In Northern British Columbia, the Taku River Tlingit First Nation is navigating climate change and complex politics—while advancing a bold wild fish strategy.

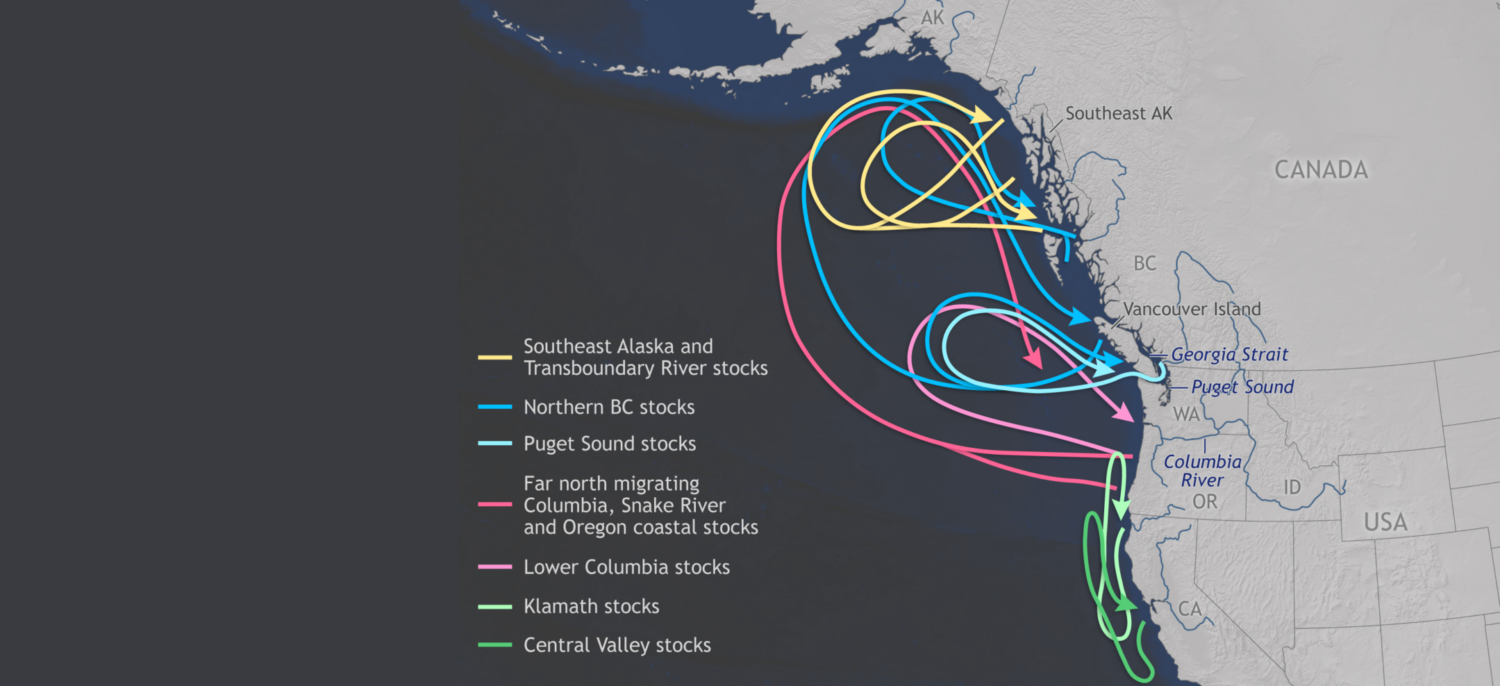

Salmon know no borders. But humans do—and our border politics can have consequences for vulnerable wild fish. Case in point are transboundary salmon rivers like the Taku. Originating in the territorial homelands of the Taku River Tlingit (pronounced KLING-kit) First Nation, high in the boreal forests of British Columbia’s Stikine Plateau, the Taku crosses the Canadian border into Alaska near Juneau before entering Taku Inlet and the Pacific Ocean.

For salmon traveling from freshwater to ocean and back, the invisible lines between jurisdictions bring complex human interventions. For Indigenous salmon communities like the Taku River Tlingit (TRT)—a key Wild Salmon Center partner—transboundary issues are also complex, spanning politics, culture, and climate change.

“Fisheries management on transboundary rivers like the Taku require a great deal of intergovernmental cooperation,” says WSC Senior Watershed Scientist Dr. Will Atlas, who helped to advance our recent partnership agreement with the TRT First Nation. “The experiences and insights of the Taku River Tlingit can help inform how salmon management policies could and should evolve elsewhere in the Pacific.”

One challenge is the current harvest regime for the Taku’s wild fish runs. Alaska’s marine fishing fleets are the first to encounter Taku salmon as they return home to spawn. Currently, the Pacific Salmon Treaty allows for 82 percent of Taku salmon to be harvested in these mixed-stock U.S. fisheries. Yet more than 90 percent of Taku salmon spawning and rearing habitat is upriver in TRT Nation homelands—not Alaska.

“The experiences and insights of the Taku River Tlingit can help inform how salmon management policies could and should evolve elsewhere in the Pacific.”

Wild Salmon Center Senior Watershed Scientist Dr. Will Atlas

But transboundary issues cut both ways. Alaskan salmon advocates point to the legacy of the Tulsequah Chief Mine, located upstream in B.C. For more than 60 years, the former copper, lead, zinc and gold mine has leached acid rock drainage into the Taku watershed just northeast of the river’s border crossing into Alaska—with no proposed plan of action, yet, that satisfies the Alaskan advocates.

Then there are the more universal challenges of a warming planet. The Taku is one of vanishingly few salmon watersheds left on Earth with glacier cover that still surpasses 20 percent. Glacial influence profoundly shapes the Taku’s topography, stream flows, and temperatures, along with where salmon can currently access habitat. But as with glaciers across the North Pacific, the Taku’s ancient ice sheets are melting fast.

