How we’re getting ready for change in salmon strongholds.

Climate change is a daunting global problem that is upending life as we know it. But we at Wild Salmon Center believe we can and must make an impact through local and regional action, to make sure salmon survive this century and to help local communities feeling the worst effects of climate change. Tribal communities face the continued loss of key food sources and their cultural identity. Fishing, hunting, and recreation-based communities face job losses, food scarcity and a strained social fabric.

Focusing on protecting and restoring both watersheds and the wild fish diversity between and within fish populations gives salmon and salmon-based communities a fighting chance in the face of so much change. And resilience-focused local habitat and fisheries actions also fit into larger national and international strategies to deal with excess atmospheric carbon and worsening ocean conditions.

WSC developed a resilience framework to drive local action in salmon strongholds.

DIG DEEPER >> Read WSC’s Resilience FrameworkHere’s a summary of how we’re framing climate change and the work we all need to get done to prepare fish and watersheds for change.

Updating the Stronghold Approach

The heart of WSC’s mission is the ‘stronghold approach,’ a conservation strategy designed to protect the core centers of wild salmon abundance and diversity around the Pacific Rim.

Now it is critical that we now look at strongholds through the lens of climate resilience.

How will existing salmon strongholds hold up under a new level of climate pressure? What characteristics of the watersheds and fish populations must be protected, restored, and reinforced to make sure strong wild populations don’t just persist, but thrive? How can our actions on individual stronghold rivers contribute to the global fight to stop climate change?

Maintaining watershed function and healthy wild salmon runs in strongholds, as well as empowering local conservation champions, is essential in the face of climate change.

These resilient strongholds anchor our fight to conserve wild Pacific salmon range wide.

Understanding Local Resilience Risks and Opportunities

A key part of our resilience strategy is understanding local risks and opportunities.

Climate change planning in salmon conservation often starts and ends with a discussion of the anticipated exposure of watersheds and fish populations to changing climatic conditions. WSC considers two additional criteria – sensitivity to anticipated changes and adaptability of resident and anadromous fish populations – when evaluating the resilience of species and watersheds.

LEARN MORE >> Read the Framework

Turning to Action

With a deeper local understanding of how watersheds can remain resilient in the face of climate change and how fish populations’ natural adaptability can be bolstered, we can turn to action. And science suggests that intact, functioning ecosystems have the greatest resilience to change.

Proactive conservation is the best way to protect intact natural processes in relatively unaltered places such as Bristol Bay, Alaska and Kamchatka in the Russian Far East.

