A comprehensive analysis published in Bioscience finds that traditional salmon fishing practices and governance show promise for rebuilding resilient fisheries.

Across the North Pacific, salmon fisheries are struggling with climate variability, declining fish populations, and a lack of sustainable fishing opportunities. According to a study published today in BioScience from a team of Indigenous leaders and conservation scientists, help lies in revitalizing Indigenous fishing practices and learning from Indigenous systems of salmon management.

“Salmon and the communities that depend on them have been pushed to the brink by two centuries of extractive natural resource management,” says lead author Dr. Will Atlas, Salmon Watershed Scientist with the Portland-based Wild Salmon Center. “But the tools, practices, and governance systems of Indigenous peoples maintained healthy salmon runs for millennia before that. Their knowledge is still here.”

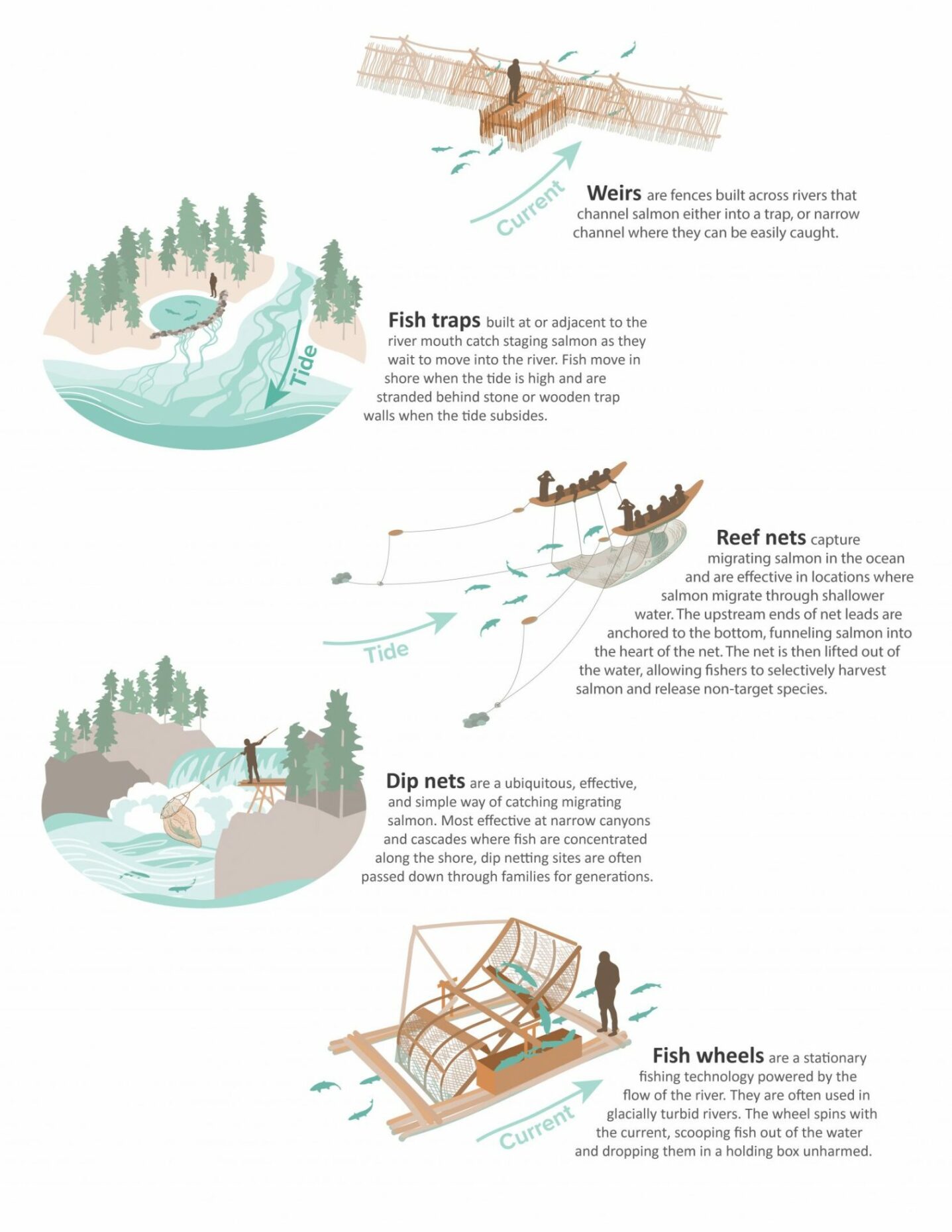

The paper documents how, for thousands of years, Indigenous communities around the North Pacific maintained sustainable salmon harvests by using in-river and selective fishing tools like weirs, traps, wheels, reef nets and dip nets. Following European contact, these traditional fisheries and governance systems were suppressed, and often outlawed outright, as commercial fishing interests came to dominate fisheries.

“As they’re currently built, mixed-stock salmon fisheries are undermining the biodiversity needed for Pacific salmon to thrive,” says Dr. Atlas. “Luckily, we have hundreds of examples, going back thousands of years, of better ways to fish. These techniques can deliver better results for all communities.”

