On a Wilson River tributary, a new future for Oregon’s state forests comes into view.

From an old hilltop logging road in the Tillamook State Forest, adventurers can catch sight of a long stretch of the Little North Fork of Oregon’s Wilson River.

For decades, this has been steep-slope logging country, a place where thick yarding cords still hang from ridgetops. But from this perch, you can also see a rare patch of old-growth in the near distance: remnant forest that survived last century’s Tillamook Burn wildfires.

According to Charles Wooldridge, a fisherman, photographer, and artist who’s lived in Tillamook County since the early 1980s, this intact habitat could be key to the future of Oregon’s once-lush North Coast forests, as one nucleus for their regeneration.

“The Little North Fork basin escaped much of the salvage logging and forestry practices we see nearby,” Wooldridge says. “Because of that, it still has healthy populations of wild fish, amphibians, and large game. Nature will move out and find a place, if you have that species health.”

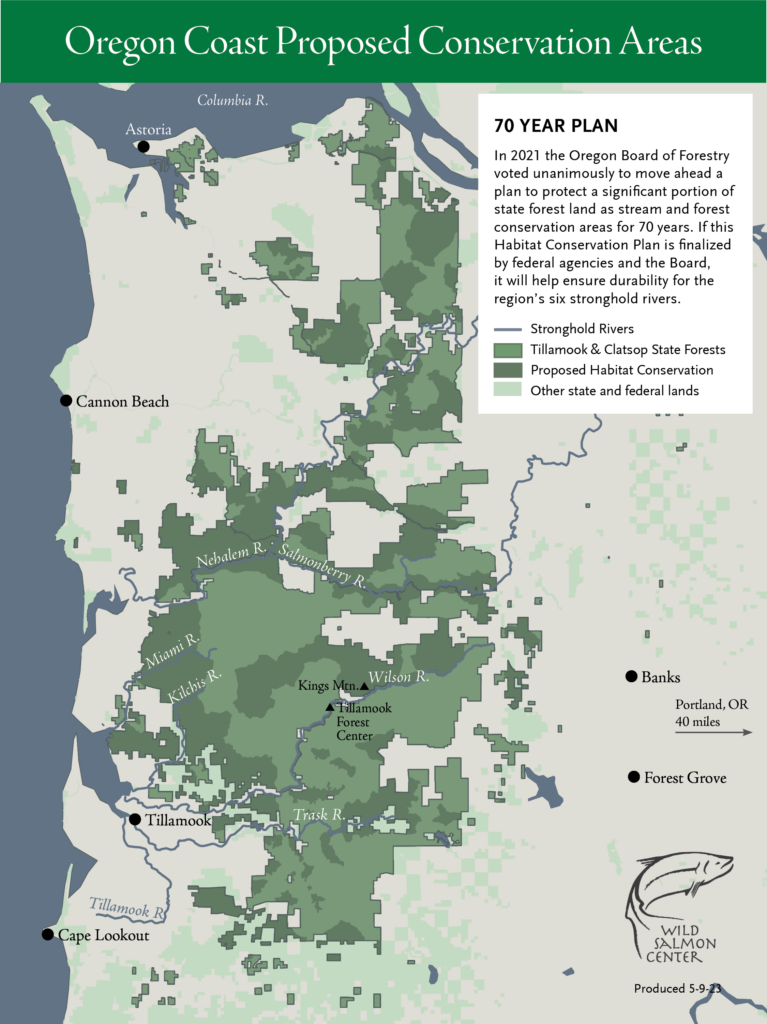

This year, these foundational populations of fish and wildlife could get a boost from a new habitat conservation plan under consideration by the Oregon Board of Forestry. If enacted, the plan would protect the Little North Fork’s precious old-growth stand within one of several dedicated conservation areas comprising roughly half of Western Oregon’s state forestlands. The plan’s conservation areas would transition 250,000 acres of the Tillamook and Clatsop State Forests from their current patchwork of clear cuts to a landscape that prioritizes fish, wildlife, and the human communities who rely on healthy forests.

Meanwhile, the plan would continue to manage another 250,000 public acres for timber production—with updated rules and more reliability, ensuring the long-term viability of a legacy industry for North Coast communities. For Wooldridge and others, it’s a compromise plan, but one that creates at least some room for North Coast forests to breathe again.

“After the Burn,” Wooldridge explains, “many counties wound up relying on the state to take care of the forest. But one thing they didn’t agree on back then is what a forest is. When you have species like yew, fir, and cedar that can live for hundreds of years, is it a forest if you keep logging it on a 30-year rotation?”

“One thing [the counties and state foresters] didn’t agree on back then is what a forest is. When you have species like yew, fir, and cedar that live for hundreds of years, is it a forest if you keep logging it on a 30-year rotation?”

Charles Wooldridge, fisherman, photographer, and Tillamook County resident

Wooldridge, who frequently uses the warren of old logging roads in his backyard to bushwhack deep into the Tillamook, seeks out these mature zones of alder and maple, giant remnant conifers, and steep slopes covered with tiger lilies, wild onions, and native succulents. He recalls seeing one ancient fir tree in this vicinity, somewhere near Stanley Peak. The massive tree was many centuries old, and the Burn had blackened one entire side, but it still produced seeds and cones, actively regenerating the landscape around it.

“The places back there in the coastal forest that have old-growth, they’re mysterious and inviting in the same way—primordial,” he says. “Even when I just drive by, I can imagine all these things are there. And that makes me happy. Though I’d be much happier if I knew these places would be left alone to function as large-basin anchor habitat on all levels.”

Wooldridge’s friend and sometime fishing buddy Bob Rees, Executive Director of the Northwest Guides and Anglers Association, has for years pushed Oregon’s Department of Forestry to advance the habitat plan toward a final vote, currently scheduled for sometime this year. Even now, representatives of the timber industry and some rural counties still try to derail the plan completely.

“We’ve already lost so much,” Rees says. “Take the industry I represent, which relies on the productivity of wild fish. We’re becoming an endangered species ourselves. But we can still move the needle for salmon. And a habitat conservation plan for state forests is a step in the right direction.”

Salmon and steelhead are keystone species, Rees reminds us—meaning that with productive salmon runs come productive wildlife populations and healthy landscapes that feed on the marine nutrients brought upriver by salmon. In many ways, he says, the Little North Fork of the Wilson is an ideal place to focus this ambitious, needle-moving conservation strategy.

Already, the Little North Fork is a big producer of the wild fish that drive work for Rees and his colleagues. It’s a “fish factory” for late-run fall Chinook. And it supports the mainstem Wilson’s relative abundance of Oregon Coast coho—an endangered species—as well as wild winter steelhead and cutthroat trout. Together with the neighboring Kilchis and Miami Rivers, the Wilson is also a rare stronghold of wild chum salmon: a species that’s all but disappeared elsewhere in Oregon.

“We can still move the needle for salmon. And a habitat conservation plan for state forests is a step in the right direction.”

Bob Rees, Executive Director of the Northwest Guides and Anglers Association

These fish runs are hardy holdouts, cherished by Rees and his fellow anglers. In nature’s interwoven way, these fish thrive in part because ancient and mature parts of this forest still exist inside this fractious landscape: canopies that shade streams, root systems that filter water and build food webs, and fallen trees that provide shelter for small fry.

This year, we have a chance to protect much of what makes the North Coast so special: from its wild fish runs to the primordial magic of its forests. Let’s make sure we win this plan for our public lands. And then, let’s transform the Little North Fork of the Wilson River into an anchor for the ancient forests, abundant wildlife, and wild fish of the North Coast’s future.