Lessons from the West could help inform a more fish-friendly future for Mongolia.

On a crisp mid-October morning on Northern California’s Klamath River, eight Mongolians peered over the rail of a ridgetop platform, taking in the spectacular view.

Far below the Mongolia delegation members—experts in aquatic ecosystems, biology, chemistry, and construction engineering—an arc of river flowed freely through a gentle gorge. Just months ago, the floor of this gorge had been 200 feet underwater.

It was a vista made possible by the absence of the 60-year-old Iron Gate Dam. The massive earthen wall once generated hydropower for thousands of households, but its usefulness had waned in recent decades. By the turn of the 21st century, Iron Gate—much like three even older dams immediately upstream—produced little energy. To stay in place, its private owners would need to invest in costly modern upgrades, including fish passage.

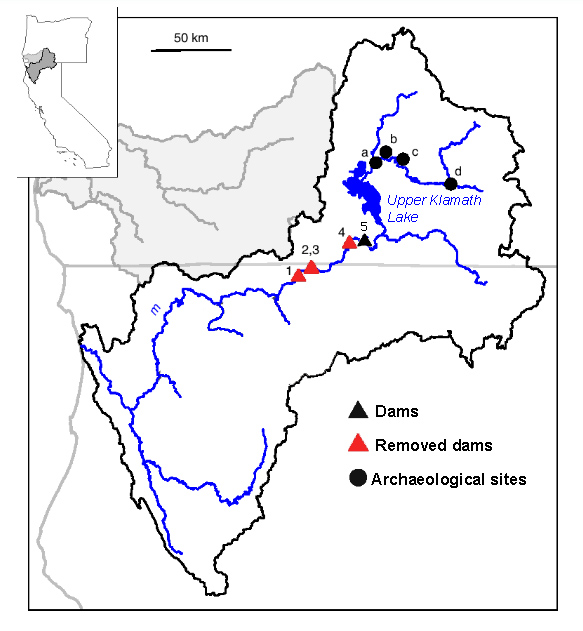

And so, starting in 2023, Iron Gate Dam and its upriver counterparts came down as part of the largest dam removal in history. The $500 million project stemmed from decades of activism and leadership from Tribes including the Karuk and Yurok, the active support of multiple governors on both sides of the Oregon/California border, and the formation of a new nonprofit entity, the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, to oversee the massive undertaking.

Far below the Mongolians, an arc of river flowed freely. Just months ago, the floor of this gorge had been 200 feet underwater.

With Iron Gate’s reservoir now gone, the Mongolian delegation could see the former dam’s namesake rock flanges on either side of the riverbanks. Sweeping up those banks, native seedlings were already taking root: willow and lupine, oaks and yarrow.

The Mongolian experts were here to ask big questions. As guests of a knowledge exchange hosted by Wild Salmon Center’s International Taimen Initiative, their presence here aimed in part to advance a global dialogue on how best to protect taimen, the world’s largest salmonids.

Mongolia is home to some of the most pristine and productive taimen rivers across Eurasia. But the nation is also looking for ways to sustainably develop and expand its domestic energy production. That drive for energy means that some of Mongolia’s most iconic taimen rivers are also now attractive locations for new hydropower dams and water storage infrastructure.

Which is why, this October morning, the Mongolian experts wanted to see firsthand what it looks like to dam—and undam—a salmon river. As one visiting Mongolian scientist explained: “We have to inform the decision makers.”

They put their questions to another expert: Toz Soto, program manager for the Karuk Fisheries Program. For years, Soto advocated for the Klamath dams to come down on behalf of his employer, the Karuk Tribe.

With dam removal underway this summer, Soto helped advise the Klamath River Renewal Corporation on how best to protect fisheries during the complicated deconstruction process. Now, the project was complete. Looking down at the newly free-flowing river, Soto told the Mongolian delegation that the sight “still takes my breath away.”

“This is the largest dam removal to occur in the world,” Soto reflected. “I think it sets a good precedent for us as humans when infrastructure is built, lives its life, and is removed. Dams are not permanent. And that can give folks that love rivers and salmon hope.”

“This is the largest dam removal to occur in the world. I think it sets a good precedent for us as humans when infrastructure is built, lives its life, and is removed.”

