A WSC-coathored study reveals concerning trends—and lessons—for Washington’s prized wild steelhead runs.

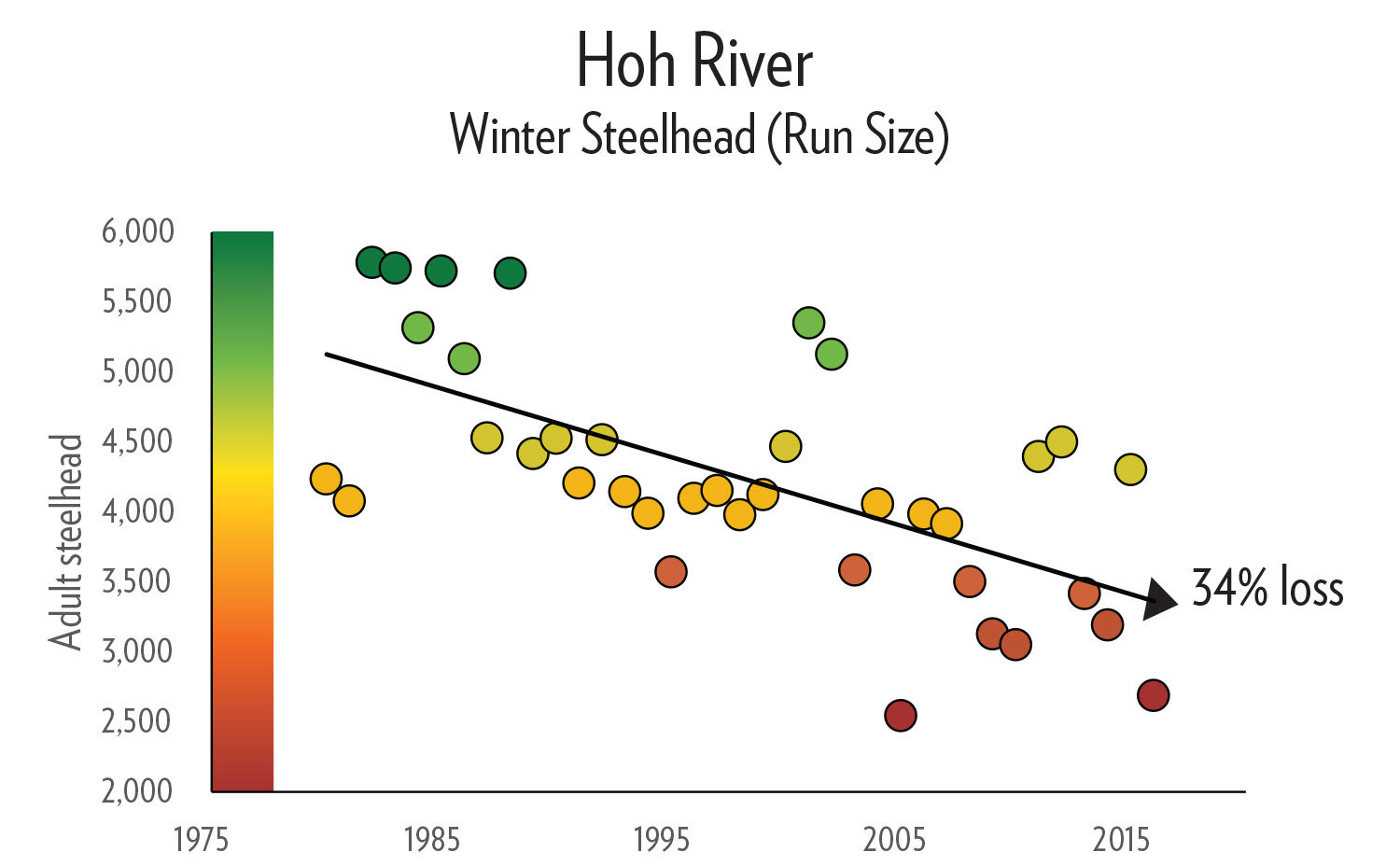

Wild steelhead populations in the Olympic Peninsula have declined by more than half since the 1950s.

This alarming fact is one of the main findings of a new paper published in the North American Journal of Fisheries Management from Wild Salmon Center Science Director Matt Sloat, Trout Unlimited’s John McMillan, and Martin Liermann and George Pess from NOAA’S Northwest Fisheries Science Center.

In the study, the authors confirm another uncomfortable trend shaping reality for steelhead fishers and fishery managers: the OP’s wild steelhead are returning to freshwater an average one to two months later than they did 70 years ago.

“In the 1950s, between a quarter to nearly one-half of Peninsula steelhead returned in November and December,” Dr. Sloat says. “Now January is considered by many to be the start of the wild steelhead return season.”