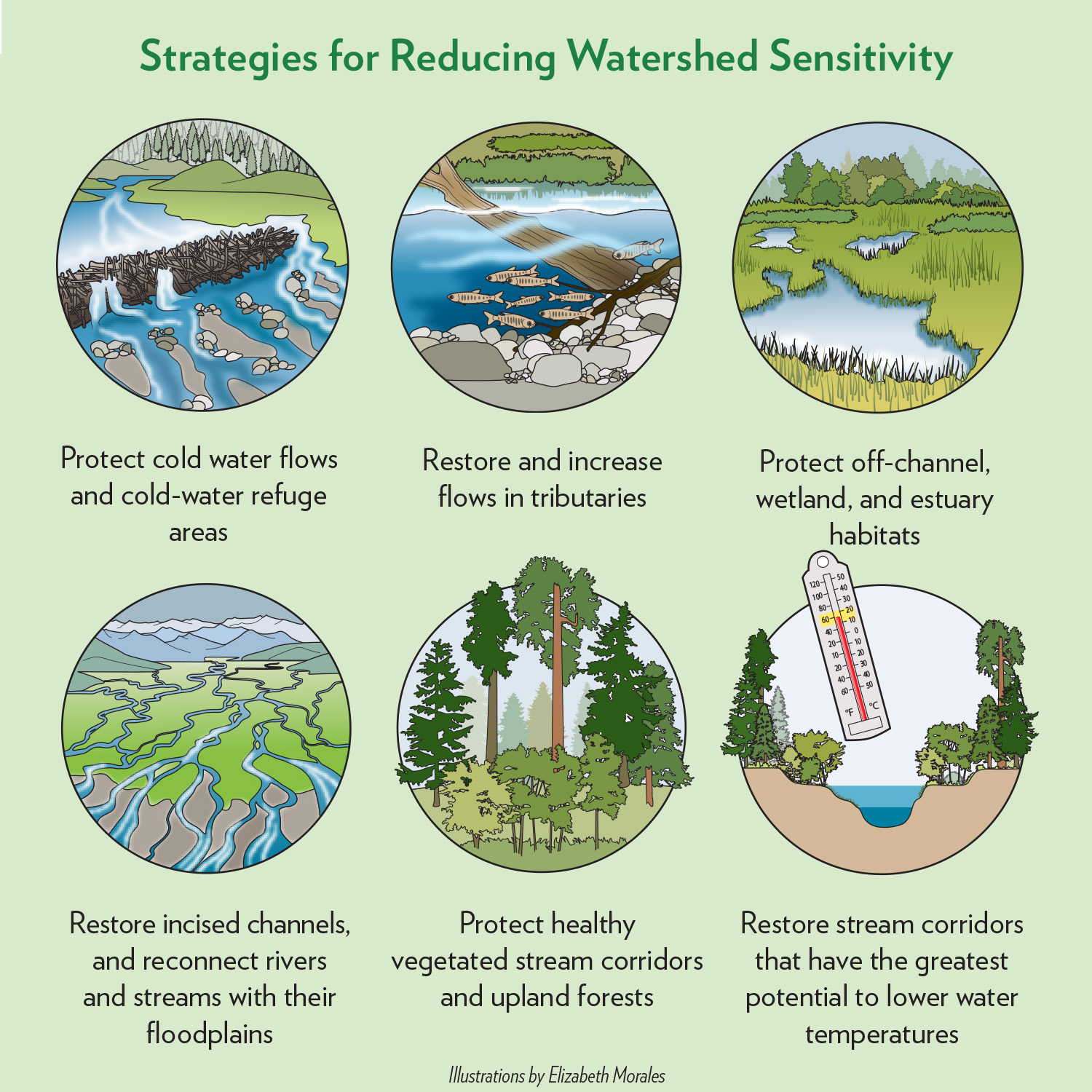

Where watersheds have been disturbed, we need to take strategic restoration steps – not all restoration builds resilience. Key restoration actions include protecting cold water flows and cold-water refuge areas, restoring access to wetlands, estuaries and off-channel habitats, and conserving streamside forests.

Ensuring salmon and steelhead populations can adapt to climate change means maintaining healthy, abundant populations, and protecting and restoring their genetic and life history diversity. That includes escaping enough fish with enough genetic and life history diversity to sustain and rebuild wild salmon abundance; transitioning ocean fisheries that catch mixed runs of fish to terminal and selective fisheries – to avoid overharvest of small populations and endangered stocks; and stopping the expansion and negative impacts of fish hatcheries.

DIG DEEPER >> Read WSC’s Resilience Framework

Slowing Climate Change: Why Strongholds Are Key

Focusing on protecting and restoring critical salmon population and ecosystem functions also mitigates climate change by sequestering carbon.

Land management is a key front in mitigating climate change. A 2018 study led by the Nature Conservancy estimated that improvements in land management could absorb up to a fifth of the United States’ annual emissions – the equivalent to taking all cars and trucks off the road.

Restoring and protecting salmon habitat in coastal wetlands and mature temperate rainforests is an important carbon sequestration strategy. Coastal temperate rainforests in Oregon and Washington have been identified as some of the most important in the Lower 48 for mitigating climate change. These forests, including the Tillamook Rainforest and the rainforests on Olympic Peninsula, are also home to some of the last, best salmon and steelhead runs south of Canada. Similarly, the Great Bear Rainforest of British Columbia and the Tongass and Chugach National Forests of Southeast Alaska harbor substantial reserves of old-growth forest and host salmon strongholds such as the Copper, the Stikine and the Skeena rivers.

Alaska’s Bristol Bay region, home to world’s largest run of sockeye salmon, is also a massive tract of largely undeveloped wetlands and peatlands the size of Wisconsin. As a coalition of Alaska Native communities, tourism and fishing businesses defend the region from hard rock mining proposals, they are also keeping intact a massive carbon sink.

In the Russian Far East province of Khabarovsk, Wild Salmon Center and Russian partners are working to protect several hundred thousand acres of boreal peatlands – home to salmon and the endangered mega-trout, Siberian taimen. Although they cover just three-percent of the world’s land surface, peatlands are the most effective land type for storing carbon.

Building salmon resilience at the local and regional level has significant climate change benefits for the world. And it will be an essential part of the American and international drive for net-zero emissions.

The Way Forward

We believe that greater watershed and species resilience can be accomplished, but it requires a shared understanding and commitment across the salmon conservation and management spectrum, from those in the field to those in state capitols.

The faster that conservation practitioners adopt a resilience approach, the sooner we will begin to see the benefits, in communities and ecosystems.

LEARN MORE >> Read the Framework