr. Will Atlas

But without someone—or something—to watch footage and count fish, these expensive tracking systems can’t deliver this vital information to fisheries managers.

The consequences of this data gap are already hitting home, says Dr. Atlas. He points to the recreational salmon fisheries off the Central Coast of British Columbia, where Canada’s Department of Oceans and Fisheries (DFO) sets bag limits on daily catches before the fishing season begins.

“Too often, we’ll learn after the fishing season is over that DFO’s forecast was far too rosy,” Dr. Atlas says.

When status quo fishery management is maintained throughout a fishing season in years when runs are struggling, he explains, then we’re continuing a vicious cycle of overfishing runs that are often already in decline.

“If we were analyzing the data that we’re in many cases already collecting in a timely fashion,” he says, “then we could be adjusting those bag limits in real-time, while we can still make a difference for these fish.“

The technology to do this work already exists in adjacent spaces, he says. Machine counting using visual pattern recognition technology has been deployed in other wildlife conservation settings—to analyze wildlife trap camera data, for example—but has been slow to reach the world of salmon conservation.

“We know what needs to be done to fix this data gap for fisheries managers,” Dr. Atlas says. “Our team is small but making progress. We’re now advancing into software development. It’s also true that this work could go even faster with more tech and philanthropic partners.”

“We know what needs to be done to fix this data gap for fisheries managers. It’s also true that this work could go even faster with more tech and philanthropic partners.”

WSC Salmon Watershed Scientist Dr. Will Atlas

At the current pace, Dr. Atlas and his team say they’re about two to three years out from a formal product launch. When released, they hope to offer open-source software capable of accurately recognizing and counting migrating fish, along with a free, user-friendly software interface through which fisheries managers can upload and analyze their data in real-time.

“Our goals are very achievable,” Dr. Atlas says. “We’ve already proven the concept in British Columbia watersheds like the Koeye and Kitwanga, where our model achieved greater than 95 percent accuracy for recognizing and counting returning salmon.”

With the baseline computer-vision software already written, Dr. Atlas and his team are now using machine learning to train up computer models for different rivers, including the Bear River in the Skeena watershed, and the Taku and Alsek Rivers in the B.C. and Alaska transboundary region. Working out software kinks will take time, says Dr. Atlas, but should pay big dividends for both fish and fisheries managers when dozens of fish tracking systems already in place can finally realize their full potential.

According to WSC Federal Affairs Director Jess Helsley, the timing of this project comes at an inflection point for Pacific salmon and steelhead. In both the U.S. and Canada, public agencies are unlocking serious new funding for natural infrastructure and salmon conservation, even as ever more wild fish species approach threatened or endangered status.

“Our goals are very achievable. We’ve already proven the concept in British Columbia watersheds like the Koeye and Kitwanga, where our model achieved greater than 95 percent accuracy for recognizing and counting returning salmon.”

WSC Salmon Watershed Scientist Dr. Will Atlas

In the past, Helsley says, fisheries managers counted on salmonid runs including Washington Coast steelhead and B.C. Coast sockeye to stay abundant enough to buffer against overharvesting and insufficient escapement data. But those times are behind us, she says, pointing to grim trendlines for these species and more.

What gives her hope is a paradigm shift within many fisheries management agencies. Collectively with partners like WSC and others, these agencies are recognizing the need to expand how species biodiversity is incorporated into fisheries management—recognizing that a “portfolio effect” can help salmon and steelhead populations to sustain fishing pressure both now and in the future.

To protect this biodiversity, Helsley says, we need the kind of highly accurate, real-time data that the Salmon Computer-Vision Project hopes to unlock.

“Right now, we have the chance to give ourselves a lasting gift by investing in the tools to better understand salmon and steelhead,” she says. “Because the more we know, the more we can do to make sure these amazing fish are here for generations to come.”

“The more we know, the more we can do to make sure these amazing fish are here for generations to come.”

