With First Nations fisheries managers and other key partners, WSC launches “Salmon Vision”—a first-of-its kind machine learning model to track salmon returns in real-time.

Right now, in rivers across British Columbia’s Central Coast, we don’t know how many salmon are actually returning. At least, not until fishing seasons are over.

And yet, fisheries managers still have to make decisions. They have to make forecasts, modeled on data from the past. They have to set harvest targets for commercial and recreational fisheries. And increasingly, they have to make the call on emergency closures, when things start looking grim.

“On the north and central coast of BC, we’ve seen really wildly variable returns of salmon over the last decade,” says Dr. Will Atlas, Wild Salmon Center Senior Watershed Scientist. “With accelerating climate change, every year is unprecedented now. Yet from a fisheries management perspective, we’re still going into most seasons assuming that this year will look like the past.”

One answer, Dr. Atlas says, is “Salmon Vision.” Results from this first-of-its-kind technology—developed by WSC in partnership with the Pacific Salmon Foundation, Gitanyow Fisheries Authority, and Skeena Fisheries Commission—were recently published in Frontiers in Marine Science.

“With accelerating climate change, every year is unprecedented now. Yet from a fisheries management perspective, we’re still going into most seasons assuming that this year will look like the past.”

WSC Senior Watershed Scientist Dr. Will Atlas

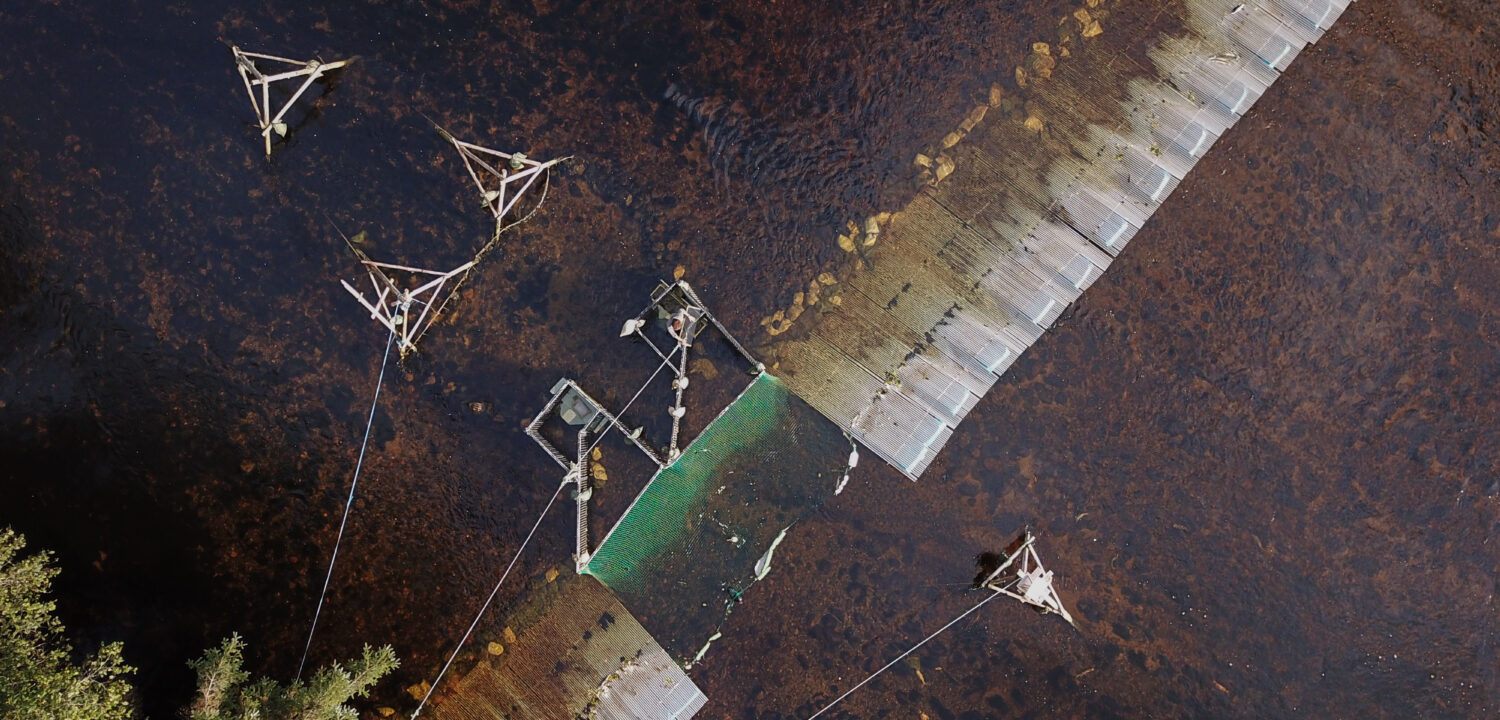

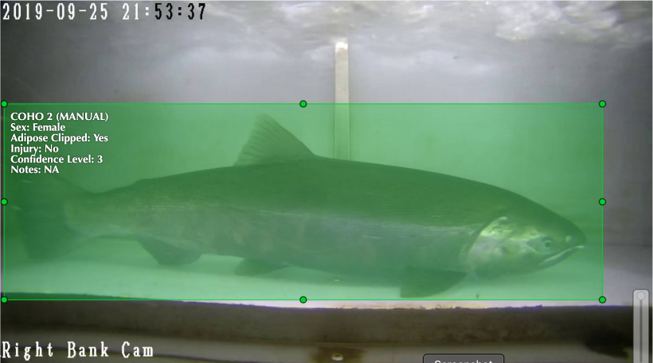

Combining artificial intelligence with ancient fishing weir technology, the Salmon Vision computer deep learning model leverages rapidly emerging artificial intelligence tools to identify and count fish species.

The goal is to enable real-time salmon population monitoring for First Nations fisheries managers and beyond.

“Many of our First Nations partners are telling us that we need to automate fish counting to make informed decisions while salmon are still running,” Dr. Atlas says. “And underwater video technology can now help us literally see those salmon return to rivers.”

“We need to automate fish counting to make informed decisions while salmon are still running. And underwater video technology can now help us literally see those salmon return to rivers. ”

