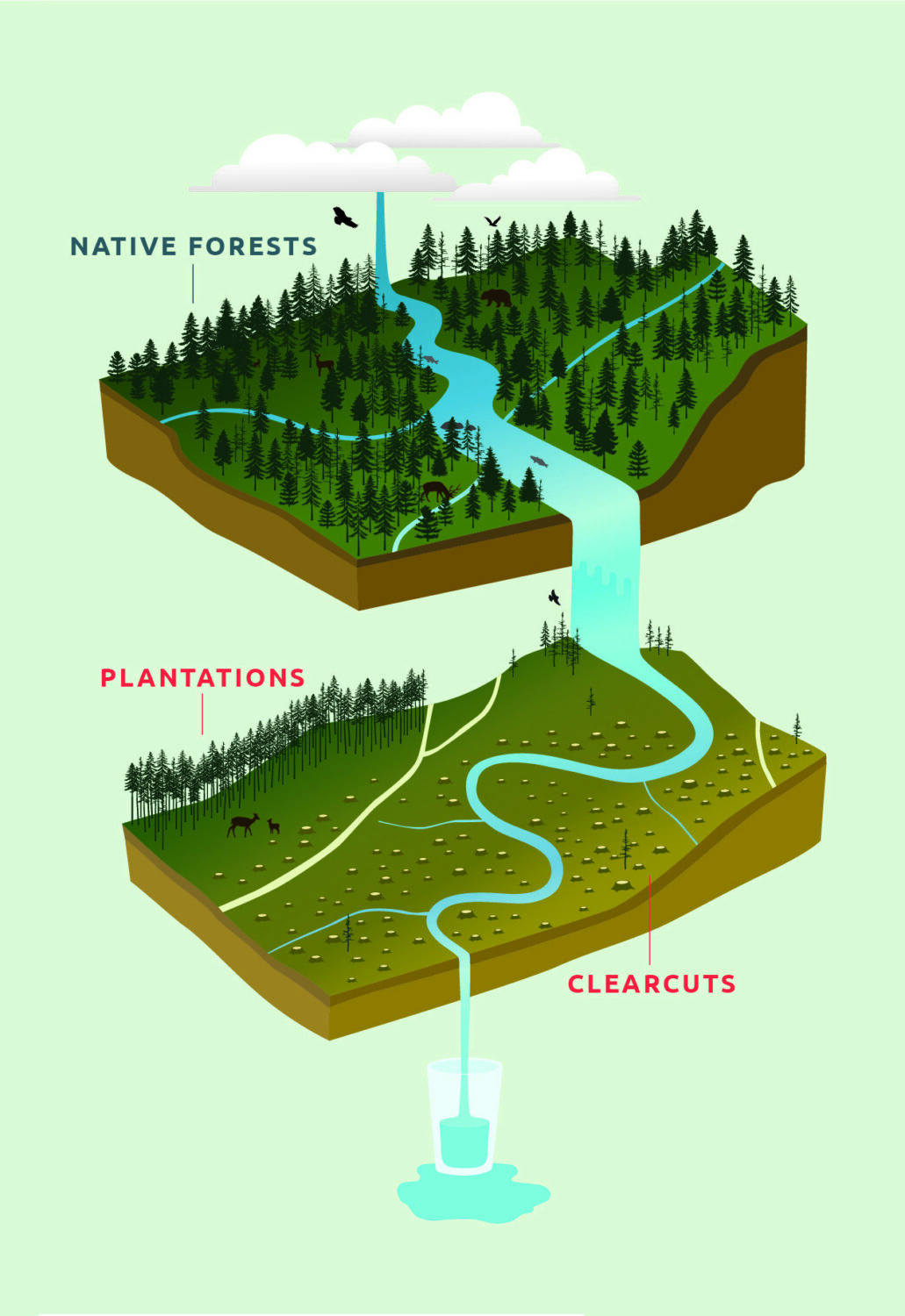

Wilder rivers and warmer water: a new study shows that industrial forestry makes life harder for wild fish across the West.