WSC Federal Affairs Director Jess Helsley

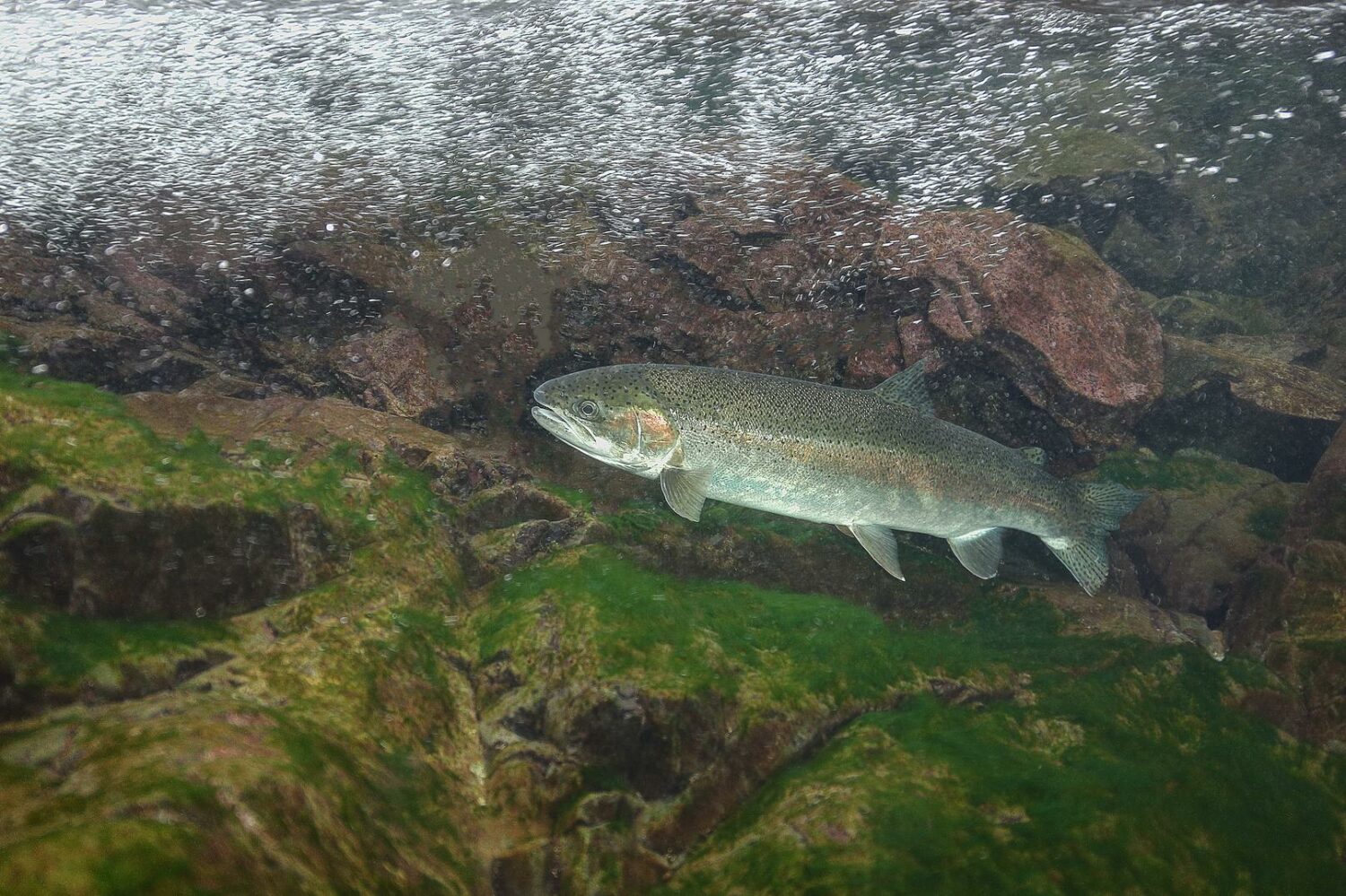

Hero Image