Orcas and Actions

In the Salish Sea, declining spring Chinook runs mean Southern Resident orcas go hungry. It’s a simple supply-and-demand problem. But to fix it, humans must take actions as complex as any food web.

Part IV, in the First Salmon, Last Chance story series

By Ramona DeNies

A baby orca rolls and breaches in the Salish Sea. It’s 2019, and she’s still wobbly, just a few months old, but her mother has to leave her and go hunting.

So little Tofino, or J56 as she’s known to orca scientists, is being watched by her extended family. Drone footage from the Center for Whale Research captures their play: a fin slap against the surface, a couple lazy crescents, a collective dive, side-by-side, with three young orcas lined up by size.

Baby Tofino watched by older family members in 2019. Watch mama Tsuchi enter the frame at 0:48, followed by a flash of white at the minute mark as Tsuchi shares a salmon bite. (Video clip courtesy Center for Whale Research and University of Exeter. Full video here.)

Video also captures the moment her mother Tsuchi (J31) returns. Tofino instantly peels off and attaches herself to mama’s right flank; her relatives trail behind as Tsuchi picks up the pace, slicing through water like a boss.

Then, a remarkable moment, one you could miss if you didn’t know what to look for. With a jerk of her head, Tsuchi bites off a piece of the fish she’s holding in her mouth, and lets it float back. Is this what it looks like—Tsuchi rewarding Tofino’s babysitters with a salmon snack?

In the footage, one orca snaps up the salmon in an instant. But there’s not enough for everyone. And that, her aerial observers fear, could be the story of young Tofino’s life.

One orca snaps up the salmon in an instant. But there’s not enough for everyone. And that could be the story of young Tofino’s life.

Southern Resident killer whales, says Cindy Hansen of the nonprofit Orca Network, have huge brains capable of empathy, critical thinking, judgement. For Indigenous Coast Salish peoples like the Lummi, Samish, and Squamish Nations, orcas are literally family, celebrated in naming ceremonies and in stories passed down through generations.

But the charisma of these mammoth salmon hunters reaches even those who’ve never seen one breach, or watched that black-and-white ripple streak beneath the water, as long as a yacht. Orcas make international headlines—as was the case in 2018, when the world watched Tahlequah, another J Pod member, carry her dead calf for 17 days in mourning.

The charisma of these mammoth salmon hunters reaches even those who’ve never seen that black-and-white ripple streak beneath the water, as long as a yacht.

As with humans, orca family bonds last entire lifetimes, from Shachi, Tofino’s great-aunt and one of J Pod’s oldest matriarchs, to its newest surviving additions, two calves born in September 2020, ten months after Tofino—including a little boy, J57, born to Tahlequah.

“The day after J57 was born, the other two pods came in from the ocean for a huge cuddle puddle,” says Hansen. The pods had good reason to celebrate, with three new orcas babies since 2019, after years of miscarriages.

If that sounds tragic, you’re right. Southern Resident orcas are in trouble, plain to any whale watcher now lucky enough to see one. In recent years, some pod members have shown signs of “peanut head”—a deflated dip, behind the blowhole, that means malnourishment. Even more heartbreaking are the infant mortality rates among female Southern Residents, now as high as 69 percent.

At just 75 orcas, the pods currently need at least 500,000 Chinook per year—roughly the same as B.C.’s 2019 combined Chinook catch across commercial, recreational, and First Nations fisheries.

A big reason why, says Hansen, is that they’re starving. And on the surface, the solution sounds simple, too: orcas need more salmon, particularly spring Chinook, the fatty, calorie-rich early returners that sustain these three pods from May through late summer, composing some three-quarters of their total annual diet.

While K and L Pods forage elsewhere in winter—following Columbia and Snake River runs down the Washington Coast, and sometimes much further south—J Pod has traditionally stuck close to the Salish Sea, relying heavily on springers from British Columbia’s Fraser River to refuel after winter.

At just 75 orcas, the pods currently need at least 500,000 Chinook per year—roughly the same as B.C.’s 2019 combined Chinook catch across commercial, recreational, and First Nations fisheries. But we’d need to double that number for orcas to reach sustainable population levels, Hansen says. With hard competition for that fish, from humans and other species, it’s clear that this salmon problem is anything but simple.

For Hansen, who’s lived in thrall to these creatures for the past two decades, we have a moral imperative to work this out. Starting with one place in particular.

“The Fraser River is incredibly important for the orcas. Those are the salmon they should be eating in spring all through summer,” she says. “If orcas are going to have a future, it will be because we’ve recovered salmon throughout their range, including the Fraser.”

From Hansen’s home perch on San Juan Island near the U.S./Canadian border, she’s watched J Pod stick it out, through births and deaths, feasts and now famine.

