A Wild Salmon Center Science Advisor on how salmon can find their path in a changing world.

Glaciers are melting. Sea levels are rising. Just two more ways that climate change spells catastrophe for salmon—right?

Across the North Pacific, there’s no doubt that wild fish are struggling. But according to Dr. Jonathan Moore, a Wild Salmon Center Science Advisor and the Director of Simon Fraser University’s Salmon Watersheds Lab, we can still make a huge difference in how well some runs adapt to our changing world.

“The story of climate change is one of massive transformation, but also of agency,” Dr. Moore says. “The actions we take today will have a huge impact on the ability of salmon to adapt in the future.”

Case in point: rising sea levels. The same conditions that will elevate flood risk for communities will also inundate the estuaries that provide critical rearing habitats for young salmon.

But since we know these changes are coming, Dr. Moore says, we can be proactive—fixing or removing fish-blocking dikes and culverts, for example, and reconnecting estuary floodplains so they can continue to support salmon and fisheries into the future. Proactive planning can also benefit salmon and people in glacially-fed watersheds, Dr. Moore says—as with the Taku River Tlingit First Nation, which is exploring ways to safeguard future salmon habitat within its territory from extractive industries.

“We often hear about how the salmon journey is one of cumulative harms from humans,” says Dr. Moore. “But we can flip that narrative. Because it’s also possible for humans to provide cumulative benefits to salmon across their life cycle.”

Below, we talk with Dr. Moore about the way forward for salmon in a changing climate, and the beauty of straying from the beaten path.

“The story of climate change is one of massive transformation, but also of agency. The actions we take today will have a huge impact on the ability of salmon to adapt in the future.”

Dr. Jonathan Moore, Simon Fraser University

A Conversation With Dr. Jonathan Moore

Wild Salmon Center: You’ve co-authored studies that look at how sea level rise, glacier retreat, logging, and mining could impact salmon well into the future. Why focus on the future?

Dr. Jonathan Moore: My early work focused on how salmon changed ecosystems—how amazing abundances of salmon can engineer landscapes and support so many other species. But over time, my work has gotten more and more focused on applied questions of how ecosystems are changing. And what we can do about it.

Climate change is unfurling across the salmon life cycle. It used to be a topic of, ‘oh, it seems like this might be happening.’ But the data is now rolling in on the impacts of oceans and estuaries warming, food webs shifting, stream flow changing. The loss of snowpack and ice. And the human impacts that keep chipping away at salmon habitat.

The reality is that we’re asking too much of salmon and their ecosystems. There are so many ways where we can take action and lessen harms to salmon. And, because the world is changing so fast, we need to know what’s going to be important for salmon in the future.

WSC: Salmon conservation often centers on protecting and restoring habitat right now. Is it doable to expand this work to habitat that hasn’t even been created yet?

Dr. Moore: It feels quite doable. The path forward aligns to some extent with what people are already doing. We just need to be a bit more holistic about how we think about salmon habitat. For example, large-scale dam removals like the Elwha River continue to showcase the ability of salmon to flourish if given the chance.

We don’t always know precisely how salmon ecosystems are going to change. This uncertainty just means that there is even more of a need to protect large functional ecosystems and their different habitats. This approach, like the Wild Salmon Center stronghold approach, keeps in play more of the potential puzzle pieces of habitat that salmon might need in the future.

“The path forward aligns to some extent with what people are already doing. We just need to be a bit more holistic about how we think about salmon habitat.”

Dr. Jonathan Moore, Simon Fraser University

In some cases, however, the science is actually pretty clear on what we can expect. For example, we estimated that glacier retreat will open more than 6,000 new kilometers of salmon rivers by about 2100, largely in the transboundary region and southeast and central Alaska. These new river miles mean new local opportunities for salmon to find habitat and flourish. But these future habitats are also at risk from mining companies that are already staking claims in these emerging ecosystems.

WSC: What specific actions can we take now to protect the salmon habitat of the future?

Dr. Moore: One example that inspires me is the Gitanyow First Nation in the Nass Basin. They’ve experienced glacier retreat, and have seen salmon moving into these recently deeply glaciated regions. So they’ve expanded their Protected Area to steward future generations of salmon and fight back against mining companies.

WSC: Let’s say we take the example of the Gitanyow and attempt to protect areas that we think might be great future salmon habitat. How do we know that salmon will even find it?

Dr. Moore: Remember that salmon evolved and adapted over millions of years in landscapes and watersheds that were always changing. Salmon are renowned for finding their way back home. But they’re also great at finding new habitats. Usually, a small percent of a run strays so they return to somewhere other than their home spawning grounds. Scientists think that straying is an evolutionary strategy—so that salmon don’t literally put all their eggs in one basket.

This combination of homing and straying is really powerful. Homing means that over time salmon can fine-tune their life histories and biology through local adaptation. And straying means that salmon can also find new landscapes. They can tap into those future promises.

WSC: So as glaciers melt, we can act now to protect potential emerging salmon streams from extractive industries and development. What other opportunities do you see?

Dr. Moore: One project I’m really excited about is called the Estuary Resilience Project, led by the Nature Trust of British Columbia and many coastal First Nations. The project’s collaborative research and monitoring looks at how estuaries will rise with sea change—to inform and catalyze large-scale, forward-looking estuary restoration projects.

