Wellspring of a species: A steelhead origin story.

Part II, in the Heart of Steel story series | Part I | Part III

By Ramona DeNies

There’s a fish in Oregon’s Rogue River, no bigger than your forearm. It’s bright silver with a rounded jaw, big-eyed and dappled with black spots.

In fish years, it’s barely a teenager—a “half-pounder,” so-called for reasons you can guess. And like all salmonids of the species Oncorhynchus mykiss, this one has a secret life.

Our half-pounder has been here for months, hanging out with younger, smaller rainbow trout that haven’t yet seen the ocean—and may not ever. Some battle-hardened adults are also here: large, pink-cheeked, returned from years at sea. They’re not eating, just holding: waiting for their moment to spawn.

Among the young smolts and wizened elders, the half-pounder is something else.

Technically, it’s a steelhead—because it did take the ocean plunge that triggers a rainbow trout’s amazing transformation. Its gills and kidneys can now process saltwater. It has tasted squid and shrimp. But after three to five months, the half-pounder came back, as if for a gap year.

“I think steelhead might be the most complex of all salmonids,” says Wild Salmon Center Polsky Research Fellow Dr. Tasha Thompson, a genetic scientist who lives one large watershed north of the Rogue. “The sheer diversity of decisions that steelhead make on an individual level—it shows us how little we still know about their inner life, what drives them.”

Historically, steelhead claimed rivers from Baja California, north to Alaska and across to Western Kamchatka. Across that range, their life path varies dramatically—in years spent in freshwater and at sea, in whether they spawn once, twice, or even four times.

“The sheer diversity of decisions that steelhead make on an individual level—it shows us how little we still know about their inner life, what drives them.”

Wild Salmon Center Polsky Research Fellow Dr. Tasha Thompson

But half-pounders are commonly found in just three rivers in North America: the Rogue, Klamath, and Eel, all in or near the Klamath-Siskiyou, a steep mountain region straddling the Oregon/California border. Data suggests that smaller smolts tend to be the ones who dip back early to freshwater. Maybe those ocean months were rough. Maybe our half-pounder hoped to be the big fish on campus. Right now, it isn’t revealing its secrets.

What we do know is that on the Rogue, Klamath, and Eel, half-pounders are a good example of the next-level biodiversity found in these steelhead rivers. That, in fact, could be the real story.

“For humans, we see the greatest genetic diversity in Africa, where our species has its origins,” Dr. Thompson says. “The genetic hotspot for steelhead is California, in the southern part of their range today. That’s why it’s thought that this area is their ancestral home.”

“The genetic hotspot for steelhead is California. That’s why it’s thought that this area is their ancestral home.”

WSC Polsky Research Fellow Dr. Tasha Thompson

Half-pounders don’t exist in the Umpqua Basin, where Dr. Thompson lives. Here, wild summer steelhead are the big attraction, pooling in cold springs and tributaries, casually eluding hopeful anglers.

Dr. Thompson spends long days tracking these fish on the North Umpqua. But usually, nights are better.

WSC Polsky Research Fellow Dr. Tasha Thompson and her partner, Dr. Mike Miller, on the banks of the North Umpqua River. (Video still from The Lost Salmon courtesy Jason Hartwick, Swiftwater Films.)

“At night, they’re kind of sleepy, and come out onto the gravel,” she says. ”I’ll sit there in the dark, with a headlamp, in a little pool of light. It’s a whole different world. I’ll hear all these sounds. There are crawdads and salamanders. I’ve been growled at—by what, I’m not sure.”

In the world of salmon conservation, Dr. Thompson is among a select group of leading scientists (a surprising number here, between the North Umpqua and Eel) that also take it to the next level.

In 2017, she was part of a team that discovered the specific gene responsible for run timing in both steelhead and Chinook salmon: a finding that’s now informing persuasive new arguments for federal protections. Then, in 2018, her groundbreaking research revealed that the loss of one key gene factored into the fast decline of spring Chinook in Oregon’s Upper Rogue River.

“We know that the reason why salmon and steelhead have been so successful is their ability to adapt,” Dr. Thompson says. “They have a portfolio of strategies honed over millions of years.”

Steelhead, in particular, can pivot on a dime: darting out to sea or not at all, extending their ocean adventures by years, straying to new spawning grounds or even entirely different rivers. Female steelhead can spawn with a fierce, fanged-out 30-pound buck, or with a freshwater rainbow trout not much older than our half-pounder.