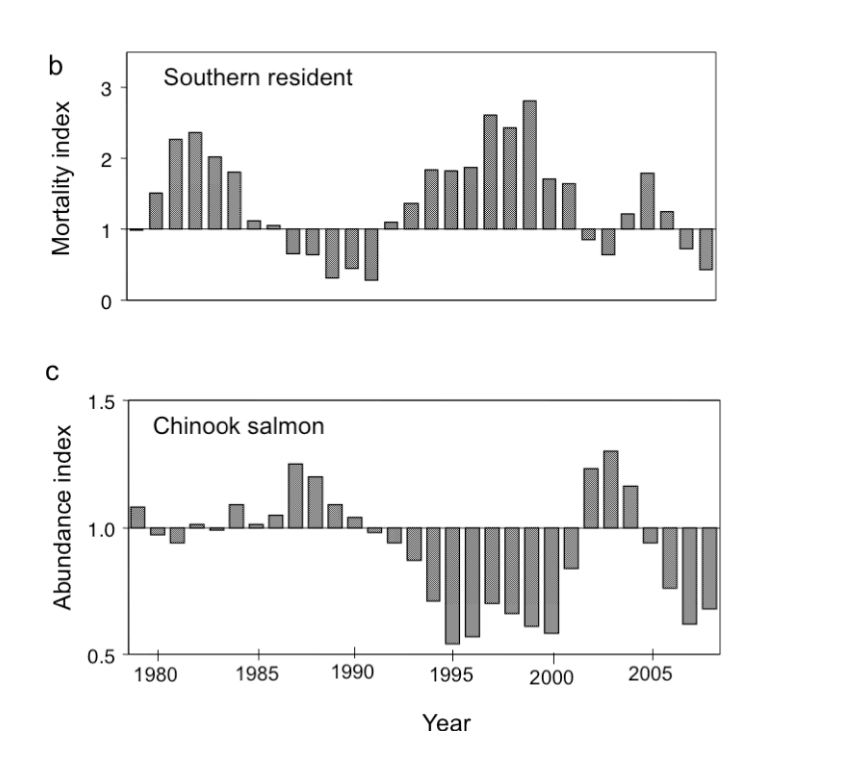

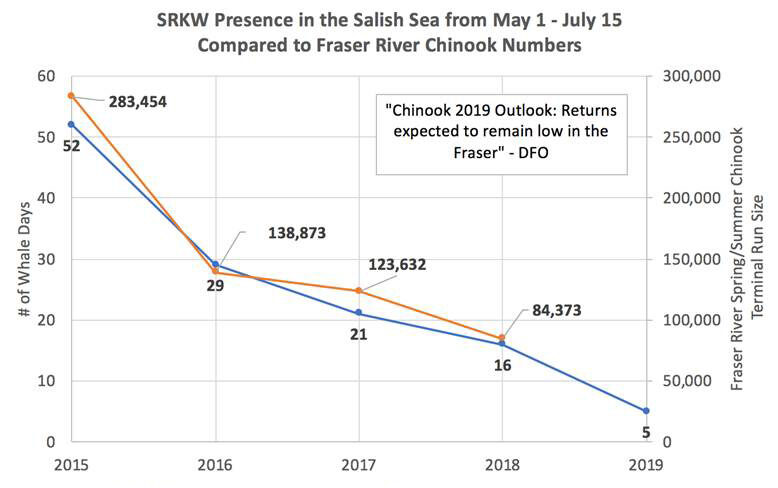

Orcas’ rising mortality rates are tracked by Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans, and the agency’s scientists have mapped an obvious overlap with declining Chinook abundance. (See above bar chart.) For Hansen, the Orca Behavior Institute created an even more personal visual: plummeting salmon runs tracking closely with Salish Sea “whale days,” or sightings. (See above line graph.)

“It’s a correlation, but a strong one,” she says. “To me, it’s very clear why the orcas aren’t here like they were in the past.”

If orcas are going to have a future, it will be because we’ve recovered salmon throughout their range—including the Fraser.”

Marine and river conditions, recent catastrophic landslides, aging tide gates along with predators, pollutants, poaching, and poorly monitored fisheries—ask people why the Fraser’s spring Chinook runs are down, and you’ll get at least as many answers as there are orcas. (And hot debate.)

At the northernmost range for true spring Chinook, the Fraser’s spring run is considered endangered by multiple government entities. Yet it remains unlisted under the Canadian Species At Risk Act (SARA), and thus not fully protected. Greg Taylor, a B.C.-based fisheries consultant and recovery specialist for organizations like SkeenaWild Conservation Trust and Watershed Watch Salmon Society, says that’s still a bridge too far for the Canadian government, which has yet to list any species with commercial and recreational value.

