To recover Olympic Peninsula steelhead, we need consensus on the science and history of the species’ decline. A new online approach offers Washington Coast steelheaders a chance to get it right.

Since the 1980s, Washington’s wild steelhead runs have been in sharp decline. On the Olympic Peninsula, the last five years have brought some of the lowest returns on record.

Up and down the Washington Coast, these numbers are alarming Tribes and guides, anglers and fisheries managers. Many fear a renewal of the emergency regulations that dramatically changed the Peninsula’s 2020 steelhead fishing season.

But recent declines are only part of the story, says Wild Salmon Center Science Director Dr. Matt Sloat. To really understand where we’re at with the state of steelhead, he says, we need to look further back in time.

“If our frame of reference only goes back a few decades, we miss the full picture of what these populations could look like,” Dr. Sloat says. “Even a couple generations ago, what people understood to be a healthy baseline for these wild fish was very different from today.”

LEARNING FROM HISTORY

When it comes to Washington’s revered, reclusive steelhead, expanding our frame of reference isn’t as simple as it sounds. One challenge is simply finding historical data to build that better baseline. As a result, state fisheries managers often make decisions (from escapement goals to emergency regulations) informed by contemporary fish counts. And that means we might be slow to recognize just how far these wild fish populations have declined.

That blind spot leads to another challenge we face in recovering steelhead: identifying proactive, rather than reactive actions. The emergency regulations of recent years might sound drastic, says Dr. Sloat, but these crisis measures, on their own, might not be enough to rebuild Peninsula steelhead populations. If managers, scientists, and others aren’t clear on what’s led to these declines over time, then our recovery actions will remain scattershot: reactions to what is right in front of us.

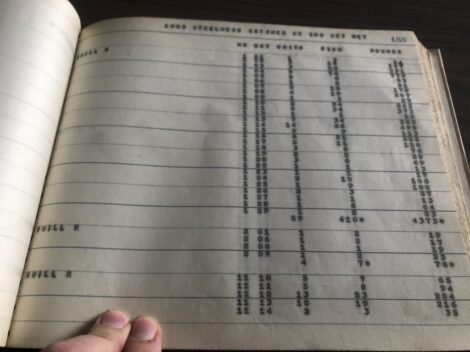

Luckily, even small, surprising discoveries can bring fresh light to the situation—like a single dusty, forgotten ledger in an Olympia office. Its carefully-typed daily fish counts start in 1948: decades earlier than the start of many steelhead population-tracking datasets. When combined with recent records, Dr. Sloat and a team co-led by Trout Unlimited’s John McMillan determined that just seventy years ago, Olympic Peninsula steelhead populations were more than double the size of today’s runs. This data also revealed another startling fact: steelhead are now returning 1-2 months later in the year.

“In the 1950s, between a quarter to one-half of Peninsula steelhead returned in November and December,” he says. “Now January is considered by many to be the start of the wild steelhead season.”

Just seventy years ago, Olympic Peninsula steelhead populations were more than double the size of today’s runs. Another startling fact: steelhead are now returning 1-2 months later in the year.

Could there be a connection between recent steelhead declines and shifts in run timing? Dr. Sloat would love to find out. He also knows the clock is ticking.

CENTERING SCIENCE

If Washington steelheaders are to unite around solutions, they’ll need answers to questions like those raised by scientists like Dr. Sloat. That’s why he and others are working hard to piece together historical steelhead runs and identify the key factors impacting steelhead declines.

“We have a good idea of the range of threats facing steelhead over the past century,” says Dr. Sloat. “What we need now is focused research to build consensus on which factors, in what combination, we should address first.”

Factors under investigation include whether earlier-returning steelhead favor different spawning habitat than later-returning steelhead—and whether the earlier run, as a result, has lost more of that habitat over the last 70 years to development like logging. Another set of questions concern hatcheries. According to Dr. Sloat, hatcheries might be impacting wild fish directly, through competition for resources—but possibly also indirectly. Hatchery steelhead are bred to return to freshwater at times that overlap with earlier-returning wild steelhead, creating prime conditions for increased accidental harvest by mixed-stock fisheries. If true, these scenarios could mean that what looks like a shift toward later run timing instead represents the gradual loss of earlier-returning steelhead.

If true, these scenarios could mean that what looks like a shift toward later run timing instead represents the gradual loss of earlier-returning steelhead.

Warming oceans, meanwhile, are likely also squeezing steelhead. WSC Board Director Dr. Nate Mantua, the leader of the Salmon Ecology Team at NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center, projects that by 2080, rising surface water temperatures in the ocean will shrink steelhead summer marine habitat by as much as 41 percent.

FORGING CONSENSUS

For Wild Salmon Center Washington Program Director Jess Helsley, the urgent need for answers has a silver lining: it’s driving a wide range of stakeholders to meet up and talk.

“The question we’re all asking ourselves right now is to fish or not to fish?” Helsley says. “It’s a heartbreaking situation, but it’s bringing everyone to the table.”

This new openness to collaboration is what has her feeling optimistic. That, and the early fruits of those conversations. In early September, WSC helped to convene an ambitious two-day steelhead science symposium with the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife and the Coast Salmon Partnership. More than 80 participants joined, including Washington Coast Tribes, federal agencies, and academics across several disciplines. Collectively, the participants began the work of identifying the critical data gaps currently impeding steelhead conservation science—work that will be further developed in a formal report. This report will help guide the Washington Coast Steelhead Information and Research Framework (SIRF), a new online data-sharing platform and action hub that will be hosted by WSC, CSP, and WDFW.

“I think pretty much everyone agrees that we need to find ways to prevent more emergency measures and rebuild these populations while also fishing,” says Dr. Sloat, who presented at the event. “But first we need to find ways to agree on how we got here. Hopefully SIRF is the foundation.”

Pretty much everyone agrees that we need to find ways to prevent more emergency measures and rebuild these populations while also fishing,” says Dr. Sloat. “But first we need to find ways to agree on how we got here.”

For steelhead scientists looking to answer those questions, the public resources centralized on the SIRF website will be critical, including a first-of-kind database of current and historical Washington steelhead data and an archive of scientific literature—including the new findings from Dr. Sloat and John McMillan’s team. Helsley says Washington Coast steelhead managers can also use SIRF to help address data gaps in expanded management criteria: criteria that goes beyond simple abundance to include productivity, distribution, genetic diversity, and climate change.

In challenging times, it’s human to want to react to what’s right in front of us, Helsley says. It can feel like there’s no time to take a breath, step back and assess. But when faced with the possibility of another year—or more—of emergency fishing regulations, Helsley says true hope lies in big-picture thinking.

“As tough as it may be to sit out this season and tie flies, it’s more important to make sure our children can fish,” she says. “Let’s take the time to truly set steelhead on a recovery path.”