Toz Soto, Karuk Fisheries Program Manager

Taimen and Salmon: Headwater Lessons

When the Klamath dams went in, salmonid conservation science was in its infancy. Researchers didn’t understand the genetics that drive spring Chinook to climb higher in rivers than their fall-run cousins. Few knew that some salmonids make use of vast stretches of freshwater very early in life. And we hadn’t yet experienced the full costs of cutting off wild fish runs from their natal streams.

From 1913 until dam removal, the majority of the Klamath River Basin had been blocked to salmon. Three of the four dams built on the Klamath mainstem—Iron Gate, Copco No. 1, and Copco No. 2—were built without any fish passage at all. In recent decades, as Tribes and conservation groups pushed for dam removal, some opponents argued that salmon never migrated above Iron Gate. They claimed it was a myth that salmon ever made use of spawning and rearing habitat higher up in Klamath Lake and its tributaries.

When the Klamath dams went in, we hadn’t yet experienced the full costs of cutting off wild fish runs from their natal streams.

The Karuk and other Tribes, of course, knew this argument was false; they had oral (and photographic) history to prove that Klamath salmon migrated far into what is now called Oregon.

In 2017, genetic science caught up with Tribal knowledge. Research by current Wild Salmon Center scientists and others confirmed that both spring and fall Chinook did indeed travel hundreds of miles to reach the upper Klamath Basin—both in the distant past, and up until roughly the time of the dams’ construction.

The Klamath River mainstem stretches some 260 miles from its estuary near Crescent City, California, to Klamath Lake in Oregon. That’s already an epic journey for salmon. But genetic data show that Klamath salmon traveled all the way to spring-fed upper lake tributaries like the Wood and Sprague—through salt marshes and pine forests, shallows and cascades, algae-rich lake expanses and cold, steep mountain streams.

To take in the full scope of this vast pre-dam salmon habitat, the Mongolia delegation began their three-day tour 100 miles north of the Iron Gate. Here, in the uppermost reaches of the Klamath’s historic salmonid habit, Chinook salmon and steelhead haven’t been present for at least a century.

Standing by the banks of the gin-clear Wood River, Wild Salmon Center Mongolia Senior Manager Dr. Saulyegul Avlyush talked with other delegation members about conservation back home. In particular, they focused on how to balance the nation’s development needs with protections for Siberian taimen: an IUCN red listed species that international scientists are still struggling to understand.

The topic of wild fish conservation felt like a thread linking East and West. Like Klamath salmon, Siberian taimen and native species like lenok and grayling are long-distance travelers. And also like Klamath salmon, they rely on a wide range of habitats.

“We hypothesize that Siberian taimen make use of everything from headwaters and tributaries to large mainstem rivers, where they can hold in deep pools during iced-over winter months,” Dr. Avlyush says. “For taimen, I see parallels with Klamath salmon. It’s interesting for us to see how fish here used these systems before the dams, and how things changed for them when the dams went in.”

The topic of wild fish conservation felt like a thread linking East and West.

A Salmon Stronghold Dammed, then Free

Wild Salmon Center’s stronghold strategy holds that where salmon rivers are still healthy and intact, we must protect them as they are, before we lose ground. But across the West, many salmon rivers lost ground to development long ago. Direct intervention—habitat restoration and dam removal, for example—become necessary tools for salmon recovery. Profoundly altered rivers like the Klamath offer a powerful case study.

It’s been generations since Chinook salmon have made the journey all the way back to lake headwater rivers like the Wood and Sprague. And even with dam removal, the Klamath River remains altered. Above the 38-mile former reservoir chain, salmon still need to make it past the Keno and Link River dams at the lake outlet, and then across the vastness of Klamath Lake itself. But now, at least, that journey is possible.

“It’s exciting to think that salmon could make it back to places like the Wood River,” Dr. Avylush says. “But it’s also a good reminder for us in Mongolia to keep the needs of fish in mind from the very beginning when we consider our own development projects. That’s just one lesson we can take back home.”

Already, she says, conversations held during this knowledge exchange have catalyzed new plans for Wild Salmon Center and its partners in Mongolia, from habitat protections to fisheries management improvements.

“It’s exciting to think that salmon could make it back to places like the Wood River. It’s also a good reminder for us in Mongolia to keep the needs of fish in mind from the very beginning.

Wild Salmon Center Mongolia Senior Manager Dr. Saulyegul Avlyush

Proactive steps, and a growing body of conservation science, could help Mongolia improve the health outlook for salmonids and many other cherished aquatic species—along with the full diversity of habitats these species require for long-term survival.