The Canadian government has yet to list any species with commercial and recreational value.

Taylor thinks the government can’t afford to wait. Both spring Chinook escapement and overall abundance have hit historic lows in recent years, prompting grave concern among First Nations, conservationists, and others. In 2019, just 14,500 Fraser spring and summer Chinook reached spawning grounds, well below target, despite a decade of reduced recreational catches and wholesale closures of First Nations fisheries.

Salmon managers still have the chance to recover the Fraser’s spring Chinook. Here, unlike spring runs further south—on the Snake and Columbia Rivers, the Rogue and Klamath-Trinity—the big roadblocks aren’t dams.

Even so, small, incremental decision-making won’t cut it—say, a bit of habitat restoration here, or tide gate repair there. The first big step to save the Fraser’s spring run, Taylor says, is to secure a national SARA listing. It’s a tricky kettle of fish, politically; listing would likely mean even fewer fishing opportunities for humans in short term. Yet the long-term cost of inaction is far greater: the loss of these species, along with our fisheries.

“Right now, we have to get every spring-run fish possible to its spawning grounds,” Taylor says. “We have to have a vision of what we want in terms of Chinook and orcas 50 years from now, and begin to act. That’s only 12 cycles for these salmon, remember.”

The urgency of this moment demands big, bold action. Because what’s at stake isn’t just the survival of one species, or even two. It’s a multitude.

Species protections are just one step. For Taylor, and Hansen, and a growing host of deeply concerned Pacific salmon advocates and conservation scientists, the urgency of this moment demands big, bold action in watersheds from California to Alaska—from tearing down dams to rebuilding habitat, from enforcing fishing regulations to rethinking the very way we fish. That’s because what’s at stake isn’t just the survival of one species, or even two. It’s a multitude.

Salmon are an ancient species, predating ice ages and floods, changing climates and natural catastrophes. Over millions of years of resilient, creative adaptation, wild salmon have evolved into what zoologist Robert Paine called a keystone species: an animal of such critical importance that it threads entire ecosystems. Across the North Pacific, more than 137 species depend on salmon, from grizzlies to fish owls and salamanders.

Over millions of years of resilient, creative adaptation, wild salmon have evolved into a keystone species: an animal of such critical importance that it threads entire ecosystems.

Spring Chinook, historically the biggest, most nutrient-packed, and highest-climbing of all salmon, play an especially vital role in the complex food webs that link oceans to a river’s uppermost reaches. In the Fraser, their carcasses literally feed forests as far east as the Alberta border. Extirpate the river’s springers, and the impacts cascade: trout suffer, along with eagles and other raptors. Grizzly populations contract, collapsing inland predator-prey relationships. And in the Salish Sea, orca populations go hungry.

“You can’t de-link orcas from salmon,” says Greg Taylor. “They have evolved over thousands of years to take advantage of this wonderful food source. Salmon are absolutely core to the survival of Southern Residents.”