WSC Senior Watershed Scientist Dr. Will Atlas

The Salmon Vision pilot study annotates more than 500,000 video frames captured at Indigenous-run fish counting weirs on the Kitwanga and Bear Rivers of B.C.’s Central Coast. Early assessments show promising adeptness in tracking 12 different fish species passing through custom fish-counting boxes at the two weirs, with scores surpassing 90 and 80 percent accuracy for coho and sockeye salmon: two of the principal fish species targeted by First Nations, commercial, and recreational fishers.

Salmon Vision is also running on a weir operated by the Heiltsuk Nation on the Koeye River.

For First Nations like the Heiltsuk, weirs represent more than a revitalization of an age-old fishing technology. Banned in the late 1800s by Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans as a way to consolidate control of fishery resources, the rebuilding of weirs on rivers like the Koeye is a statement both of First Nations sovereignty and their seat at the table in fisheries management decisions.

“The Koeye weir is a modern-day expression of not only Heiltsuk title and rights, but also an avenue for us to be a part of the latest science,” says William Housty, Associate Director of the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department. “And to make decisions not just for the betterment of this creek, but for the whole ecosystem.”

Now, the Salmon Vision team is implementing automated counting on a trial basis in several rivers around the B.C. North and Central Coasts with partner First Nations, with a goal of providing reliable real-time fish count data to these partners by 2024. Ultimately, Dr. Atlas says, this groundbreaking A.I. technology could be in place in rivers across the North Pacific.

“We need information on how many salmon are returning everywhere that we’re fishing for salmon,” Dr. Atlas says. “You can’t tell me with a straight face that you’re having a sustainable fishery if you don’t know how many fish you have coming back. And that’s a problem right around the Pacific Rim.”

It’s a problem with a promising solution—one that’s just now coming into focus.

“You can’t tell me with a straight face that you’re having a sustainable fishery if you don’t know how many fish you have coming back. And that’s a problem right around the Pacific Rim.”

WSC Senior Watershed Scientist Dr. Will Atlas