“They’re smart, and very curious,” Dr. Thompson says. “And they’re powerful, like a Formula One race car. You can watch them swim up to a 10-foot waterfall, raise their head, and take a test jump. And if it doesn’t work, they try something else.”

Such powerhouse moves go way back. As a species, steelhead bank on a wealth of behavioral and physiological options honed and cached since at least the Miocene Era, 10 million years ago.

“Steelhead are powerful, like a Formula One race car. You can watch them swim up to a 10-foot waterfall, raise their head, and take a test jump. And if it doesn’t work, they try something else.”

WSC Polsky Research Fellow Dr. Tasha Thompson

If one approach doesn’t cut it, steelhead find a different line. If a barrier in a river proves insurmountable, that run might evolve to return when it is passable. If a young smolt meets rough seas, it can head back to freshwater early, and try its luck.

The problem? In many steelhead rivers, human interference and climate change are now drawing down these genetic reserves faster than steelhead can adapt. Historically, West Coast fisheries managers just haven’t had the kind of reliable long-term data that clearly illuminates a trend. But in recent years, new research from Wild Salmon Center scientists and others shows that steelhead are declining fast—and have been for decades.

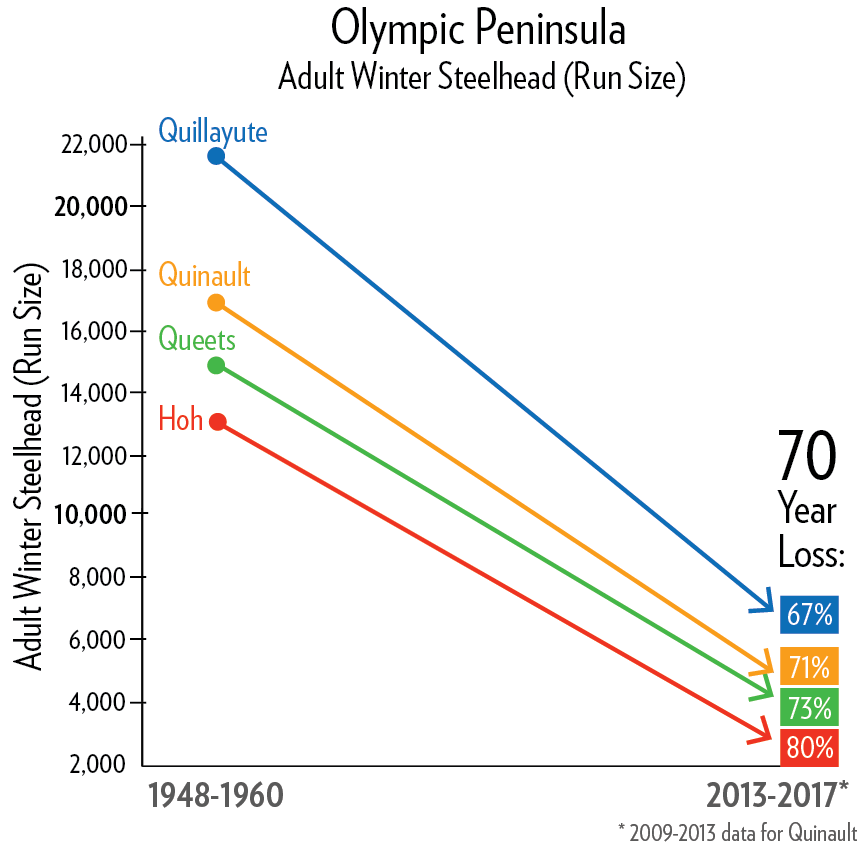

In British Columbia, new data on vulnerable steelhead stocks is fueling a campaign to ban marine fish farms and reform mixed-stock fisheries. In the Olympic Peninsula, steelhead are now at a fraction of their historical abundance. Further south, from the Columbia River to Southern California, many steelhead runs are listed as endangered. And where recreational steelhead fisheries still exist, closures are now alarmingly routine.

“We’ve known for a while that steelhead are in trouble,” Dr. Thompson says. “But it’s only recently that we’re learning what makes them tick—and how to use that information to drive policy and restoration work.”

To really understand the story of steelhead, Dr. Thompson says, we need to go back to the beginning.

“We’ve known for a while that steelhead are in trouble. But it’s only recently that we’re learning what makes them tick.”

WSC Polsky Research Fellow Dr. Tasha Thompson

The Eel River, in Northern California, is steep and redwood-shaded, a study in turquoise and chert. Over millennia, ice and water carved its upper reaches into a wonderland of steep canyons and boulders as large as houses.