The urgent concern is “coastal squeeze”—where coastal habitats like marshes and estuaries will be squeezed between coastal development and a rising ocean. Estuaries are critical habitats for young salmon. Young salmon can grow fast in estuaries—growth that bolsters their future survival in the ocean. In one intact estuary, we discovered that estuary growth and residence can boost ocean survival for coho salmon by more than 40 percent.

Because we have a sense of what’s coming, there are real opportunities for us to help these habitats remain productive for salmon even with coastal squeeze. For example, we can pursue the large-scale removal of dikes and culverts to restore the natural connectivity of estuaries as sea levels rise. We can make smart decisions now to build resilience—for salmon, for fisheries, and for coastal communities.

“We can make smart decisions now to build resilience—for salmon, for fisheries, and for coastal communities.”

Dr. Jonathan Moore, Simon Fraser University

WSC: With so much at stake—and so many factors that could still shape the future of salmon in unknowable ways—how do you stay motivated in your research? What keeps you going?

Dr. Moore: Well, I feel so fortunate to work in these watersheds. The people I work with are amazing. From scientists to Indigenous Guardians, there’s something very special about spending a long day with a small team of folks, with rain and mosquitoes and bears, wading through rivers. I love listening to the people and places where I get a chance to work. It’s deeply inspiring. And the fish themselves are amazing.

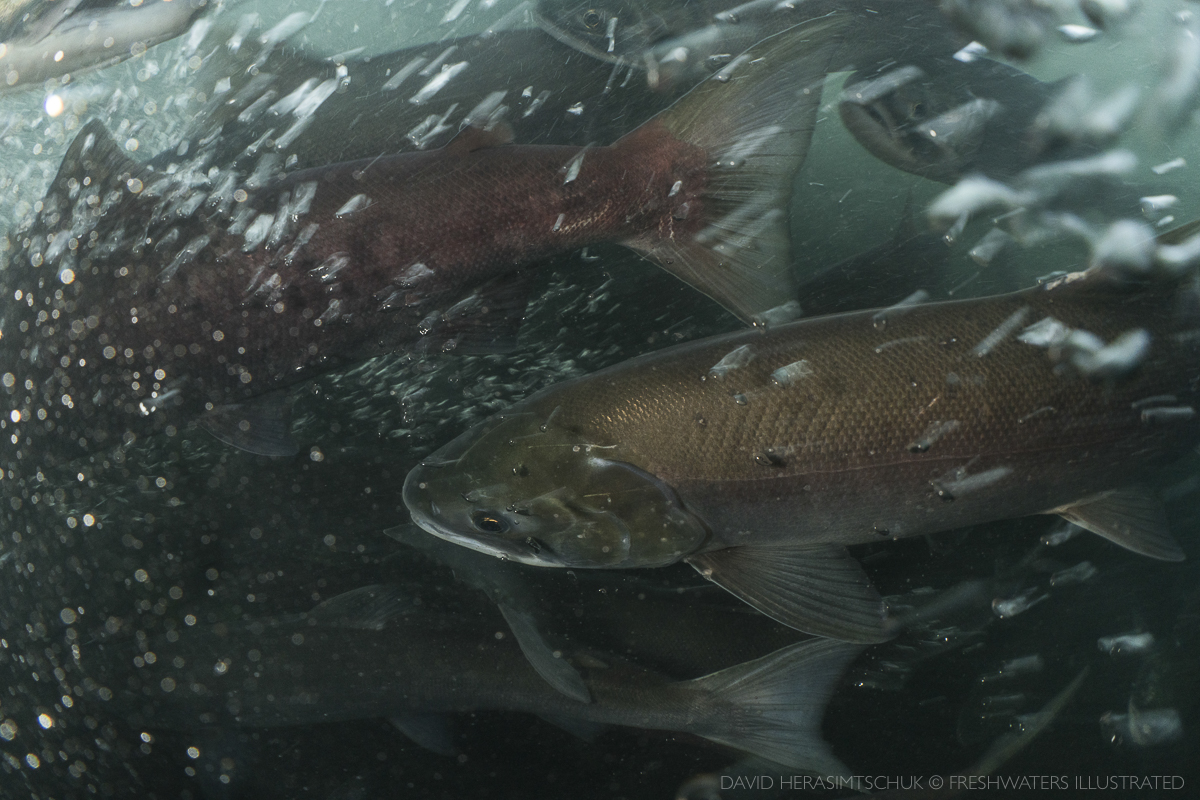

One moment that really stuck with me: I was in the Nass watershed at the base of a waterfall. I got into the river in a drysuit and a mask, and found I was surrounded by dancing salmon. I struggled to not get swept downstream and was holding hard onto a boulder, but the fish looked effortless. It was beautiful clear water, and the bubbles looked like shining diamonds. It made me think about how this moment was part of something so much bigger: a migration that started with these fish traveling out to sea, and then returning back again. Swimming up these cascades and this water that melted from ice fields hundreds of kilometers upstream. Everything was so big and so connected. It was hard to wrap my mind around.

After that, I sat on the banks and watched these fish try to make the leap up the falls. I think I counted 500 before I saw one make it up. And they just kept trying.

Learn more here about Wild Salmon Center’s Science Advisory Board.

“I watched these fish try to make the leap up the falls. I think I counted 500 before I saw one make it up. And they just kept trying.”

Dr. Jonathan Moore, Simon Fraser University