In the ailing timber towns of the Olympic Peninsula, long-term conservation work creates jobs and helps communities rebuild.

When Mike Nelson’s family first came to the Washington Coast, the massive shipbuilding mobilization of the World Wars had given way to a thriving timber industry. For a full century, Nelson’s relatives made their living right here, working the lush forests of the Olympic Peninsula.

“I think every person in the timber industry sees it as a legacy,” says Nelson, who followed in his stepfather’s footsteps by launching his own forestry contracting company, Olympic Resources, about five years ago. “It’s the American dream, is how I look at it.”

“Every person in the timber industry sees it as a legacy,” says Nelson.

For those two earlier generations, the ancient, dense coastal forests felt like an inexhaustible resource, supporting shake mills and whole towns, providing logging jobs for anyone ready to learn the business. But for Nelson’s generation, things are different. The Pacific Northwest’s endless canopy is now patchy with clear cuts. Regulatory pressure and Big Timber have squeezed local economies, complicated further by efforts to conserve water quality, wildlife habitat, and iconic species like wild salmon.

“I see the environmental aspect of it. Fish are important to everybody,” Nelson says. “But like any small community that’s survived off timber dollars, mine has been hit pretty hard. The opportunities out here are few and far between.”

“Like any small community that’s survived off timber dollars, mine has been hit pretty hard,” says Nelson. “The opportunities out here are few and far between.”

Nelson lives near Lake Quinault in a tiny town called Amanda Park. In recent decades, “big city problems” have come here: substance abuse and homelessness, the handmaidens of high unemployment. But Nelson, a hunter and fisher and father of five, has no plans to leave. He thinks this place has a future. He traces the same resilient spirit that flexed from shipbuilding to timber forward to a new line of work that can lift his community: stream restoration.

“It’s the new way, not the old way. Maybe you can’t just go through there and lay a creek any more,” Nelson says, referring to the streamside clearcutting practices of times past. “But as long as you want to learn, there’s work.”

A NEW LINE OF FORESTRY WORK

In the last decade, Nelson has channeled his heavy equipment operation and logging skills into building a new line of work. Restoration projects—site-specific and often aimed at protecting drinking water streams and enhancing fish and wildlife habitat—now make up an increasing part of his paycheck.

“Some years, forty or fifty percent of my work is stream restoration,” says Nelson. “There are a lot of pipes out there that need replacing.”

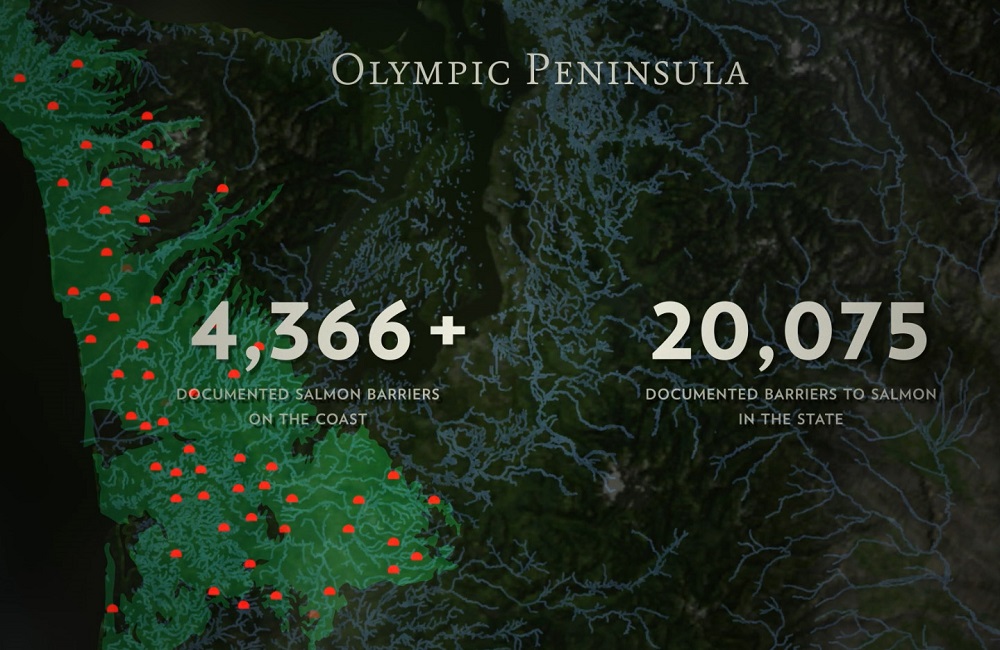

In summer, Nelson and his crew go full bore on replacing those pipes—aging and failing culverts that block fish passage. Hundreds of these fish barriers dot streams across the Washington Coast, says Betsy Krier, Wild Salmon Center’s Forks-based Fish Habitat Specialist and a frequent project manager on barrier removal alongside partners at Trout Unlimited, Clallam Conservation District, Pacific Coast Salmon Coalition and the Quileute Tribe.