The fact that the Taku is changing isn’t lost on the Taku River Tlingit. In response, the community is taking bold new steps to protect Taku salmon from the river’s headwaters to the U.S./Canada border. In 2023, the TRT Nation named 60 percent of the 1.8-million-hectare Taku watershed an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area, declaring this area now off-limits to extractive industries like mining, and asserting the Nation’s primary stewardship role over the watershed.

For Mark Connor, the Nation’s Fisheries Coordinator, this land declaration introduces a new and hopeful chapter in regional governance issues. The B.C. provincial government has yet to formally acknowledge this new protected area, Connor notes—but the Taku River Tlingit aren’t waiting to advance their conservation vision for the region’s wild fish runs.

“TRT is working on resiliency on a couple levels,” Connor says. “When we talk about salmon resilience, part of it is science, but there’s also cultural and organizational resilience: reconnecting the Tlingit people with the land.”

“When we talk about salmon resilience, part of it is science, but there’s also cultural and organizational resilience: reconnecting the Tlingit people with the land.”

Taku River Tlingit First Nation Fisheries Coordinator Mark Connor

Supported in part by The Stronghold Fund, WSC’s impact fund for salmon, the TRT Nation is now working on a basin-wide vulnerability assessment to identify where climate shifts—from glacier retreat to warmer water—are impacting the Taku’s culturally and commercially important populations of sockeye, coho, and Chinook salmon, along with runs of pink and chum salmon. Factoring climate change into fisheries policies is another area in which the Nation’s approach to stewardship holds lessons for the broader salmon community.

“It’s crazy how fast things are happening in the Taku,” says Dr. Jonathan Moore, Director of Simon Fraser University’s Salmon Watersheds Lab and a member of Wild Salmon Center’s Science Advisory Board. Dr. Moore’s work often focuses on how climate change and human land uses impact salmon. He’s one of several scholars now working with the TRT Nation to advance its work on salmon resilience and climate change.

“It’s crazy how fast things are happening in the Taku.”

Simon Fraser University Salmon Watershed Labs Director Dr. Jonathan Moore

“The Taku has no roads, no dams, and very few direct impacts of human development,” Dr. Moore adds. “So as we watch this watershed transform, with new lakes and new floodplain forests, we know that climate change is the driver.”

Climate impacts are already complicating the Nation’s wild fish stewardship, Connor says. In 2018, wildfires merged into a megablaze one watershed south of the Taku in the Stikine watershed: a sobering reminder of the Taku’s own drought-enhanced vulnerability. In 2020, a massive landslide temporarily impeded sections of the Taku mainstem, smothering and scouring salmon habitat. In 2021, record low water flows blocked passage for nearly the entirety of one key returning sockeye population.

“As we watch this watershed transform, with new lakes and new floodplain forests, we know that climate change is the driver.”

Simon Fraser University Salmon Watershed Labs Director Dr. Jonathan Moore

“We’re told that with climate change, we can expect more landslides and these kinds of extreme weather events,” Connor says. “And yet, the Taku remains about as pristine as you’ll find anywhere in this part of Canada. We’re a stronghold, the best of what’s left.”

That assertion aligns with WSC’s stronghold approach, which aims to focus conservation resources on maintaining largely intact rivers systems like the Taku, as our best long-term strategy for protecting wild salmon and steelhead resilience across their range.

“We’re told that we can expect more landslides and these kinds of extreme weather events. And yet, the Taku remains a stronghold, the best of what’s left.”

Taku River Tlingit First Nation Fisheries Coordinator Mark Connor

In the still largely-protected Taku, accelerating glacier retreat is another area that represents new challenges—along with a potential silver lining. According to research from a team of scientists including Dr. Moore and WSC Science Director Dr. Matt Sloat, glacier retreat could open up new spawning and rearing areas for salmon, as long as these lands remain safe from the impacts of future human development.

Connor says that TRT is taking emerging science on glacier retreat seriously, and building the prospect of future salmon habitat into its conservation plans.

“Glacier retreat does have the potential to create new habitat for salmon,” Connor says. “But these are also areas where the mining sector has a lot of interest. These are conversations we should have now. And the more we know about our fish, the better.”

Gathering that knowledge is an ambitious task. The Taku drainage covers roughly 40,000 square kilometers, and its steep, alpine subwatersheds are primarily accessed by helicopter. Tlingit Land Guardians and technicians are now regularly monitoring returning sockeye and Chinook at three weir sites at King Salmon Lake, Kuthai Lake, and the Nakina River. They’re also sampling spawned-out carcasses at a third weir site for genetic sampling, and preparing to capture data on outmigrating smolts at a fourth site on King Salmon Lake.

“Glacier retreat does have the potential to create new habitat for salmon. These are conversations we should have now.”

Taku River Tlingit First Nation Fisheries Coordinator Mark Connor

This information—along with river temperature data from 48 new loggers installed across the watershed—can help TRT better understand where and how wild fish thrive, today and into the future.

From mixed-stock fishing and border politics to mining and climate change, the challenges for Taku salmon are complex—and growing. But fortunately for these cherished wild runs, the TRT First Nation’s proactive and evolving salmon strategy aims to meet this moment.

“Salmon habitat is changing across the Pacific Rim,” Dr. Atlas says. “The Taku River Tlingit and their science partners are helping the world learn how salmon—and humans—can adapt. What we learn in the Taku could help protect wild fish resiliency for decades to come.”

“What we learn in the Taku could help protect wild fish resiliency for decades to come.”

Wild Salmon Center Senior Watershed Scientist Dr. Will Atlas

Hero Image

Hero Image (Home Page Section)