On the Washington Coast, our Cold Water Connection Campaign is building a turnkey database of high-priority salmon restoration projects. It’s already unlocking government funding.

At milepost 0.51 on rural Oil City Road, a yellow arrow points traffic around a dip over Two Trout Creek. The bypass is the result of a road washout in the late 1990s—a fact of life here, on Washington’s rainy Olympic Peninsula.

At the time, Jefferson County’s fix for the road was supposed to be temporary: two culverts under the bypass to help stabilize the creek as it tumbled to meet the Hoh River, just a few miles from the Pacific Ocean.

Fast forward twenty years, and those culverts are still there: twin spigots that drop the creek four vertical feet over sharp riprap. In the creek below this temporary firehose, coho salmon, steelhead, and resident trout trying to swim upstream now confront a new and impassable barrier.

“The culverts alleviated that particular road washout problem,” says Wild Salmon Center Fish Habitat Specialist Betsy Krier, a resident of nearby Forks. “But they also created a fish problem.”

According to Jefferson County Transportation Planner Wendy Clark-Getzin, her team wanted a permanent fix—a bridge to straighten the road out again. But funding is tight on the Olympic Peninsula, and the county has a long waiting list of infrastructure issues competing for attention, like along the scenic Upper Hoh Road, a tourism thoroughfare for the Olympic National Park rainforest.

Breaking bottlenecks like these—physical, financial, ecological—is a key part of WSC’s Cold Water Connection Campaign work with the Coast Salmon Partnership and Trout Unlimited. Our team has spent the past several years bushwhacking and snorkeling across the Washington Coast to identify the most important fish passage projects from a list that runs into the thousands. We’re even recruiting private funding to kickstart design for these top projects. And with our partners, we’ve merged all this information—including data culled from multiple landowners and state and local jurisdictions—into a single, searchable database that maps the benefits of hundreds of fish passage corrections.