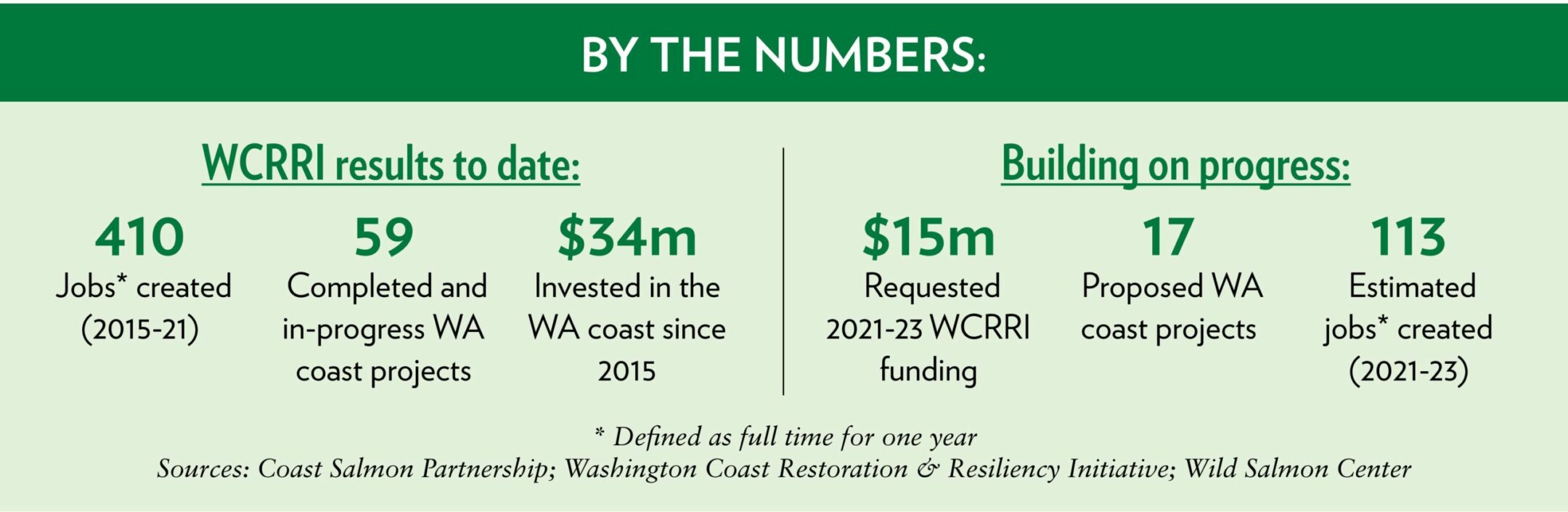

From 2015 through this year, a myriad of project sponsors have managed 59 restoration and culvert replacement projects on the Washington coast, creating 410 full-time, one-year jobs in the process. That’s thanks to state funding through the Washington Coast Restoration and Resiliency Initiative, the Salmon Recovery Funding Board and the Brian Abbott Fish Barrier Removal Board.

In a way, Krier says, restoration work brings the coastal economy full circle, repairing the heavy impacts of timber booms past.

“The culverts are here because we built lots of roads to extract timber,” says Krier. “And at the time, fish passage wasn’t necessarily on people’s minds.”

What’s also ironic, for Nelson, are the weird flashbacks. In the 1950s, when his stepfather launched his company, Clearwater Resources, there was work to be had in “cleaning” streams of woody debris. Now, Nelson and some of his fellow contractors earn money putting trees back into those streams.

In the 1980s, there was work to be had in “cleaning” streams of woody debris. Now, Nelson and some of his fellow contractors earn money putting trees back into those streams.

“Used to be, it was okay to pull trees out,” says Nelson. “Obviously, fish like shade and trees. But they did it differently—that’s what they knew. Lake Quinault, they used to dredge it. When you talk about dredging now, it’s like, ‘oh Lord.’”

This past summer, Nelson and his crew worked with Krier and Trout Unlimited to excavate a undersized culvert that had bottlenecked Ziegler Creek, a Lake Quinault tributary, since the 1960s.

“Mike comes in there with this massive equipment, and his job is to make these finely engineered renderings come to life,” says Krier. “It takes someone at Mike’s level of competence to make these really detailed projects happen. It’s the kind of competence you get when you have not just experience, but also an openness to trying new things.”

In Ziegler Creek, Nelson’s professional precision is already paying off. This November, Krier received an excited phone call from a nearby resident. He’d been walking just upstream of the former culvert when he saw splashing and looked closer.

There they were: two Chinook salmon spawning in the now free-flowing creek.

WORK THAT BUILDS A BETTER FUTURE

To Nelson, stream restoration is work that feels good. Long-term, it also feels practical: work he can count on well into the future. According to Krier, he’s right about that.

“There’s a lot of work to get done on the Washington Coast,” says Krier. “The work that we’re doing with the Cold Water Connection campaign, we’re looking at five, ten, fifteen year-increments. And we’re relying on people like Mike to help us get it done.”

Right now, she and her restoration partners are gearing up for their next round of state-funded projects—17 total, stretching from the Columbia River to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The Coast Salmon Partnership estimates the 2021-23 project slate will create some 113 full-time jobs, most of them local. According to one report, 80 percent of every dollar invested in local restoration projects stays in-county, and 90 percent stays in-state.

“A lot of people don’t know that there are opportunities like this out there,” says Nelson. “Given a chance, a lot of these contractors can come in and get it done. These guys are in the thick of it already.”

From culvert removal and road decommissioning to carefully engineering logjams in streams, Krier says restoration work needs skilled professionals like Nelson to be successful.

And it’s work that will benefit families like Nelson’s for generations to come—in cold, clean drinking water, revived fisheries, and healthier, wildfire-resistant forests—even as it helps put food on the table today.

“There has to be a reason for why we’re doing what we’re doing,” Nelson says. “Knowing I was a part of it, looking forward to the future, I wonder what all this is going to look like in 25 years.”

Restoration work will benefit families like Nelson’s for generations to come—in cold, clean drinking water, revived fisheries, and healthier, wildfire-resistant forests—even as it helps put food on the table today.

Hero Image