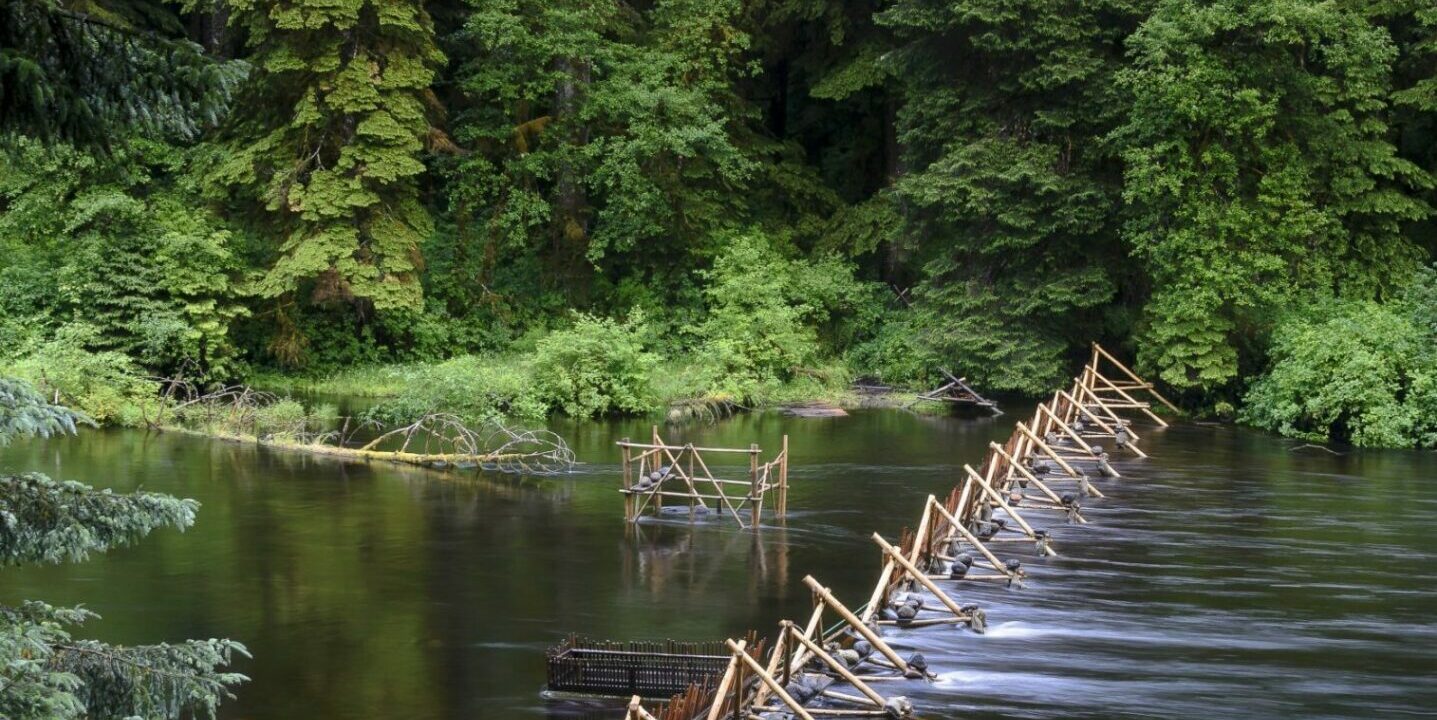

A key example explored in the study is Indigenous peoples’ focus on terminal fisheries. By targeting salmon runs in river systems—rather than in the ocean, where more vulnerable and healthy stocks intermingle—Indigenous people harvest individual, known salmon runs. Selective fishing tools, like the Heiltsuk Nation’s traditional-style fish weir in the Koeye River in British Columbia, also enable in-season monitoring, where fishers can assess a run’s health in real time, while releasing non-target species unharmed.

“In my Nation, we use fish wheels, an ancient technology that used to be made out of cedar and natural fibers,” says co-author Andrea Reid, a citizen of the Nisga’a Nation and an assistant professor in Indigenous Fisheries at the University of British Columbia’s Institute for Oceans and Fisheries. “Today, we use modernized fish wheels to monitor, mark, and study the fish, to understand how they are doing in a rapidly changing world.”

Indigenous salmon management knowledge stems from more than respect for a primary food source. For many communities, salmon are at the center of creation stories, ceremonies, family structures, and cultural identity.

“The ancient relationship between Heiltsuk and salmon infiltrates every aspect of Heiltsuk life,” says co-author William Housty, a member of the Heiltsuk Nation and Board Chair with the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department in Bella Bella, British Columbia. “Our modern-day management of salmon is based on the values of respect, reciprocity, and wellbeing.”

As colonization severed access to traditional fisheries, Tribes and First Nations have experienced complex, ongoing harms. Restoring Indigenous co-governance to salmon management is a crucial part of the reconciliation process. According to the study’s authors, restoring Indigenous governance can also help decentralize salmon management decisions at a time when diverse climate impacts are challenging watersheds like never before and demanding local responses.

“In an era of rapid global change, we must explore different salmon management approaches,” says co-author Dr. Jonathan Moore, a professor in Biological Sciences at British Columbia’s Simon Fraser University. “By reinvigorating Indigenous practices, we can bring time-tested lessons to salmon fisheries and take a positive step toward recognizing the cultural fabric that has woven salmon and humans together for millennia.”

There’s still hope for these fisheries, the authors say, if managers embrace Indigenous communities’ focus on terminal fisheries and selective fishing tools, strengthen Indigenous co-governance, and decentralize salmon management decisions with climate resiliency in mind.

Indeed, many of the lessons of Indigenous fisheries are already being applied in commercial fisheries such as Bristol Bay, Alaska, where, the authors note, “networks of locally interconnected terminal fisheries have alleviated conservation risks and produced stable harvest opportunities.”