Across Western North America, clearcuts scar coastal forests. In many communities, questions linger about the impacts of industrial logging on salmon. After all, competing messages about forestry and forest health have churned for more than a century.

Now, a comprehensive new study finds that though impacts can vary widely by watershed, logging at any level can carry significant risks for salmon rivers.

Published in Ecological Solutions and Evidence, the study synthesizes more than 50 years of water temperature and streamflow data from watersheds ranging from California to Alaska.

And the results are telling—starting with the finding that in summer, stream flows in logged watersheds can be up to 50 percent lower than those without logging impacts.

To examine the question of how logging impacts salmon rivers, the research team—including scientists from Simon Fraser University’s Salmon Watersheds Lab and Wild Salmon Center—drew data from a previously unsynthesized trove of “paired catchment” studies that compare logged watersheds with similar, unlogged systems.

“We asked, ‘what datasets out there could possibly give us insights about forestry across a broad swath of salmon country?,’” says Dr. Matt Sloat, WSC’s Science Director and a study co-author. “Paired catchment studies were the answer.”

For decades, explains lead author and former SFU researcher Dr. Sean Naman, this model of study has captured forestry impacts in individual salmon watersheds. Each paired catchment study monitors stream temperature and flow conditions in two watersheds: one with logging impacts, and one without. Over time, a critical mass of paired catchment studies accrued in scientific journals—potential pieces of a larger story.

“Paired catchment study results vary from watershed to watershed,” Dr. Naman says. “But since the general approach is very similar, we merged these data to see what new insights we could learn.”

The team synthesized an initial dataset of more than three dozen paired catchment studies and found that a few clear takeaways emerged despite the high variability of the individual studies.

Broadly speaking, watersheds with logging impacts had peak flows that were higher than unlogged systems by a mean 20 percent. But summer stream flows were also a mean 25 percent lower (and as much as 50 percent lower) in the logged watersheds, and hotter by a mean 15 percent.

Overall, the data suggests that forestry does make life harder for Pacific salmon: driving rivers to be wilder and more volatile in rainy, high flow seasons, and hotter and drier in summer.

Warmer temperatures and lower stream flows are generally bad news for salmon—both as juveniles gathering strength for their ocean journey and as adults returning to home rivers. Furthermore, forestry impacts on freshwater may exacerbate climate change-related shifts towards warmer and lower flows that are already affecting salmon.

Dr. Naman’s team hopes the study’s findings can support more nuanced dialogue among land-use planners: dialogue that allows more space for weighing the potential risks and unintended outcomes of industrial forestry.

“People may want a clear-cut line to say what level of forestry is too much,” Dr. Naman says. “But given the variability within the studies, we found no simple and generalizable threshold. With this uncertainty, we advise planners without more detailed information for a given watershed to proceed with caution.”

“People may want a clear-cut line to say what level of forestry is too much. But given the variability within the studies, we advise planners to proceed with caution.”

Lead author Dr. Sean Naman, formerly of Simon Fraser University’s Salmon Watersheds Lab

For his part, Dr. Sloat hopes that the study’s findings help ensure that salmon remain central to the evolving conversation around forestry. Wild salmon, he says, are a keystone species—critical to forest and community health across the Pacific Rim.

“We already know that salmon face unprecedented threats from climate change,” Dr. Sloat says. “In an era of rapid climate change, it’s more critical than ever to understand how forestry also warms salmon streams and changes their flows. This study deepens our understanding.”

“We already know that salmon face unprecedented threats from climate change. it’s more critical than ever to understand how forestry also warms salmon streams and changes their flows.”

Study co-author and Wild Salmon Center Science Director Dr. Matt Sloat

Comprehensive studies like this, he says, have a role to play in advancing the next generation of land use policies. They provide a foundation of fact that can cut through competing messages—and unite decision makers around the understanding that forestry at any level does bring some risk for salmon.

From this shared foundation, says Dr. Sloat, we can plan better futures for wild fish in watersheds across the coastal West.