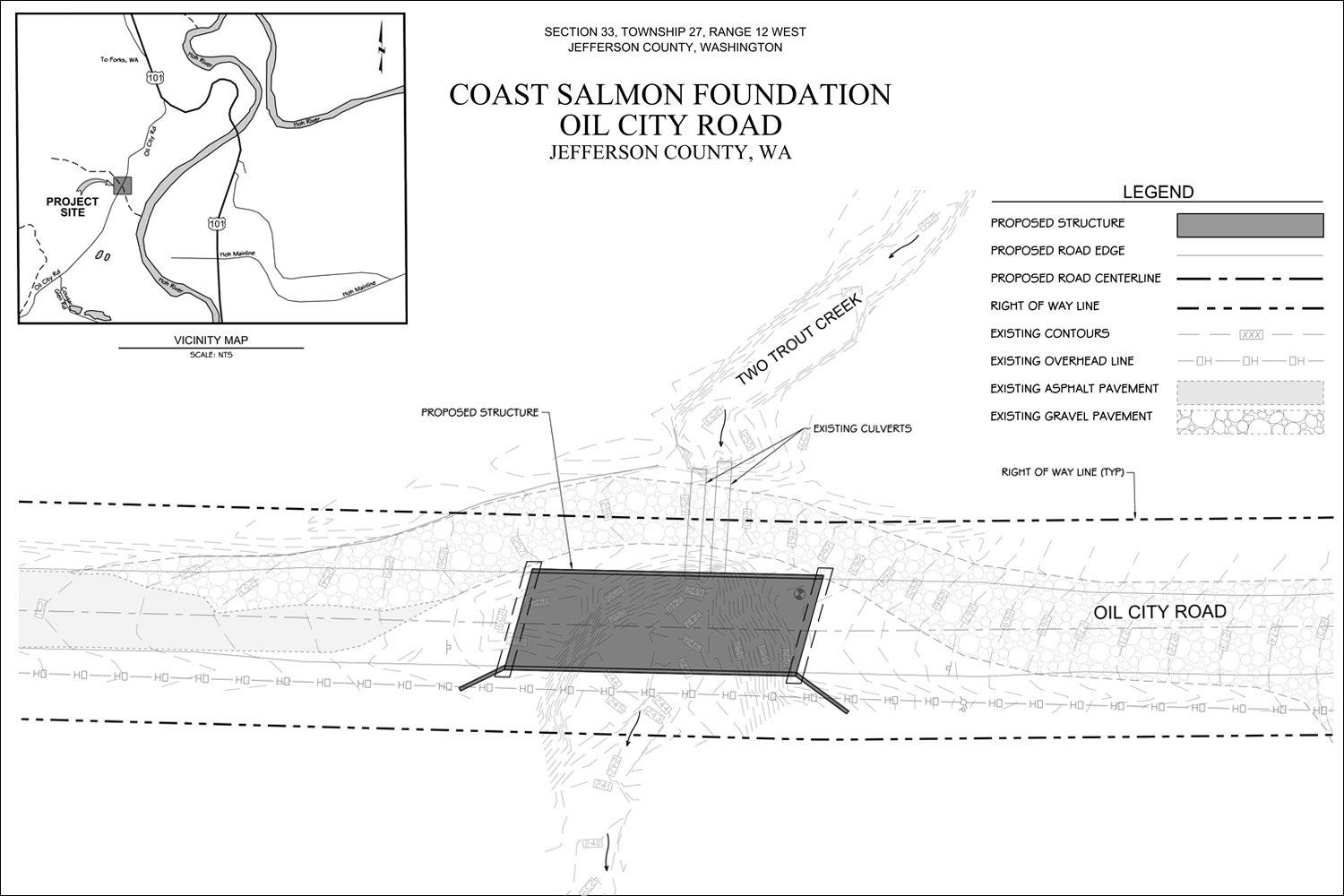

Now, the Cold Water Connection Campaign is starting to net serious funding for local governments. In 2020, Jefferson County Public Works submitted the campaign’s preliminary design for fixing Oil City Road to the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Lands Access Program (FLAP).

“We’d already penciled it in from a roads programmatic perspective,” says Clark-Getzin. “Then Coast Salmon Partnership put a spotlight on it, and made the case that it was worthy of dealing with now. It was a win-win.”

Breaking bottlenecks—physical, financial, ecological—is a key part of WSC’s Cold Water Connection Campaign work.

Federal grant administrators agreed. In spring 2021, FLAP awarded Jefferson County $1.8 million to replace these Oil City Road culverts with a long-span bridge, a conceptual design that comes right out of our prioritization database, made possible by funding from Cold Water Connection Campaign private donors including the Wallace Research Foundation. Another private donor, the Resources Legacy Fund, is supporting five additional preliminary designs this year via a grant made through the Open Rivers Fund, an RLF program supported by The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

Clark-Getzin confirms that our team’s advance design work on Oil City Road saved Jefferson County time and money. But it also provided another advantage: outside validation of this project’s importance. To identify the highest-priority projects, WSC and our partners rank each fish passage barrier by a complex ecological score that weighs granular criteria (e.g., how many river miles a correction would reopen) alongside broader benefits such as a watershed’s potential climate resiliency.

“We wanted this first partnered project to be a big success,” Clark-Getzin says. “Oil City Road had all the elements: tourism, habitat, transportation. The work we did with the Coast Salmon Partnership kick-started this project by years. A FLAP-funded project is basically a turnkey operation.”

Work on the project is still a few years out, she says, as the FLAP funding won’t be officially allocated until 2024. But Clark-Getzin and her team, energized by this bottleneck-breaking momentum, are already working on their next culvert removal project on Oil City Road.

According to Mara Zimmerman, Executive Director of the Coast Salmon Partnership, this is exactly the kind of public-private collaboration that the campaign’s partners are looking to fast-track, by helping to give administrators like Clark-Getzin a running start.

“We built this tool for just this purpose: to accelerate smart salmon recovery funding for the Washington Coast at a critical time for our wild fish,” says Zimmerman. “Oil City Road is the first project to bear fruit, but it won’t be the last.”

More than 4,300 known salmon barriers dot the Washington Coast, a potentially paralyzing number for anyone wondering where to pitch a shovel. But motivated planners like Clark-Getzin are finding fresh support for these local infrastructure projects from national political leaders. Washington Senator Cantwell and Representative Kilmer are both currently sponsoring Congressional infrastructure bill amendments that would create a national culvert correction program, in recognition of the benefits to drinking water, wild fish, and rural communities that flow from these investments.

“Culverts might feel out-of-sight, out-of-mind, especially when tearing down big dams is also on the table,” says Krier. “But if we truly want to recover our wild fish and our fishing way of life, these are the projects that help juvenile and returning salmon reach the cold water they need to ride out hot summers.”

In Jefferson County, Clark-Getzin and her team are just getting started with the partnership. They’ll be using the Cold Water Connection Campaign database to help drive pipeline of future culvert correction projects.

“We’re hoping that this goodwill spreads out to additional partnerships with the Hoh Tribe and others,” says Clark-Getzin. “There are a lot of projects ahead of us.”

Culverts might feel out-of-sight, out-of-mind,” says Krier. “But if we truly want to recover our wild fish and our fishing way of life, these are the projects that help juvenile and returning salmon reach the cold water they need to ride out hot summers.”

Hero Image