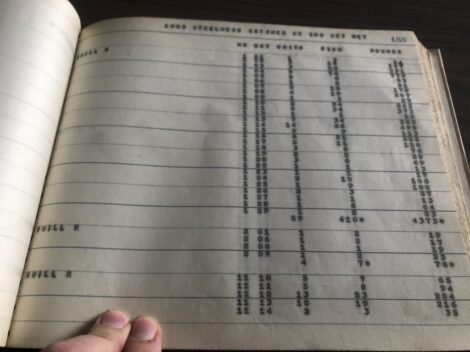

The evidence suggests that steelhead aren’t simply pushing back their return season. Aided by newly-discovered troves of historical data, the study’s authors determined that steelhead runs have largely lost their early returners, truncating the run. This loss is likely connected to declining abundance, notes Sloat.

Steelhead aren’t simply pushing back their return season. Aided by new troves of historical data, the study’s authors determined that steelhead runs have largely lost their early returners.

“Run timing influences the opportunity for fish to access different habitats within a watershed,” he says. “The loss of earlier returning fish means that the remaining population has fewer options for using the available habitat. As a result, overall steelhead production suffers.”

When it comes to steelhead, historical insights like these have been hard to come by. That’s because management agencies often lack the long-term data needed to see the big picture. As a result, fisheries managers must often rely on contemporary fish counts to make decisions on everything from goals for fish reaching spawning grounds (known as escapement) to emergency regulations. And that narrow lens means we might be slow to recognize just how far these wild fish populations have declined.

Luckily, research from conservation scientists including Sloat and McMillan is expanding the historical data set available to agencies like the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife. Just one of the team’s discoveries—a single dusty ledger in an Olympia office—helped to backfill daily fish count records to 1948: decades before many steelhead population-tracking datasets even start.

When combined with recent records, the study’s authors determined that just seventy years ago, Olympic Peninsula steelhead populations were more than double the size of today’s runs.

“Extending the dataset is important because it provides a longer-term context,” says McMillan. “For example, until recently, wild steelhead on the OP were considered to be healthy and relatively robust compared to many other regions. We now know not only are many contemporary populations in decline, but that the OP supported far more steelhead than we previously thought.”

So why, exactly, is steelhead run timing changing? And why are steelhead numbers dropping? It’s complicated. Factors that the paper investigates include whether earlier-returning steelhead favor different spawning habitat than later-returning steelhead—and whether the earlier run, as a result, has lost more of that habitat over the last 70 years to land use practices like logging. Another set of questions concern hatcheries.

“There has been a long-held assumption that selecting hatchery steelhead for early entry in December would reduce impacts on wild fish,” says McMillan. “That doesn’t appear to be the case on the OP. The historical catch data indicates wild steelhead were fairly common in November and abundant in December and January, so there was an extensive amount of overlap in run timing between hatchery and wild fish prior to the onset of the modern hatchery steelhead programs.”

“There has been a long-held assumption that selecting hatchery steelhead for early entry in December would reduce impacts on wild fish,” says McMillan. “That doesn’t appear to be the case on the OP.”

According to the paper, hatcheries might be impacting wild fish directly, through competition for resources—but possibly also indirectly. Since hatchery steelhead are bred to return to freshwater at times that overlap with earlier-returning wild steelhead, that might create conditions for increased accidental harvest of earlier-returning wild fish by mixed-stock fisheries. If true, this could mean that the gradual loss of earlier-returning wild steelhead is, at least in part, a result of overharvest.

These questions can make for complicated conversations among diverse stakeholders, Sloat admits. But everyone agrees that steelhead are in trouble. Last year, as steelhead numbers up and down the Washington coast entered their fourth straight year of rapid decline, WDFW enacted emergency rule changes on many coastal rivers.

Yet annual emergency rule changes don’t make for a sustainable management strategy, notes Sloat. For WDFW to build a more effective plan of action—one that can enable long term population health for steelhead—the agency will need strategies to restore steelhead diversity, including run timing, that underpinned the strong runs of the past.

In November, WDFW took a major step in that direction, creating a community advisory panel to develop new, watershed-specific management plans for the state’s steelhead populations. According to Sloat and McMillan, these plans will have the greatest chance for success if they incorporate targets for improving wild steelhead diversity and resilience, in addition to abundance.

“We have a history in fisheries management of focusing almost exclusively on the numbers of fish,” says Sloat. “It’s time we implemented a broader view of fishery management—one that considers steelhead productivity, distribution, and diversity alongside total abundance. And we applaud OP fishery managers for their recent incorporation of these additional criteria into their management efforts.”

The broader management perspective can’t come soon enough for OP steelhead, he says.

“We need all hands on deck to set coastal steelhead on a recovery path,” says Sloat. “Rebuilding won’t be easy, but our study provides a glimpse of what recovery could look like: diverse and abundant wild Peninsula steelhead runs. We look forward to collaborating with our partners on this work in the years ahead.”

“We need all hands on deck to set coastal steelhead on a recovery path,” says Sloat. “Our study provides a glimpse of what recovery could look like: diverse and abundant wild Peninsula steelhead runs.”