In the Klamath Basin, a source of much of this new, internationally-cited science, there is growing consensus that to rebuild, salmon here must reclaim historic freshwater habitat above the dams. High on the list of potential game-changing salmon nurseries are the cold, clean, climate-resilient tributaries of the upper Klamath.

On the banks of the Wood River, standing next to Dr. Avlyush, Wild Salmon Center Science Advisor Dr. Jonny Armstrong—an influential expert in salmonid behavior and landscape ecology—pointed to a rich abundance of coarse gravel in the riverbed. One day soon, a Chinook hen could find her way here. And she might decide, like her ancestors did a century ago, that it’s the perfect place to build a redd.

History won’t repeat itself in a river system as altered as the Klamath. But with time and healing, it’s now possible that it could rhyme.

To rebuild, salmon will need to find their way back to historic freshwater habitat like the cold, clean, climate-resilient tributaries of the upper Klamath.

Global Questions: Development, Dams, and Decisions

From the Iron Gate viewing platform, on the exchange’s final day, the really big questions came into stark focus. Over the past two decades, as aging, fish-blocking dams come down across the American West, Mongolia is advancing the development of its own water infrastructure, including hydropower dams.

But as the Klamath dams illustrate, unforeseen and unintended consequences can accompany these river-altering infrastructure projects. In the Klamath, dam-building contributed to the near-extirpation of Klamath spring Chinook, a sharp drop in local fishing tourism, and water contamination from the reservoirs’ frequent toxic algal blooms. Dams can also create new anxieties; as they age, downriver communities must live with the increasing possibility of catastrophic dam failure.

As the Klamath dams illustrate, unforeseen and unintended consequences can accompany river-altering infrastructure projects.

Every development project has trade-offs, says Dr. Avlyush. She notes that time has brought improvements to hydropower, from more ecologically-informed project siting to better fish passage. And she hopes that Mongolian scientists and other experts can help expand the conversation to include the welfare of species like taimen, as well as Mongolia’s nascent ecotourism industry. There are also questions to consider about livestock, which can be sensitive to the water quality issues of some dams.

“In Mongolia, more than 90 percent of our rivers are free-flowing,” Dr. Avlyush says. “As scientists, part of our role is to take best practices from around the world and share them with decision-makers, including those who are planning to expand hydropower development in Mongolia.”

“In Mongolia, more than 90 percent of our rivers are free-flowing. As scientists, part of our role is to take best practices from around the world and share them with those who are planning to expand hydropower development.”

Wild Salmon Center Mongolia Senior Manager Dr. Saulyegul Avlyush

Local communities, she says, must also be part of these decisions. In Mongolia, taimen are revered by many. Across the Pacific, for Tribal communities including the Karuk, the century-long decline of salmon—and Chinook salmon in particular— has been devastating, bringing anxiety, health risks, and heartbreak.

For communities whose core identities center on wild fish and rivers, the impacts of long-ago decisions can last for generations. But that day on the Klamath, Toz Soto shared some exciting news. As the morning sun warmed the platform, members of the Mongolian delegation clustered around Soto to watch a stunning few seconds of video on his phone.

Sonar monitoring equipment had just caught images of a Chinook salmon swimming above the Iron Gate Dam site—possibly the first to do so in more than eight decades. (Soon after, salmon were confirmed migrating above all four dam sites, and even spawning in Oregon’s Spencer Creek.)

It was a breath of hope for this once mighty salmon river—one that, Soto shared, had felt like it might never come.

Sonar caught images of a Chinook salmon swimming above the Iron Gate Dam site—possibly the first to do so in more than eight decades.

So yes: common sense and science still hold that it’s better to protect a healthy salmon river than try to fix a broken one. But as one grainy video of a wriggling fish made clear that October morning, it’s not by chance that wild salmonids have survived for millions of years. Salmon can recover from some of the harshest things we can throw at them—if we give them a fighting chance.

“I think the message to folks that are coming from around the world to see this is that you as people that live on your river, you can protect it,” Soto says. “You can take ownership of your river and protect it. And if you have to, you can restore it.”

“The message to folks from around the world to see this is that you can take ownership of your river and protect it. And if you have to, you can restore it.”

Toz Soto, Karuk Fisheries Program Manager

Hero Image

Hero Image (Home Page Section)