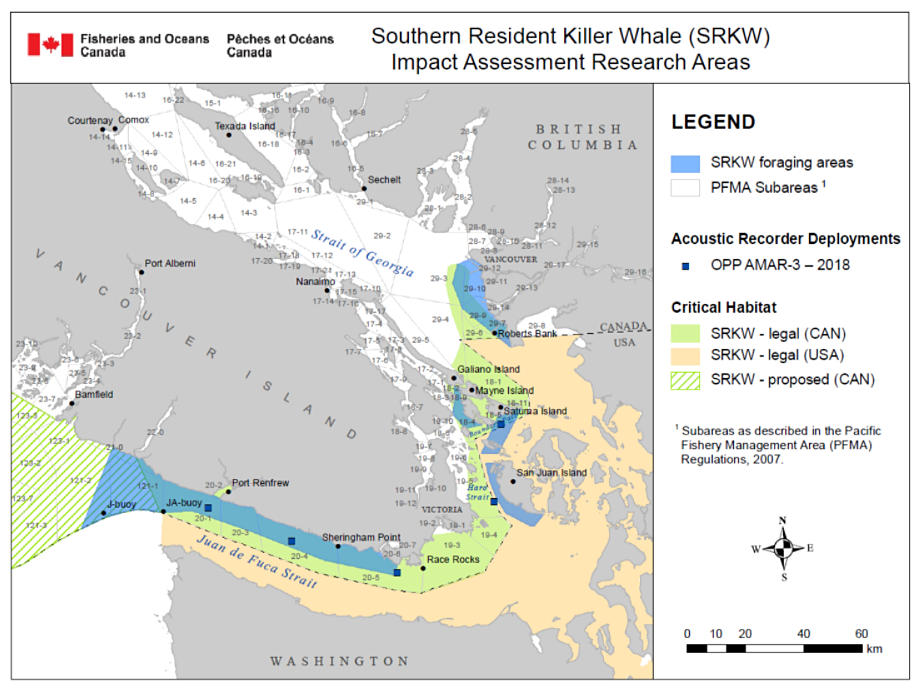

For J Pod, Taylor can make this link explicitly clear. With a map of the Salish Sea in his head, he traces springers’ return route from memory: south along the western edge of Vancouver Island to connect with the Strait of Juan de Fuca, curving north to San Juan Island, westward to Saturna Island, and then meeting the Fraser River just north of the Canada-U.S. border.

“Where do we find the orcas, but in those exact spots,” says Taylor. “And yet, now they’re talking about building a new port right on top of spring salmon habitat at the mouth of the Fraser River!”

He pauses, takes a breath. He’s devoted his whole career to ground-truthing B.C.’s relatively hands-off salmon management approach. At the most basic level, he’s found it wanting.

“If you want a world with orcas,” he continues, “you gotta start by not killing the fish.”

An orca breaching the water’s surface, white belly catching light. A spring Chinook at the river mouth, leaping high, grayish purple back and silver sides. A fisherman in a small boat, scanning the scene through polarized glasses, transfixed.

“Humans are animals, too,” says Wild Salmon Center’s Guido Rahr, a lifelong fly fisherman preaching the gospel of catch-and-release. “Chasing something around in nature is still a part of us. Our bodies, brains, and heart all want that—to be humbled and taught and challenged by a species like salmon, one that we’ve worshipped for millennia.”

As orcas stalk spring Chinook in the ocean, fly fishers hunt them in freshwater, hoping to spot a pod, “like a big, silvery mirage,” land one, and then (if it’s a wild fish) tenderly let it go.

One sunny morning, the air salty near a river mouth on Oregon’s North Coast, he remembers watching a convergence of nature from his small boat. Above, a swirl of cormorants, gulls, and geese. On the water’s surface, the still, bobbing heads of harbor seals. All eyes fixed on a wide, flat tailout, and the nearly imperceptible wake of a pod of bright spring Chinook.

“They weren’t trying to hide, they wanted to be out in the flat,” Rahr says. “They wanted to be where they could outrun the seals, which had probably been chasing them all night.”

With threats on all sides, Rahr watched the springers simply swim through it, beautifully iridescent, swept with star-shaped black spots. These days, he’s content to simply watch a spring Chinook and ponder its mysteries.

Rahr and like-minded fly fishers walk this careful line—catching and releasing, fishing selectively or not at all—because a new balance is called for in these difficult times.

“I went maybe eight days without a strike this year, and that’s completely okay with me,” he says. “Nothing is as interesting as chasing an elusive traveler in my home waters.”

Rahr and like-minded fly fishers walk this careful line—catching and releasing, fishing selectively or not at all—because a new balance is called for in these difficult times. He believes that humans belong in the same food webs that link orcas and salmon, raptors and caddisflies. But he agrees with Taylor and Hansen that we must rethink our role in these systems.

That starts with the outsized impact of marine salmon fisheries, Rahr says. But he extends this challenge to the fly fishing community, where fish can be killed even when catch-and-release is practiced. We can no longer shrug off high incidental mortality rates in recreational fisheries, he says, as simply the cost of doing business. Not when salmon, like orcas, are the red-blinking warning light of an ecosystem in decline.

“Something that every angler knows in his or her heart, is that with the privilege of fishing comes the obligation to protect your home rivers,” Rahr says. “People who worship spring Chinook know this, too. They’re the vanguard: the first to migrate up the river, the first to spawn. And they’re our most important hope.”

Like orcas, humans also evolved alongside spring Chinook over millennia. For Indigenous communities who consider salmon and orcas to be family, the struggle of these species to survive parallels their own communities’ experiences since Western contact.

This empathy can help us. We have a role to play in our home waters, and a responsibility. We must recover spring Chinook, in the Fraser and beyond. That means we must act now, or lose our last chance to save the first salmon.

A SPRING CHINOOK ACTION PLAN:

- Remove the Klamath and Snake River dams

- Empower Indigenous knowledge in salmon management practices

- Increase endangered species protections for spring Chinook across their range

- Improve springers’ access to exclusive spawning habitat apart from Fall Chinook

- Promote the use of selective fishing tools like weirs, wheels, pound nets, and dip nets

- Decrease incidental mortality rates in recreational and commercial fisheries

- Reduce competition from hatchery salmon

Spring Chinook Series | Part I | Part II | Part III | Part IV

Hero Image