Today, the Eel River basin is dry and hot. Summers can be blistering: not where you’d guess that coldwater O. mykiss would thrive. But as we’ve mentioned, steelhead are adaptable.

“We know that steelhead successfully made use of these particular circumstances for millions of years,” says Samantha Kannry, an Arcata-based fisheries biologist with the Native Fish Society. “It’s thought that in precolonial times, you could have seen maybe a million salmon and steelhead in the Eel.”

Kannry has lived here in Humboldt County for the past 14 years. She’s an expert on Eel River steelhead. And it’s true—she lives to swim with the fishes.

“We know that steelhead successfully made use of these particular circumstances for millions of years.”

Samantha Kannry, fisheries biologist with the Native Fish Society

“In a deep, crystal-clear cold pool on a hot day, you’ll get used to seeing juvenile trout,” she says. “But then you see these giant adults, jumping a little bit, but mostly just hunkering down and waiting.”

This is a trick that all salmonids learn, young and old: to nose out a river’s coldest water and hold there till it’s time to hopscotch higher, or flow down toward the ocean.

For millennia, a combination of spring snowmelt and complex geography have made the Eel particularly hospitable for steelhead. Winter steelhead show up as early as late fall—spawning within weeks and often returning to the ocean. Summer steelhead, arriving with the spring rains, traditionally climb higher into the Eel’s upper reaches and cold pools, waiting out hot summer months before spawning.

The Eel’s long hospitality also owes something to the fens near the Van Duzen River, an Eel tributary only accessible to summer steelhead.

Fens are ancient sponges, mires of waterlogged organic material that often connect with other waterways through underground seeps. In the case of the Van Duzen, they’ve likely provided the river with reliable cold water pockets for millennia. How long, Kannry can’t say for sure—fens can take tens of thousands of years to form. But she does know that a small crew of humans can chop one up and haul it away in days.

Fens are mostly sphagnum, or peat moss: perhaps the world’s most coveted potting soil. For less-than-ethical marijuana growers in Humboldt County, the lure of this black gold has proven irresistible.

“We think that more than 90 percent of the fens on the north side of the mountain have been illegally mined,” Kannry says. “So in a relatively short period of time, we’ve made what was an evolutionarily advantageous place somewhere that’s now very hard for steelhead to live.”

These days, steelhead—summer in particular—are struggling throughout the Eel. The river’s once-heavy spring snowmelt is now disappearing. The Van Duzen’s unique summer run is near extirpation.

According to Kannry, the reasons for this decline are legion, from the loss of the fens to heavy logging, cattle grazing, road building, and other human interventions. The dams aren’t helping, either; for more than a century, the Scott and Cape Horn dams have cut off hundreds of miles of potential steelhead spawning habitat.

“In a relatively short period of time, we’ve made what was an evolutionarily advantageous place somewhere that’s now very hard for steelhead to live.”

Samantha Kannry, fisheries biologist with the Native Fish Society

It bothers her, the huge and often unacknowledged costs of human self-interest. Kannry wishes more people saw this fish the way she does: an ancient mariner of sagas, an athlete that can leap up churning cascades, a superhero that can control its own metabolism, sometimes fasting for many months before spawning.

But there are still reasons to hope that this region can remain a wellspring for the species. With a 2021 state move to list Northern California summer steelhead as endangered, more funding is now available for habitat restoration, fish passage improvements, and preservation of key landscapes like the fens. There’s also growing momentum across the West to remove problematic dams: aging structures that often need costly repairs, provide diminishing value to human communities, or—the case of the Eel’s dams—both.

Another reason to hope is the growing scientific community backing the kind of research and data that fisheries managers so urgently need.

Dr. Thompson, Kannry’s former lab partner at the University of California at Davis, is currently working on an ambitious genomic map spanning the entire range of steelhead. No resource like it yet exists. When released to the public, it could be a game-changer for understanding—and recovering—the species.

“Tasha once told me how much she loves studying genetics and seeing the science support what Tribes and First Nations have known for a long time,” Kannry says. “Steelhead are amazing. They literally bring life to the rock. What’s most important to me is getting that across to people.”

Consider, she says: we have no idea what life path our half-pounder will take: when and why it will again head to sea, where it will journey. What it will see. All we really know, Kannry says, is that journey’s end will be one of the world’s most beautiful places.

Wouldn’t you want to be in on that secret?

“Steelhead literally bring life to the rock. What’s most important to me is getting that across to people.”

Samantha Kannry, fisheries biologist with the Native Fish Society